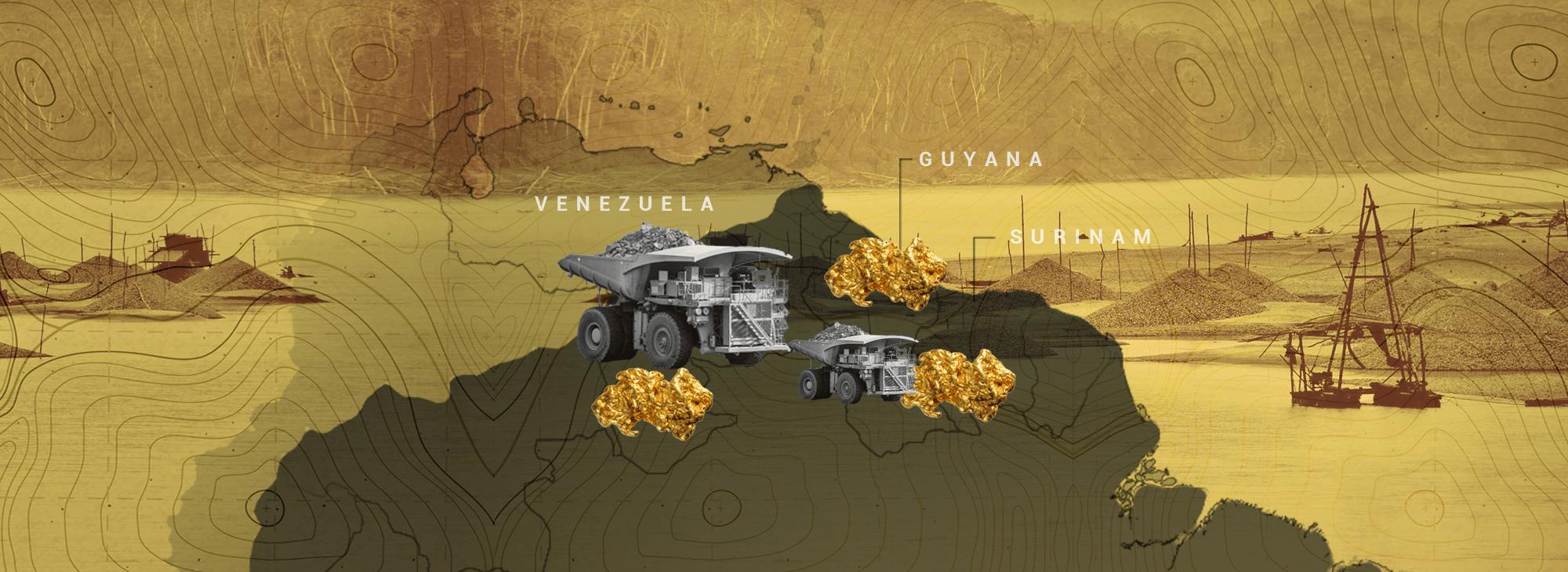

As gold prices have skyrocketed, a boom in mining across the Amazon Basin has flourished, leaving a deep environmental footprint. Illegal mining has become one of the main drivers of deforestation in the Amazon, above all in Venezuela, Guyana, and Suriname. Though it contributes to forest loss in Bolivia and Ecuador as well, it is not the main driver.

*This article is part of a joint investigation by InSight Crime and the Igarapé Institute on how wildlife trafficking, illegal logging, illicit gold mining, and slash-and-burn land clearance are spreading across five Amazonian countries: Ecuador, Venezuela, Bolivia, Guyana, and Suriname. Read the other chapters here or download the full PDF.

There are three forms of mining-driven deforestation in the Amazon Basin: large-scale industrial gold mining, medium-scale mining, and artisanal, small-scale mining (ASGM). The most recent data available from the Referenced Socio-Environmental Information Network (RAISG) shows that there are at least 4,472 illegal mining sites across the region. Some sites cover several square kilometers.

The activity follows three main steps: extraction, transportation, and transformation/commercialization. First, gold is extracted by poorly paid miners, who work in rudimentary conditions. In many cases, they work under the control of NSAGs. Then, the metal is transported onward. It is laundered or “transformed” along the way. The origins of illicit Venezuelan gold are covered up as it is moved through Guyana, Suriname, and Colombia. Eventually, gold and other metals reach international markets, where they are legally sold. In December 2021, a kilogram of gold fetched up to $57,152.

Venezuela

In Venezuela’s southern Amazon region, gold mining is a principal driver of deforestation and a source of biodiversity loss. It is a major criminal economy, underpinned by corruption, the use of violence, and the instrumentalization of local populations by NSAGs. Currently, some 70,000 hectares are affected by illegal mining in the nation’s Amazonian states. These include Bolívar (64,705 hectares), Amazonas (2,356 hectares), and Delta Amacuro (2,169 hectares).

In 2016, mining across the three states faced a turning point when President Nicolás Maduro introduced the Decree of Creation of the National Strategic Development Zone of the Orinoco Mining Arc, which regulates the Orinoco Mining Arc (Arco Minero del Orinoco – AMO). This allowed new mines to be set up. It also encouraged public institutions tied to the regime to get involved in mining.

While considered legal by Venezuela, mining along the AMO is seen as illegal by the United States and allied nations that have sanctioned the Maduro regime. Other countries — particularly those who continue to trade with Venezuela — consider the country’s mining activity as legal. It is also important to note that concepts like “legal” and “illegal” lose all meaning at a domestic level. There are scarce regulations in place to restrict mining in Venezuela. And while some criminal groups operate independently, most involved in mining have ties to the Maduro regime.

Experts from an NGO studying environmental crime in Venezuela revealed that in the Amazon each member of the regime has access to a gold mine, acting as its administrator. They choose which NSAG helps them in overseeing its operation and ensuring its security, according to the experts.

Today, through formal corrupt channels overseen by officials with ties to the Maduro regime and informal channels dominated by NSAGs, gold is extracted, transported/laundered, and sold.

First, gold and coltan are extracted by miners working under the control of NSAGs along the AMO. In Amazonas, ex-FARC mafia are involved in illegal gold mining in the municipalities of Atabapo, Autana, and Atures, according to an expert with a deep knowledge of illegal mining in the state. Dissidents run illegal mining sites alongside gasoline smuggling, the expert added. Coltan, a metallic ore refined for use in electronics, is also mined in Atures, close to the Venezuela-Colombia border. There, members of local communities are employed by dissidents to work as miners. They are often paid in coltan.

Yapacana National Park, located in western Amazonas state, is also targeted by NSAGs. The park is a “natural island in the middle of the jungle, surrounded by rivers and controlled by guerrillas,” according to the experts from an NGO studying environmental crime. “It is a paradise for illegal mining, all controlled by the ex-FARC or Colombia’s National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN),” another mining expert explained.

Illegal mining also occurs at the state’s border with Brazil. Miners in Amazonas control illegal sites located in mountainous areas of Serranía de la Neblina National Park, located close to the border. They use Indigenous communities, maintain alliances with Venezuelan armed forces, and pay bribes in cash or gold to other criminal groups to avoid territorial disputes.

Meanwhile, mining in Bolívar — where the region’s largest mines are concentrated — occurs through two channels. The first is a formal one, where mining cooperatives get permission from the Venezuelan government to extract gold.

The second is directly controlled by NSAGs, who allow mining activity to occur on territories they control in exchange for monthly payments in cash or gold. These groups may also control their own mines. For example, the ELN extorts miners in some cases and pressures local populations to open mines for them in others.

To extract gold, mercury is used to separate tiny particles of gold from sediment. Mercury is smuggled, via plane or boat, to Venezuela from neighboring Guyana. The chemical is smuggled across the Cuyuní River, which separates Guyana and Venezuela. It may also be sent along the coast both countries share, although data on this is sparse, according to a report on the illegal mercury trade by IUNC NL, an environmental organization based in the Netherlands.

Once extracted, gold may be moved “formally” via the Venezuelan Central Bank (Banco Central de Venezuela – BCV). The BCV is the only buyer authorized to purchase Venezuelan gold by the nation’s constitution. The gold is usually sent from the BCV to African countries to be refined. It is then sold in Turkey, Aruba, the United Arab Emirates, and China. However, it is estimated that just one-third of all gold mined in Bolívar moves through the Central Bank. The rest is smuggled out of the country via clandestine routes.

Gold leaving Bolívar and Amazonas is often smuggled through the municipality of Puerto Inírida, in Colombia’s eastern department of Guainía. Another part of the gold is also sent to Brazil, where it is passed off as having been legally produced.

In 2020, Brazil Federal Police discovered a network led by a Lebanese citizen who melted gold in the Venezuelan municipality of Santa Elena de Uairén, on the border with Brazil. From there it was smuggled and sold in Brazil.

Another portion of the gold extracted in the state of Bolívar is transported onward from Manuel Carlos Piar Airport in Puerto Ordaz, a city located in the northern municipality of Caroní. From there, gold and other commodities are flown to the city of Maiquetia, located to the north of Caracas.

The gold is then sent onward from Simon Bolívar International Airport in Caracas to the Caribbean islands of Aruba, Curaçao, and Bonaire, which are used as transit points. According to an investigation by journalist and criminologist Bram Ebus, between 2014 and 2019, some 160 tons of Venezuelan gold were moved via Aruba and Curaçao. However, during a field trip carried out by InSight Crime in November 2021, there was no record of gold seizures in Curaçao. From the Caribbean, the gold may be moved to Europe, from which point it eventually reaches countries such as the United Arab Emirates.

Illegal gold is also smuggled out of Venezuela’s Amazon to neighboring Guyana, according to Dr. Samuel Sittlington, an expert in financial fraud and former British Overseas Advisor to the Special Organised Crime Unit (SOCU) in Guyana. He added that some gold crosses the porous border the two nations share, to be sold to local miners or to third parties. These third parties then pass it off as having been extracted in Guyana to sell it on international markets. Sittlington explained that up to $1 million of gold could be moving across the Venezuela-Guyana border each week. Once there, brokers buy it and then sell the metal on to the Guyana Gold Board, so it can be sold on the legal market, according to Sittlington.

Guyana

After speaking with numerous environmental experts during a visit to Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, InSight Crime was able to see how the country has two approaches to treating the Amazon — approaches that seem irreconcilable. The country has a “green” approach that seeks to conserve the Amazon, but simultaneously, it contrasts this with ever-expanding mining operations that are responsible for almost 90 percent of forest loss.

Gold is the country’s main export. There are six established mining districts in Guyana. These include the Berbice and Rupunini mining districts to the south of the country, and the Potaro, Mazaruni, Cuyuni, and Northwest mining districts in the northwest. Illegal mining — without proper permits — has been detected in protected areas, including the Iwokrama Forest nature reserve and Kaieteur National Park in the center of the country, as well as in the Kanuku Mountains Protected Area (KMPA), close to the southwestern border with Brazil.

Illegal mining operations have also been found in Micobie, along the Potaro River; along Guyana’s northwestern border with Venezuela; along the banks of the Cuyuni river; and west of the Essequibo River.

The Guyana Geology and Mines Commission (GGMC), which administers mining concessions in the country, issues three scales of mining concessions that are categorized by area: small (11 hectares), medium (from 61 to 486 hectares) and large scale (from 202 to 5,180 hectares).

Gold mining licenses in Guyana are cheap, renewed automatically, and concentrated among a small number of people. In many cases, licensed properties are sublet to small- and medium-scale miners for a fee, usually 10 percent of gold mined.

“The large mining blocks don’t mine themselves. They sublet their concessions to small miners,” said Trevor Benn, former commissioner of lands and surveys of Guyana.

However, this implies environmental damage beyond deforestation. Small-scale miners use mercury to extract gold, increasing mercury contamination. These mining operations can also overlap with Amerindian territories, creating confusion and conflict among local communities and gold miners. Some Amerindian communities affected by mining operations are located in Port Kaituna, Mathews Ridge, Arakaka, Mabaruma — all in northern Region One — and other communities scattered around Region Nine, in the south, and Region Four, Region Seven and Region Eight, in the north.

Gold is mostly extracted by Guyanese and Brazilian miners working close to the Venezuelan and Brazilian borders. These miners use excavators to clear land on the banks of rivers and engage in dredging activities. Miners also dig tunnels to extract gold, fleeing the site if authorities get too close. In October of 2020, police shut down three tunnels used for illegal mining in the New River Basin in the South Rupununi region, located in the south of the country. No gold or people were found at the site.

Guyanese gold is commercialized through a state-owned company called the Guyana Gold Board (GGB). The GGB has around 12 licensed agents that are permitted by law to buy, sell, and export gold. These brokers transport and refine the metal. It then makes its way to international markets, above all to Canada, the United Arab Emirates, Belgium, Switzerland, and the United States.

Monitoring mining operations for irregularities in Guyana is a challenge due to a lack of state presence. Janette Bulkan and John Palmer, authors of multiple papers on mining and landlordism in Guyana, claimed that roughly 11 inspectors working for Guyana’s mining authority monitor 9,000 mines across the country. Meanwhile, soldiers deployed to the jungle prefer not to get involved, to avoid potential conflict with Venezuelan criminal actors that operate in the region, according to the International Crisis Group.

Suriname

As in Guyana, it is suspected that Venezuelan gold is also passing through Suriname. But, similarly, Suriname’s Amazon is also marked by legal and illegal mining.

Gold is a major legal export for Suriname. The metal accounted for $2.04 billion of the country’s $2.6 billion total exports in 2019. Its importance to the national economy has risen since the outbreak of the pandemic.

Small-scale mining in Suriname almost always happens without permission. In 2009, only 115 of the tens of thousands of small-scale miners within Suriname operated legally with a mining concession. Obtaining a mining concession is very difficult for small-scale miners who lack political connections. Artisanal and small-scale mining is mainly concentrated along Suriname’s eastern greenstone belt, along the country’s border with French Guiana.

There, illegal gold mining sites have been detected in the border village of Benzdorp and the resort (municipality) of Langatabiki, straddling the Suriname-French Guiana border. Illegal miners also work on the fields around Nieuw Koffiekamp, a village on the northeastern banks of the Brokopondo Reservoir.

Further north in the Brokopondo district, Klaaskreek’s Marooon population — descendants of Africans who fled the colonial Dutch forced labor plantations in Suriname and established independent communities in the interior rainforests — has been involved in illegal mining. This is despite the fact that this territory is home to a concession owned by the IAMGOLD corporation.

The Kriki Negi mining area is another site situated northwest of the Brokopondo reservoir. Meanwhile, incursions by miners have even been reported in the nearby Brownsberg Nature Park. These miners also extract gold from the Marowijne River and the Afobaka Lake along the belt. Clashes between local miners and those from other regions or countries have occurred in several of these areas.

Gold mining also takes place in protected reserves such as the Brownsberg Nature Park (Brownsberg Natuurpark), a national park spanning roughly 12,000 hectares in the northeastern Brokopondo Reservoir. The Foundation for Nature Conservation Suriname (Stichting Natuurbehoud Suriname – STINASU) has repeatedly tried to remove small-scale miners from this reserve. This resulted in miners suing the foundation in 1999, so they could recover confiscated equipment.

After that, the government attempted to work with the miners, under the condition that no weapons or mercury be used, and no poaching take place. However, these measures have been ineffective due to a lack of law enforcement.

SEE ALSO: Destructive Gold Mining Plagues Suriname, French Guiana Border

Most gold is extracted from such zones using high-pressure jets of water to dislodge rock and move sediment. For underground mining operations, miners dig several holes about two meters deep. The area is then cleared of trees and other vegetation. After that, high-pressure syringes remove layers of sand and clay until a gold-bearing layer has been reached. Mud is pumped through a suction hose into a sluice box, where gold particles and minerals are caught. Days or weeks later, the sluice box is “washed” with mercury, binding the gold and separating it from other minerals. Finally, mercury is separated from gold as the amalgam is heated.

The gold is then transported, processed, and laundered. Sometimes the metal is sold at the mining site itself, to be transported onward by a third party for export. This often occurs at the waterfront in the eastern town of Albina.

More commonly, the gold is transported to the nation’s capital city of Paramaribo. En route, checks are rarely made. In the rare case where paperwork is asked for, bribes can be paid.

Once in Paramaribo, there is no need to show any paperwork. Licensed buyers pay miners or third parties in euros or US dollars for gold. These buyers then sell it to domestic goldsmiths or exporters. Most is sent to Switzerland. Otherwise, it is sent to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) or Belgium. In recent years the UAE has been increasing its gold purchases at a faster rate than European countries.

It is important to note that not all gold smuggled out of Suriname is mined in the country. Gold from French Guiana is moved into Suriname via the porous 570-kilometer border both countries share. It is also smuggled to Suriname from neighboring Guyana by plane or via the Lawa River, which separates the two countries.

A Dirty Business: Criminal Networks and NSAGs Fuel Illegal Mining

A range of actors fuel gold mining operations. Those who profit most from illegal gold often never visit mining sites. Instead, they rely on well-placed connections, corruption, and workers short of economic alternatives. Actors involved in the activity fall into three broad categories: entrepreneurial criminal networks, NSAGs, and cheap labor.

Entrepreneurial Criminal Networks

Some of the main actors driving illegal mining are criminal entrepreneurs, or leaders of criminal networks. They may be political or economic elites who have the financial capacity to buy high-cost machinery. They often have contact with NSAGs operating in mining hubs. These entrepreneurs direct and initiate operations. They hire local miners and operatives, and they oversee the establishment of new mines.

These networks rely on the work of intermediary criminal entrepreneurs to move gold and cover up its illicit origins. The more the metal changes hands, the better.

Brokers working for or with criminal networks grease the wheels of this supply chain. They buy and sell illegal gold and may also work in the legal trade. In Guyana, brokers sell refined gold bars to traders who do not question the origin of the metal. Similarly, in Suriname, merchants in Paramaribo buy the gold without questioning its origin.

These networks require a wide geographical reach to feed international markets. Their leaders and financial backers may be based far from the illegal mining sites they exploit. In Suriname, Chinese gold merchants working in the nation’s capital also reportedly send a large share of the gold they buy back to China.

Otherwise, well-placed exporters that have ties to foreign markets are relied upon. In Suriname, exporters make deals with jewelers and gold traders based in Dubai, Europe, and the United States, according to a report released by World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Prior to shipment, exporters must show their licenses and register the amount to be transported with the nation’s Currency Commission.

Although exporters are legally obliged to buy gold from the Central Bank to send it abroad, in practice this does not happen.

It is interesting to note that female intermediaries with indirect ties to these networks play a greater role in the trade once the gold has been extracted. According to Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt, an investigator at the Australian National University, Surinamese women in the mining sector are traditionally associated with tasks like transporting and processing, so men can continue to work on site.

Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs)

In Venezuela, NSAGs control mining sites and gold routes. They are predominantly involved in the extraction phase. They collect extortion fees from small-scale miners, often with the blessing of corrupt politicians and authorities. NSAGs may also be paid in money or gold to look after mines belonging to large criminal networks. Some NSAGs now run mines themselves.

In Venezuela, NSAGs have largely shifted from extorting miners in its Amazon region to exercising direct control over illegal mines.

Venezuelan criminal gangs dedicated to illegal mining — known as “sindicatos” or mining “megagangs” — have long profited from the illicit activity. Although some of these groups, including Johan Petrica’s Megagang and the El Perú Syndicate (Sindicato de El Perú), are involved in other illegal activities such as micro-trafficking, their main source of income is illegal mining.

These groups typically have over 100 members. They extort artisanal miners and oversee mining operations in the state of Bolívar. In Bolívar, alliances have been created between local politicians and these groups.

The Johan Petrica Megabanda — the mega-gang led by Yohan José Romero, alias “Johan Petrica” –operates in the mines of Las Claritas, in the Sifontes municipality, located in Bolívar. Like other local mining gangs, its modus operandi centers around the organization and “taxation” of illegal gold extraction, processing, and trafficking.

The Tren de Guayana also operates in the state. Previously, the group used political contacts to move into illegal mining, eventually controlling mines in the municipalities of Roscio and El Callao in eastern Bolívar. Its modus operandi is to “tax” informal gold extraction and processing. Today, the group has lost political protection. However, it still uses corruption to its advantage, with high-ranking members able to evade prison sentences.

The El Perú Syndicate — an NSAG based around the mines of El Perú, in the El Callao municipality of Bolívar — operates differently. Like other local mining gangs, its modus operandi is based on the organization and “taxation” of illegal gold mining and processing. However, it is the only surviving mining gang in Bolívar that operates without any kind of governmental support.

Since 2016, a number of other NSAGs have involved themselves in mining across Venezuela’s Amazon. Sites owned by the Maduro regime are overseen by NSAGs on the ground. Otherwise, NSAGs control their own mines. In the state of Amazonas, the Acacio Medina Front, an NSAG made up of ex-FARC dissidents led by Miguel Díaz Sanmartín, alias “Julian Chollo,” is present. Julian Chollo oversees criminal gold operations in Yapacana National Park (Cerro Yapacana), a major hub for illegal mining in the Orinoco-Amazon region.

The ELN Daniel Pérez Carrero Front, led by Wilmer Albeiro Galindo, alias “Alex Bonito,” has also been increasingly involved in the activity since 2016.

Venezuelan NSAGs have moved into illegal mining in Guyana. Sindicatos charge miners working along Guyanese borderlands a fee in exchange for protection. Boats carrying supplies to Guyanese mines must pass checkpoints controlled by the ELN, sindicatos, and Venezuelan security forces. Each step of the way, extortion payments are charged at gunpoint. Guyanese miners conduct their operations in the shadow of these armed groups.

Legal enterprises

A number of mining export companies have been accused of trading illegal Venezuelan gold.

El Dorado Trading is one of Guyana’s main licensed gold exporters. It sells gold to international refineries in Canada and Switzerland. In late 2020, the Guyana Gold Board (GGB) investigated allegations that El Dorado had been buying gold from Venezuelan criminal groups. The company denied these accusations. However, the Royal Canadian Mint (RCM) announced it would stop purchasing gold from El Dorado until further notice.

Similarly, high-profile international refineries and other legal enterprises, such as transport companies, have been caught buying illegal Venezuelan gold. As InSight Crime reported in June 2021, the owner of South Florida transport company Transvalue was accused of “facilitating a $140 million transnational illicit gold smuggling operation.” An unsealed affidavit suggested the gold was likely being “illegally mined and smuggled out of Venezuela.” On arrival in the United States, Transvalue moved the gold to a Florida refinery belonging to NTR Metals — a Miami-based subsidiary of Elemetal, one of the largest gold trading companies in the United States. It was eventually purchased with “clean” money by associates who earned commissions by procuring the illicit product for NTR Metals, according to the United States Department of Justice (DOJ).

Meanwhile, some refineries have been accused of money and gold laundering. This has been most evident in the case of Suriname, whose government-backed Kaloti Suriname Mint House (KSMH) has faced allegations of money laundering and buying gold from conflict areas for years.

The KSMH is a joint venture between Dubai’s Kaloti Jewelry Group, the government of Suriname, and Surinamese gold traders. According to government officials, the KSMH was founded in 2014 to purify all gold that Suriname exports and boost the nation’s gold industry. It also sought to extend services to other countries in the region. Former President Desi Bouterse joined Kaloti Chairman Munir Kaloti in a press release stating that KSMH would transform Suriname into a “center of excellence for the region’s gold and precious metals industry.” According to an investigation by the Center for a Secure Free Society, a security think tank, Bouterse continued to support the refinery during his time in power.

After setting up operations in 2015, the KSMH was labeled as a “risk” for mixing proceeds from gold and drugs. In a 2017 report by the Center for a Secure and Free Society, the refinery was labeled as a “fictitious project.” Having conducted interviews with gold dealers and visited the site itself, the organization “confirmed that there was no refinery and no gold refining taking place at the KSMH.” As a result, the government could certify the exports of any amount of gold, real and fictitious, “from a refinery that exists only on paper,” according to the report. It concluded that, for a price, transnational organized crime groups could use state certification “to launder almost unlimited amounts of cash as if it were gold.” Security consultant Douglas Farah added that the refinery allegedly certified non-existent exports and gold coming from Venezuela as originating from Suriname. The Surinamese government joined Kaloti in denying these allegations.

Several experts and journalists consulted by InSight Crime who have followed Suriname’s mining sector closely but preferred to remain anonymous maintained that KSMH is likely involved in gold laundering. Previous investigations into the KSMH support this.

A report by journalist and criminologist Bram Ebus made some interesting conclusions. Ebus wrote that Suriname’s “government failed to promote gold imports from its neighbors and the project has yet to turn a profit.” According to the refinery’s managing director, Ryan Tjon, the KSMH processed between 15,000 and 20,000 kilograms of gold in 2019. Tjon admitted that gold trafficking is an issue, but told Bram Ebus that “we are not the ones, the agency, to investigate where the gold actually comes from. We are not a police officer.” Tjon concluded that if an exporter says it is Surinamese gold, the KSMH takes it on good faith.

In 2021, a Surinamese journalist visited the KSMH, describing it as an “abandoned government office,” with an empty parking lot and closed shutters. Three soldiers reportedly guard the building permanently from a corner watchtower. One of them told the journalist he had never entered the building and did not know what was going on inside. However, he did confirm that the building still belongs to Kaloti. Today, cars drive in and out every day, but the windows never open nor is there any light, according to a local resident.

Bouterse’s successor, President Chan Santokhi, has ordered an investigation into the refinery’s role in Suriname.

Cheap Labor

Local people or migrants searching for economic opportunities are usually hired as miners to extract gold. They sit at the bottom of the chain, receiving the lowest financial reward from the activity. These miners live in makeshift camps and work in perilous conditions. They may extract gold, coltan, or copper under the close watch of NSAGs or members of criminal networks. While these miners may act illegally, they can hardly be classed as hardened criminals.

In the likes of Venezuela, migrants from other regions or countries invade protected territories to work as miners. Meanwhile, Brazilian small-scale miners, or “garimpeiros,” have also migrated across the Amazon in search of gold. Most small-scale miners in Suriname are Brazilian migrants who send money obtained from gold mining back home.

Chinese and Brazilian migrants also work as miners in both Guyana and Suriname.

Chinese investment in Guyana’s gold mining sector has allegedly brought with it private, small-scale operations that operate under varying levels of legality. Meanwhile, Suriname’s community of Chinese migrants is largely ignored by law enforcement, despite the alleged involvement of some individuals in illegal mining. According to Dr. Evan Ellis, an expert on Chinese criminal groups in Latin America, “the level of penetration by the SDF [Suriname Defense Force] and by the Surinamese police is just about zero in these Chinese communities.” These actors reportedly operate close to gold mining areas within Suriname’s interior, such as the eastern border city of Albina.

Whether local people or migrants, miners often live and work in dangerous and hardscrabble conditions. In Venezuela, they work under the control of NSAGs. There, Indigenous people and temporary migrants from other states extract gold to survive economically. In the face of the nation’s ongoing socio-political, economic crisis, many have no choice but to mine with the approval of sindicatos. However, they face constant security risks. If they steal, their hands may be cut off. Miners have also been massacred in the nation’s Amazon region.

*Luisa Acosta, Nienke Laan, Julian Lovregio, and Scott Mistler-Ferguson contributed to the reporting for this article.

InSight Crime has partnered with the Igarapé Institute – an independent think tank headquartered in Brazil, that focuses on emerging development, security and climate issues – to trace the environmental crimes and criminal actors driving deforestation across the Amazon. See the investigations.