Henry Holguín looked out from the empty second-floor balcony of a small restaurant in La Bayadera, a busy industrial neighborhood in the city of Medellín.

“This was a ‘red zone.’ It was wild … You couldn’t even sell a joint here without my authorization,” Holguín remembered with satisfaction.

At first glance, Holguín, 54, appears to be an ordinary person. But a scar between his eyebrows, a reminder of a confrontation with a policeman during his years as an actor in Medellín’s urban conflict, betrays the highs and lows that have led him to where he is now.

Holguín was the leader of a Medellín gang in the mid-1980s, a time when the city’s underworld was growing rapidly in both scale and complexity. But today, 40 years after he first bought a gun and created an armed group to defend himself from neighborhood criminals, Holguín coordinates the Sinergia movement, the civilian spokespeople for one of the criminal gangs in the Medellín metropolitan area that is participating in President Gustavo Petro’s flagship policy of “Total Peace.”

Total Peace is the most ambitious peace process ever attempted in Colombia. To carry it out, the government is seeking simultaneous negotiations with more than 20 armed groups representing the different faces of Colombia’s criminal world: guerrilla insurgencies, drug trafficking armies, and urban gangs.

In doing so, the Petro administration is seeking not only to demobilize specific groups but also to break the cycle of generations of conflict in Colombia, where every time the state has eliminated a criminal actor — whether by persecution or negotiation — a new generation of groups has emerged to take its place.

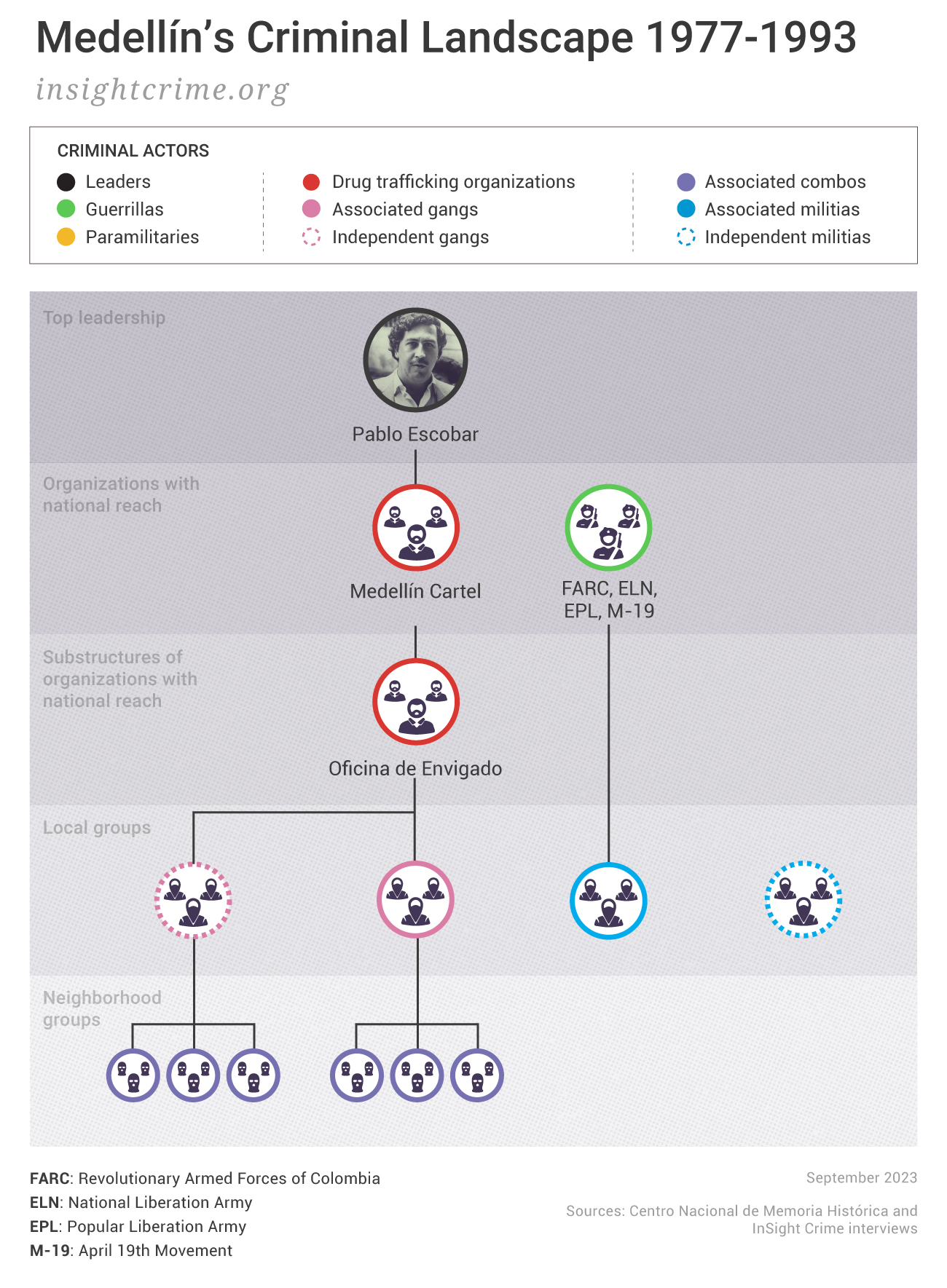

Medellín and other municipalities in the Aburrá Valley in the department of Antioquia have long been a microcosm of the country’s endless violence. The city has been the scene of events that have defined entire eras, from the fall of the first cocaine kingpin, Pablo Escobar, to the first paramilitary demobilization. But each time, far from undermining organized crime, these scenarios have driven criminal evolutions that have strengthened organized crime’s control over the city.

Today, the city’s underworld is complex and multi-layered. Although it is fragmented and leaderless, it is deeply entrenched and has enormous power over the city’s population and its institutions. It may now represent the greatest challenge facing the Total Peace negotiators.

Many doubt their chances of success. But Holguín, who has not only witnessed but also participated in this criminal history, says he is living proof that change is possible.

Who Fills the Gaps of an Absent State?

Holguín grew up in the Popular 2 neighborhood on the northeastern slope of the mountains that surround Medellín. The neighborhood began as an informal settlement built by its own inhabitants, most of them migrants who had fled rural areas where a war was raging between the state and Marxist guerrilla groups formed in the 1960s.

In the 1980s, some of these guerrillas took their armed and political activities to Medellín and other urban areas. This marked the moment when the war arrived to Colombia’s cities, laying the groundwork for an urban conflict that continues today. According to Holguín, it was also the moment when he, at just over 10 years old, was introduced to arms.

It happened one day in the early 1980s, when a group of armed men and women, their faces covered, entered his classroom. They identified themselves as members of the Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación – EPL), a guerrilla group that had emerged in 1967 as the armed wing of the Marxist-Leninist Colombian Communist Party (Partido Comunista Colombiano Marxista Leninista – PCC-ML).

At the school, the guerrillas invited the children to a meeting in a house in the neighborhood. Holguín attended. There, he held a gun for the first time as he listened attentively to the guerrillas’ speech.

“They talked about schools, about how they wanted development for the neighborhood,” Holguín recalled. “I felt that with them we could achieve less hunger and less suffering in the community.”

At that young age, Holguín wanted to be a guerrilla. But at the same time, he was attracted to another armed actor operating in his neighborhood: a gang of thieves, who robbed downtown jewelry stores and divided the loot among families in the community.

“I began this internal debate, because on the one hand I saw the weapons of the guerrillas, with their ideals and discourse in favor of our people. On the other hand, I saw the weapons in the hands of these others, who had stolen gold and were sharing that wealth with the neighborhood,” said Holguín.

As a child, Holguín understood something that 40 years later remains one of the main obstacles to achieving peace in Medellín: the sense among many inhabitants of marginalized neighborhoods that the state is not there for them and that those who fill the vacuum are those who wield arms illegally.

Holguín said he joined the EPL’s revolutionary youth movement. But he was expelled shortly after for planning the robbery of a jewelry store. He was accused of being a “common criminal,” words that to this day are chiseled into his memory.

Groups Change, but Weapons Remain

The EPL did not last long in the neighborhood. On August 23, 1984, the guerrillas signed a ceasefire agreement with the government, but this broke down just a month later. For 10 days, there was fighting between the EPL and state forces, Holguín remembered. Afterwards, the guerrillas abandoned the neighborhood.

“The guerrillas — those who had political ideology, those who were capable of exercising discipline — were leaving the neighborhood, and what were we left with? The weapons. In whose hands? In the hands of those recently recruited by the guerrillas,” reflected Holguín.

Following the guerrillas’ departure, a criminal group called Los Chorrillos emerged in the neighborhood. Some of its members had been with the insurgents, and they had kept their weapons after the guerrillas left. According to Holguín, they spread fear among the population, committing robberies, threats, murders, and sexual abuse.

One day that year, Holguín remembers, he went to visit his girlfriend. They were sitting outside the house when the leader of Los Chorrillos arrived.

“You’re looking fine, one of these days I’ll steal you away,” Holguín recalled the man saying to his girlfriend. The brief encounter left Holguín fearful that the leader of Los Chorrillos would assault his partner.

He decided to join two men from the neighborhood, an ex-convict, and a policeman, to declare war on Los Chorrillos, Holguín said. As there were only three of them and they had no weapons, he pawned his motorcycle and bought two revolvers.

One of his companions was in charge of assassinating the leader of Los Chorrillos. After they had killed the leader, they targeted other members of the gang. With each death, Holguín and his small group gained power.

According to Holguín, his burgeoning gang enjoyed the support of the community.

“People started to help us so we could grow militarily. The community [loved] us because [we were] from the community, because we became the authorities, because the community was calm now,” he said. “At that time, we saw ourselves as the good guys in the movie, and we were going to war.”

Gunning and Running

By wiping out Los Chorrillos, Holguín and his small group consolidated themselves as the dominant armed power in the neighborhood. But what began as an act of self-defense turned them into the main victimizers in the area.

Similar dynamics were occurring in other poor neighborhoods of Medellín, where numerous gangs were gaining a foothold. These groups began to serve a larger criminal power: drug trafficking.

SEE ALSO: Profile of Pablo Escobar

By this time, Pablo Escobar and his Medellín Cartel were driving a cocaine boom that would change the face of war in Colombia forever. Drug trafficking became the point of convergence between organized crime and the country’s political and social conflicts.

In Medellín, gangs such as Holguín’s and smaller neighborhood gangs known as combos began to serve as an armed wing for the cartel, and a new figure emerged: the sicarios, young men on motorcycles who killed for money.

Holguín said he committed his first contract killing when he was not yet 17 years old.

“I earned 400,000 pesos” — equivalent to US$4,400 today — Holguín recalled. “At that time, that was a fortune.”

Towards the end of the 1980s, Holguín was invited to join the military wing of the Medellín Cartel.

“It was the highest status for criminals here,” he said.

The invitation came from two brothers known as “Los Picapiedra” (The Flintstones), lieutenants of El Limón, Escobar’s right-hand man. The pair had links to the security and intelligence services, according to Holguín.

SEE ALSO: Profile of la Oficina de Envigado

Holguín accepted. Becoming part of the cartel would give him and his gang easier access to weapons and money and help them gain more territorial power.

At the same time Holguín was working for the Medellín Cartel, a new generation of armed groups known as the militias arrived in the Popular 2 neighborhood. These groups emerged in the late 1980s after the guerrillas had withdrawn from Medellín. They were motivated by a leftist discourse and sought to counteract the rise of gangs in the city, calling for the restoration of order and security through the persecution of actors they considered undesirable, such as thieves and drug users. Some militias were close to the guerrillas, while others remained independent.

The neighborhood militias invited Holguín to join forces and work together, but he refused, because, he said, he did not agree with the motivations behind the murders they committed.

“They killed youths just for smoking a marijuana cigarette,” Holguín said.

This led to a strained relationship between Holguín and militia members in his neighborhood. Then, on December 31, 1989, Holguín said he discovered that a militia leader had destroyed his parents’ house to sell the materials to pay for the militias’ New Year’s Eve parties.

The dispute over the house was confirmed to InSight Crime by a resident of the neighborhood, although according to the source, Holguín had allowed the militia to take items from the house, which had been affected by geological damage. Conflict arose after they also took valuable materials that Holguín had not said they could have.

Furious, Holguín confronted the militia leader, killing him in the confrontation.

Relations with the Medellín Cartel also deteriorated. In the early 1990s, Holguín said, he discovered that Los Picapiedra were stealing money from him from the contract killings they committed together, and he decided to confront them.

“I’d rather steal watches with my friends than millions of dollars with a bunch of crooked people,” he remembered telling them. “That did not go down well, and they declared me a ‘military objective.’”

According to Holguín, he had to leave town. He moved to Pereira, a city south of Medellín, but was captured on his arrival. Holguín says he was charged with being part of the cartel and the murder of the militia leader. InSight Crime contacted the courts to verify his account, but was unable to obtain access to the case file.

The Reorganization of Power

Holguín, who by this time was 22 years old, was sentenced to 17 years in prison, he said.

“I was a kid and I thought the world was ending for me,” he remembered.

While he was in prison, the underworld in Medellín was about to change forever. In December 1993, Pablo Escobar was killed by an elite police unit known as the Search Bloc with the alleged support of the People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar (Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar – PEPES), a group of the capo’s former associates who joined forces to track him down.

But for Holguín, the biggest change came a few months later, in May 1994, when the Popular Militias of the People and for the People (MPPP), the Independent Militias of the Aburrá Valley and the Independent Militias of Medellín demobilized after several months of negotiations with national, departmental, and local governments. This was the first negotiation process between armed groups and institutions to address the urban conflict in Medellín, but some of its failures continue to haunt the current peace negotiations.

The agreement reached by the militias with the government saw 843 militia members receive benefits in exchange for disarming and confessing to certain crimes. As part of the process, demobilized militia members were permitted to carry out private security work through a body called the Security and Community Services Cooperative (Cooperativa de Seguridad y Servicios Comunitarios – Coosercom), which received a two-year contract with the government.

But this led to other problems. The civilian population began to denounce abuses of power committed by the ex-militia members in Coosercom. Instead of leading to a decrease in violence in the city, Coosercom was perpetuating the practice of private justice at the hands of civilians.

Gangs confronted Coosercom in different neighborhoods throughout the city. In the midst of this conflict, Holguín said, he was released from prison in 1994 after a judge ruled the murder of the militia leader to be legitimate self-defense. InSight Crime was unable to obtain the court ruling to verify his account.

Holguín returned to arms and joined the fight against the former militias.

But then came a day in April 1995 that would change everything for Holguín. He was invited as an observer to a dialogue process between the remnants of the militias and the gangs, mediated by civil society and the mayor’s office of Medellín. He agreed to attend, but with an ulterior motive.

“I didn’t believe in peace; I went with double standards because I wanted to identify some enemies from the militias so I could later kill them.” he confessed.

However, his perspective changed the moment he heard a militia leader talk about his dream for the neighborhood. It was the same dream that Holguín and some of the gang leaders shared: a neighborhood where state neglect was not the norm, and where children could grow up safely.

“Our enemy was not the militias. [The enemy was] that loneliness we lived with, that abandonment in the peripheries of the city, where the only thing we knew of the state was the military boot,” said Holguín.

From there, the gangs and Coosercom agreed to a non-aggression pact to put an end to the confrontation between the two sides. The process would be a turning point in Holguín’s life.

“We sat down and we looked at each other knowing that, although we were enemies, we could reach an agreement,” said Holguín.

Although the Medellín mayor’s office participated in the process, there was limited support when it came to creating new opportunities for the young people who were part of the pacts.

“The agreements [were] a pact for life. They were the first aid. But then the state had to invest to make that pact stable. The state did not get to that second part,” an academic who accompanied the process at the time, who preferred not to be identified for security reasons, told InSight Crime.

What happened next would become an Achilles’ heel of Colombia’s peace processes, both in Medellín and in other parts of the country, and stands as a warning from the past for today’s Total Peace plans. In the absence of state support to continue the processes, gang leaders turned to what they knew best to keep the pacts afloat: the money they received from crime.

According to Holguín, to prevent the youths from violating the pacts, the leaders used the criminal income they received to create legal businesses where the youths participating in the process could work.

Multiple sources with knowledge of these pacts in Medellín neighborhoods in the 1990s confirmed to InSight Crime the use of illicit funds to finance microenterprises and other projects.

“We had the kids already engaged in a process, telling them not to steal, not to kill, to collaborate,” Holguín explained. “At the very least we had to give those boys food.”

But according to Holguín, there was another beneficiary of the group’s criminal revenues who was not willing to give up his cut: a police sergeant who received a percentage of the criminal revenues. Holguín claimed he asked the officer to lower the amount he was paid in order to have more resources for the legal businesses.

“No, you are not going to make peace with what is mine. If on Saturday you don’t send me anything, I know who you are and you will have to choose: Bellavista [prison] or the cemetery,” Holguín recalled the policeman saying.

Holguín claimed he decided not to pay him and, as a result, the corrupt official declared him a “military objective.”

One day in April 1996, Holguín was driving a pickup truck through a neighborhood in northeastern Medellín when four bullets hit his car. The bullets came from the same policeman who had threatened him, according to Holguín.

They began to fight. Holguín gained control of the policeman’s submachine gun. He shot him in the leg, he said, and ran to the second floor of a nearby house that served as a safe house.

After a few minutes, Holguín was captured. Unknown to him, the policeman had died from the bullet wounds.

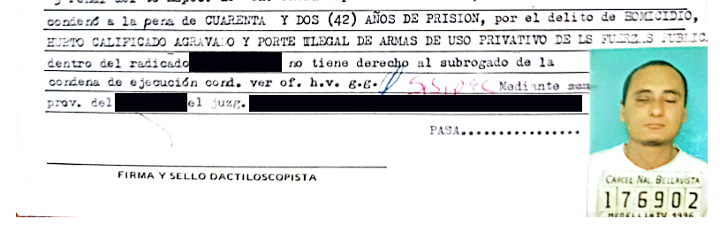

InSight Crime obtained the court file of the case, which confirmed the fight with the officer. However, the police offered a different version of events as to why the confrontation took place. In the file, the police claimed Holguín and his companion were escaping after committing a robbery at an office in a western Medellín neighborhood when the police patrol identified them. According to the police, it was because of this robbery, and not because of a personal dispute, that Holguín was stopped by the sergeant.

From Hitman to Peacemaker

Holguín was sent to Bellavista prison, in the municipality of Bello, near Medellín. He remembered how the first night he cried, knowing that he could spend between 40 and 60 years in prison. He spent his 27th birthday behind bars.

The first year, he spent his days selling breakfasts and working out. Outside of the prison, the pacts began to crack. According to Holguín, the main reason they fell apart was that little by little the gang leaders who had used their leadership to nurture the pacts were being captured.

In 1997, the Medellín mayor’s office brought Holguín and other Bellavista inmates together to mediate from inside the prisons so that the processes would continue in the neighborhoods. Holguín, together with other prisoners, worked on a proposal that sought to put an end to the conflicts. Their project was approved in August of that year.

However, the initiative came under fire because it did not resolve the structural issues fueling the cycles of violence. Instead, the institutional framework allowed the armed actors inside and outside the prison to maintain their criminal power over different neighborhoods of the city, leading to a tacit relationship between the city’s organized crime and its institutions, which continues to be one of the main challenges facing negotiators in the Total Peace process. The rates of violence became the criminal groups’ bargaining chip, which they could use to exert pressure on the authorities and ensure they could continue receiving their illegal income.

Holguín described how, despite being recognized as a leader of the prison process, he continued to receive illegal money from outside of prison. But he began to feel conflicted, especially as he became more religious during his time in prison, and eventually he decided to hand over his income. His subordinates tried to dissuade him, calling him naïve and saying that nothing would change on the street. But, Holguín said, he stood firm.

“I need to take the first step and have things change in me, and be a real peace commissioner, as people are saying,” he remembered telling them.

During the Bellavista process, more than 50 non-aggression pacts were made in Medellín neighborhoods, according to Holguín.

The Bellavista process was part of a broader series of pacts between gangs that had been going on since 1995. By 1999, there had been 160 mediation processes or pacts between armed groups in the city, including gangs, combos and militias, as reported by the newspaper El Colombiano at the time. Approximately 3,000 people from these groups were part of these processes.

“At that time, we were all very happy, [there was] a lot of hope,” Holguín recalled.

However, that happiness was short-lived. By that time, a new armed actor was entering the criminal scene in Medellín, initiating a new cycle of violence in the city that would leave the city’s organized crime more complex, fragmented, and leaderless — the scenario faced by Total Peace today.

New Cycles of Violence: Paramilitarism Takes Over the City

While Henry Holguín was trying to break the cycle of Medellín’s gang war from Bellavista prison, Colombia’s conflict was entering a new, even more brutal phase, as right-wing paramilitary groups spread across the country.

Some were politically motivated to eliminate leftist guerrillas, but others were simply private armies of drug traffickers hiding behind a counterinsurgency facade.

The gap between Colombia’s political conflict and organized crime continued to close, moving towards the situation currently facing Total Peace, where the two sides are almost impossible to separate.

Paramilitaries arrived in Medellín at the end of 1998 when an organization known as the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC) sent one of its units, the Bloque Metro, to the city to eliminate leftist militias.

Following in the footsteps of the guerrillas and the drug traffickers, the paramilitaries sought recruits among the gangs of Medellín’s marginalized neighborhoods, putting them in contact with gang bosses. And in doing so, they ran up against Holguín and his dreams of peace.

It was not long before Holguín received a call from the Bloque Metro trying to convince him to support their cause.

According to Holguín, representatives of the paramilitaries demanded that he hand over more than 3,000 youths who were participating in the peace process he was leading from the Bellavista prison. The paramilitaries wanted to add these youths to their ranks, he said.

Holguín said that he had already rejected these requests on two occasions, but he received one more call. One day in 2001, paramilitary delegates in prison handed him a telephone. When Holguín picked up, he heard the hoarse voice of Carlos Castaño, then the top commander of the AUC and one of the most notorious figures in Colombia’s long and bloody history.

“I got really scared because it was a time of many massacres and a lot of things,” said Holguín. “I started to cry and I told him, ‘I work for peace. Don’t worry. I’ll never let them become guerrillas, and I won’t let them become paramilitaries either. I’m neutral.'”

Castaño’s words were blunt. “Neutral? Who told you that a car in neutral drives?” Holguín remembers him saying before he hung up the phone.

Holguín recalled the conversation he had the following day, when one of the paramilitaries’ men demanded he hand over his cell phone and asked him if they had reached an agreement.

“You know what?” Holguín told him. “When the militias came to take the city, you didn’t exist. And now that we have the city, you want to come in. If you want to recruit those boys, recruit them. But not me. I won’t hand over the process to you. And I’m never going to put my leadership in favor of you recruiting the boys.”

It is impossible to prove whether it was due to his refusal to join the paramilitary project, but shortly after his rejection of their overtures, Holguín was transferred to a prison more than 500 kilometers from Medellín.

From there, he could not prevent the paramilitaries from recruiting many of the young people who participated in the process led from Bellavista.

“I felt the pain of feeling betrayed, of knowing that this dream of peace and coexistence had been cut short,” Holguín said.

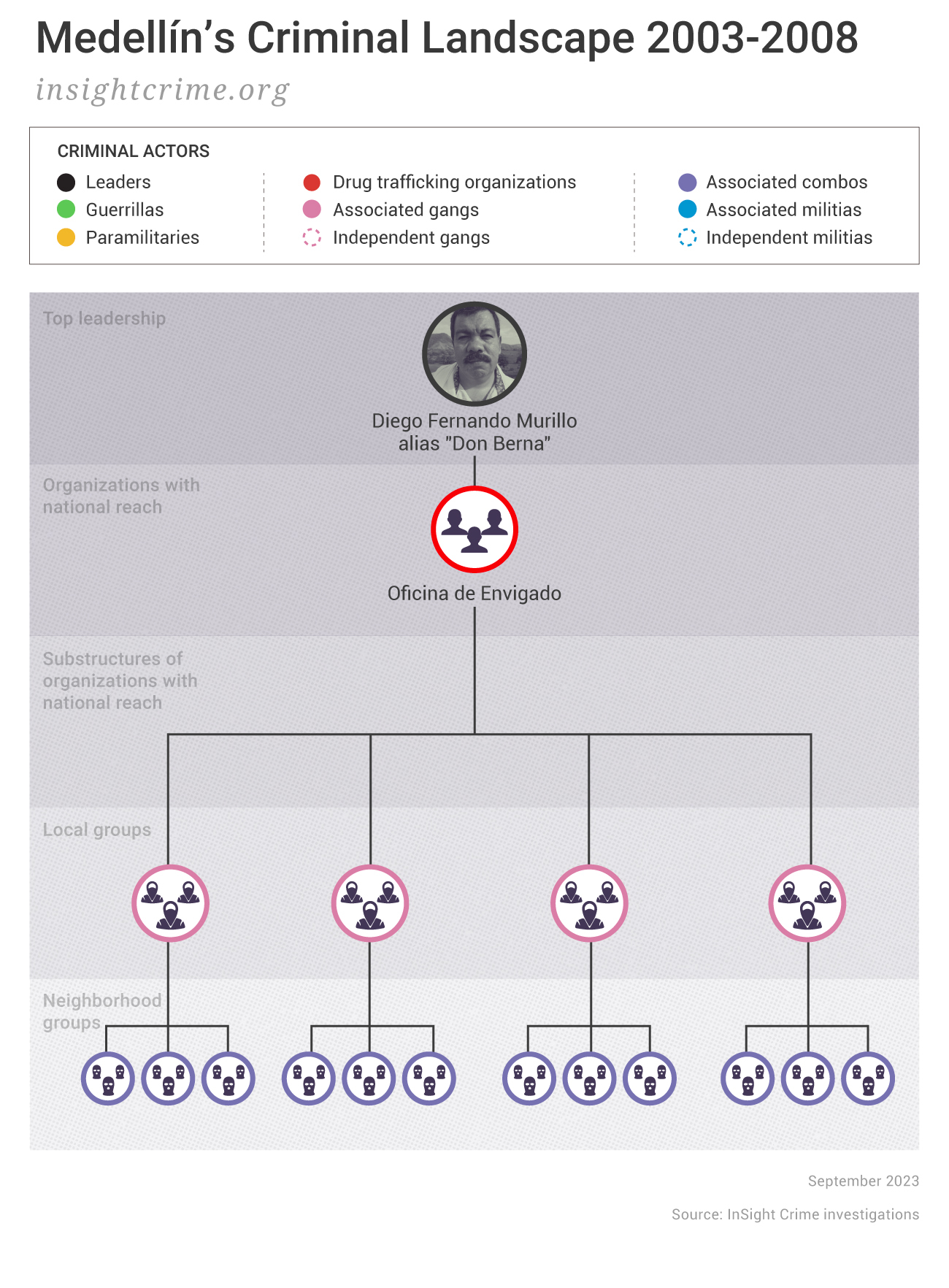

From Pawn to Power: The Criminal Rise of Don Berna

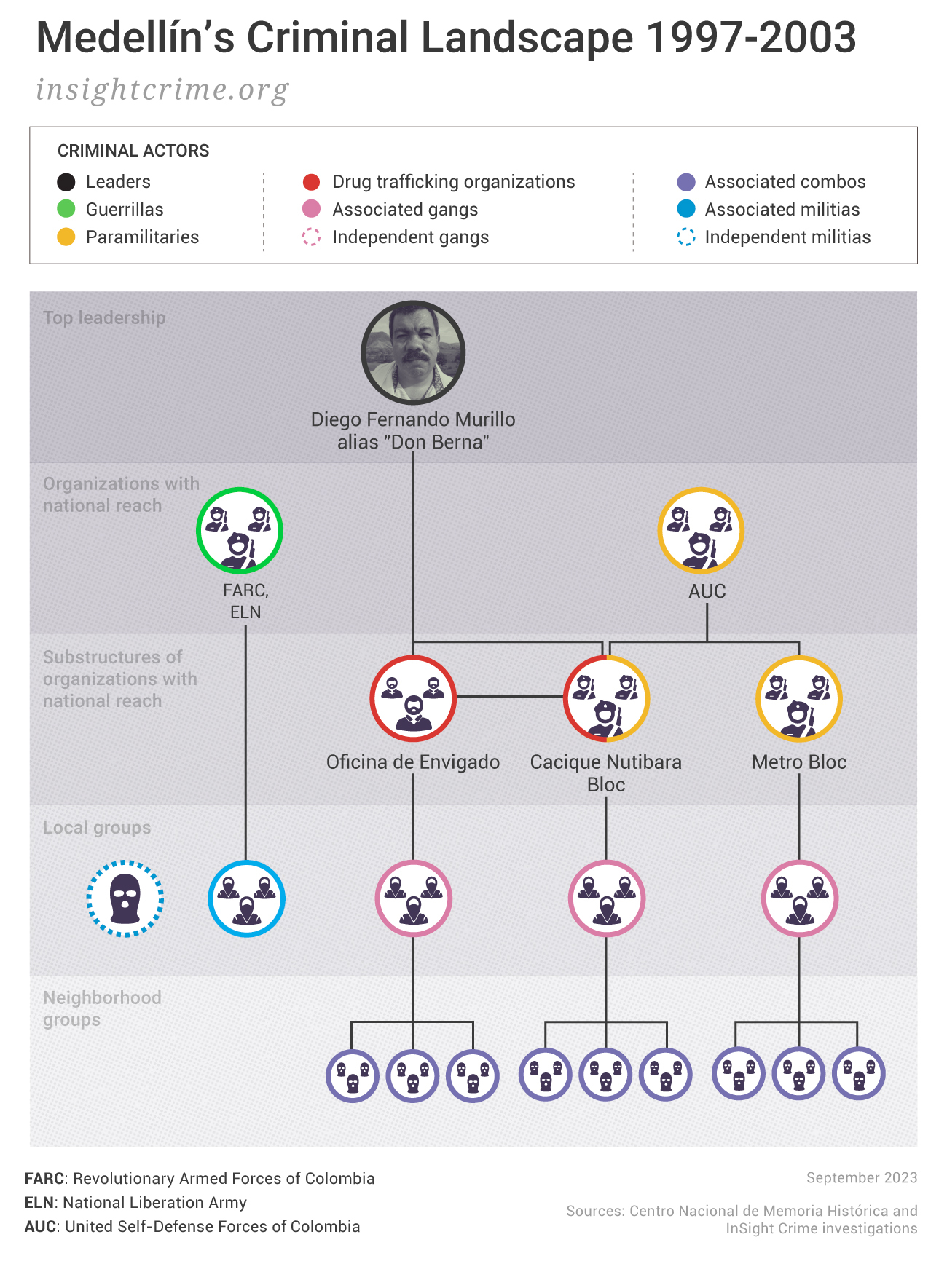

Little by little the paramilitaries began to push the militias out of Medellín’s neighborhoods. But even then, they were not the real power behind the city’s underworld.

In the chaotic aftermath of Pablo Escobar’s death in 1993, one man managed to bring Medellín’s criminal underworld together: Diego Fernando Murillo, alias “Don Berna.”

SEE ALSO: Colombia Elites and Organized Crime: ‘Don Berna’

Don Berna was not the most likely candidate to fill the void left by Escobar. Like Holguín, he came from a humble background and had lived through different stages of Colombia’s conflict.

Also like Holguín, he began his criminal career with the EPL in the 1980s, later joining the ranks of the Medellín Cartel. Don Berna was part of the so-called Oficina de Envigado, which was in charge of collecting debts and ensuring that all members of the Medellín Cartel paid their dues to Escobar.

Don Berna became a major player in Colombia’s criminal underworld in the 1990s. When Escobar murdered Don Berna’s bosses over a money dispute, Don Berna turned against the capo. Along with Escobar’s other enemies, he helped form the PEPES (an acronym for “People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar”), which worked closely with Colombian security forces to bring down the drug lord.

In the decade that followed, it was Don Berna who brought together most of Medellín’s criminal underworld.

He assumed leadership of the Oficina de Envigado, which continued to act as a debt collection agency, but which now worked for the various narcos that had filled the vacuum left by Escobar. Don Berna created alliances with different gangs in the Medellín metropolitan area to establish broad territorial control.

Those alliances spawned a criminal enterprise that operated as a network with clear hierarchies, but also with the autonomy necessary for successful illegal operations. Instead of operating as a dictator, as Escobar had done, Don Berna positioned himself as judge, jury, and executioner of the crime world in Medellín.

Don Berna also allied himself with the AUC and presented himself as a paramilitary commander. But when the Colombian government offered the paramilitaries an advantageous deal in the form of a demobilization process, a conflict arose. On one side was Don Berna, for whom the peace process would be a way to cleanse his criminal past, and on the other was the Bloque Metro, which disagreed with the inclusion of drug traffickers like Berna within the AUC.

To confront the Bloque Metro, Don Berna deployed his own paramilitary bloc, called the Cacique Nutibara Bloc (Bloque Cacique Nutibara – BCN), under which he united many of the city’s gangs as an armed force.

Violence increased again. In 2002, the city had a new peak in homicides with 3,829 people murdered, a rate of 179.8 per 100,000 inhabitants.

The following year, the BCN wiped out the Bloque Metro. Both the militias and the ideologically motivated paramilitaries had disappeared. Crime had prevailed over politics, and Don Berna was on top of everything.

Don Berna and the BCN embraced the government’s demobilization proposal and in December 2003, the BCN was the first paramilitary bloc to demobilize, with 868 combatants submitting to the process, surrendering 497 weapons.

An Unexpected Proposal

The demobilization coincided with Holguín’s last stint in prison, where his sentence had been reduced to 10 years because he had studied and worked while incarcerated. In September 2005, with two months left in his sentence, Holguín was transferred to a prison in Itagüí, a municipality neighboring Medellín.

Holguín recalled that shortly after his arrival, he was in his cell when prison guards came and handcuffed him.

“You’re going to the boss,” they told him, pushing him out of his cell.

“I thought they were going to kill me,” Holguín told InSight Crime when he explained the experience.

The boss, it turned out, was Don Berna. The former druglord had turned himself in earlier that year under pressure from other AUC leaders after the Colombian Attorney General’s Office accused him of murdering a social leader.

Holguín recalled the conversation with Berna with terror.

“The controversial Henry Holguín,” said the most powerful man in Medellín’s underworld at the time.

“I was scared. My balls were up in my throat,” Holguín said.

The last time Holguín had been in Medellín, he had been expelled from the city precisely for refusing to be part of the AUC.

“I’m waiting for my freedom,” Holguín told Don Berna. “I’m not going to stay in the city, out of respect for you. Tell me if you’ll give me the chance to get out of here. I guarantee that I’ll leave this jail and go to the farthest place I can go.”

But Don Berna had a plan for Holguín.

“No one in this city can ignore everything you’ve done for peace,” Berna told Holguín. “We want you to work for the peace process, and we want you to do all the social work you want to do, in the territories of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia.”

Holguín accepted, enthusiastic about the idea of continuing his work for peace, and honored by the recognition and respect from Don Berna.

He was appointed a member of the board of directors of Corporación Democracia, an organization that emerged in May 2004, after the BCN demobilization, to oversee the process of reincorporation of former paramilitaries into civilian life.

Holguín was in charge of the organization’s social programs. He was looking to continue the peacebuilding he had begun in the 1990s, but this time with demobilized members of the AUC.

“There was a phenomenal moment when we held a national summit of all the demobilized self-defense groups. All the demobilized AUC commanders expressed their approval of the social project we presented to them, which made us really happy and excited,” Holguín recalled.

A Shattered Dream

Holguín’s dream of building peace through paramilitary demobilization soon crumbled as he began to notice a breakdown in the process.

“Suddenly there was a kind of criminalization of the leaders of these groups, both nationally and locally,” Holguín said.

The demobilization had been a facade that allowed Don Berna to maintain total control over the Medellín underworld. And it was evident even at that time.

Officials in Medellín told Human Rights Watch in 2009 that up to 75% of the demobilized were not actually paramilitary combatants. In 2011, a former AUC commander stated that the BCN demobilization had been fictitious and that the leaders received benefits while continuing their criminal activities. Once again, demobilization and disarmament in Medellín failed to prevent the recycling of cycles of violence and criminal structures.

The number of homicides decreased in the years following the BCN’s demobilization, from 3,829 cases and a rate of 179.8 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 2002, to 782 cases and a rate of 35.3 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2005. But this was a demonstration of criminal force by Don Berna, rather than the result of public policy. No gang member in the city could commit a murder without Don Berna’s direct authorization. For the first, but not the last time, Medellín was experiencing a peace based on criminal control.

The Corporación Democracia turned out to be another vehicle for criminal control. Apart from having a legal structure and certain legal activities, many of its leaders continued their criminal careers.

For Holguín, the straw that broke the camel’s back was the murder of a good friend and then leader of a criminal gang called the Pachelly on November 16, 2006. Holguín blamed the killing on former AUC paramilitaries, although no one has been convicted of the crime, and officially the identity of the killers remains unknown.

“It diminished my hope and made me very sad. And that led me to think that whoever was leading the process at that time valued their military interests more than what should be done socially,” Holguín said.

Disappointed, he began to look for opportunities outside the country.

“I said goodbye to everyone here, and I told [Don Berna] that the death of my friend was very sad, and that because of that sadness, my heart wouldn’t let me continue my social efforts here,” he said.

In 2008, Holguín decided to move to Spain. That same year, Don Berna was extradited to the United States along with other former paramilitary commanders, accused of continuing their illicit activities after the supposed demobilization. The criminal landscape of Medellín was once again leaderless and on the verge of a major change.

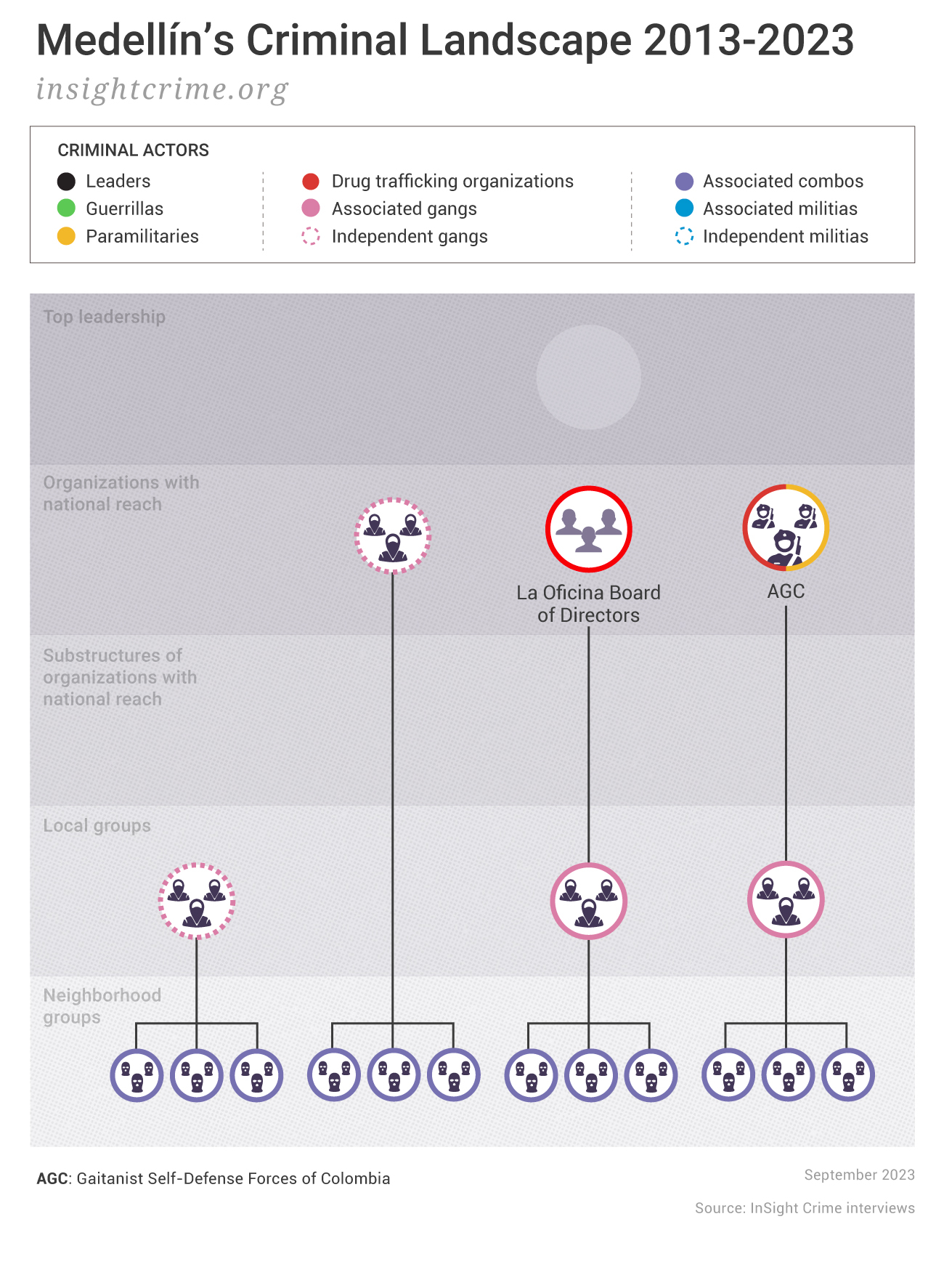

The Fragmentation of the Underworld

The extradition of Don Berna unleashed a war of succession that led to the total criminal fragmentation of Medellín, creating the underworld that Total Peace faces today.

Two of Don Berna’s lieutenants sought to fill the vacuum left by his absence, leading to a war that started in 2008 and reached its peak in 2009. That year, 2,186 homicides were registered in the city — a rate of 94 per 100,000 inhabitants — 1,141 more than the previous year.

Meanwhile, Holguín had moved from Spain to Peru, where he began working on peacemaking and citizen security issues for the local governments of the cities of Callao, adjacent to the capital Lima, and Piura, in the north of the country. From there, he followed the news about the confrontations in Medellín.

“I mourned the war because lots of friends always die in war,” Holguín recalled.

By 2012, the two rival lieutenants had been captured by the authorities. But the conflict continued. The city’s gangs were divided into two factions. One was made up of those that remained united under the banner of the Oficina de Envigado, now without a single leader. The other faction had joined the network of an invading criminal army: the paramilitary successor group called the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia – AGC).

SEE ALSO: Profile of the Gaitanistas – Gulf Clan

This new phase of the war ended in July 2013 with a pact between the groups. The pact was not negotiated by the authorities or peace mediators like Henry Holguín, but by shadowy drug traffickers and criminal elites concerned about the war’s effect on their illicit businesses.

This so-called “rifle pact” was an agreement without a political solution. It only aimed to bring down violence in order to maximize criminal opportunities.

Criminal groups had once again achieved what the peace processes initiated by the national and local governments had failed to do. Homicides dropped from 1,248 in 2012 (52.2 per 100,000 inhabitants) to 659 in 2014 (27 per 100,000 inhabitants), a reduction of almost 50% in just two years. By then, criminal groups had come to understand that violence brought unnecessary attention to themselves and their illicit economies and that maintaining low levels of violence could work in their favor.

At the same time, business was booming. Drug traffickers in Medellín benefited from the increase in cocaine flows and, free from the threat of turf battles, the gangs consolidated their control over criminal economies like extortion and microtrafficking.

They had also learned an important lesson. These pacts meant that criminality in Medellín would not have a single leader.

“All the criminal actors made the decision that they were not going to allow Medellín and the Aburrá Valley to have a top boss again,” Holguín said.

The underworld that the Total Peace negotiators are now facing a decade later was taking shape. It was becoming fragmented and leaderless, but entrenched, far-reaching, powerful, and with influence over the authorities themselves.

The result was an underworld made up of between 350 and 400 semi-independent local gangs called combos, which answer to between 15 and 20 major criminal gangs that control Medellín’s criminal markets through agreements among themselves. Some of these major structures form the Oficina’s leadership, providing services to transnational drug traffickers and other mafia elites. Others are allied with AGC drug traffickers, and some are independent.

A new cycle of organized crime had begun in Medellín. It continues to this day, and it is this cycle that Total Peace seeks to break.

The Pending Debts of Urban Peace

In 2015, peace was in the air in Colombia. The government was in talks with the guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC) to put an end to half a century of revolutionary war.

Medellín was also experiencing a type of peace, although very different from that negotiated with the guerrillas. Despite sporadic outbreaks of violence, the rifle pact had largely held.

When Holguín returned to his hometown that year, he met with former criminal colleagues he had worked with on the pacts in Bellavista prison in the 1990s. They told him about the changes in the underworld since the 2013 pact.

“They told me that things here had changed a lot,” Holguín said, his voice cracking with emotion. “[Conflicts] were being solved in a more peaceful way, through dialogue.”

This process involved criminals making agreements to keep violence rates low in order to avoid attracting the attention of the authorities rather than to end criminality. But Holguín saw echoes of the peace processes he had tried to lead in the past, as well as an opportunity for a new and more lasting peace in the future.

Holguín had returned to resolve a family problem but decided to stay after speaking with an old acquaintance, the priest Darío Monsalve, who had accompanied the Bellavista prison process when he was an auxiliary bishop in Medellín between 1993 and 2001.

“You are a generator of processes. Haven’t you thought of re-launching the Medellín process?” Holguín remembers the priest telling him.

Erasing the Line

With the support of church members, Holguín began to work with some of his old colleagues from the Bellavista non-aggression pacts, who, like Holguín, had been released from prison.

They held a meeting in a hotel in Medellín to organize the team and restart the processes from the 1990s.

The meeting caught the attention of the leaders of La Oficina, remnants of the infamous Oficina de Envigado.

“The leaders of La Oficina and the gangs — the real powers in the city — summoned me,” Holguín said.

They asked him what his interest was in returning to the city, and he answered that he wanted to revive the processes they had carried out in the past. For that, he said, the armed actors in the city needed to want peace and to be willing to participate. They were willing, they responded.

With that backing, Holguín started moving forward with his project.

“[We held] daily meetings to debate, to build,” Holguín said. Sinergia, a social movement for urban reconciliation, was born.

The newly formed organization sought the support of the local government to fulfill its mission. In January 2016, Holguín, representing Sinergia, presented the project to the newly elected mayor of Medellín, Federico Gutiérrez, accompanied by Monsalve, who acted as guarantor.

“We proposed to the mayor that we were going to create a social movement, which was going to be made up of social leaders from different sectors of the city and from the Church, and that we wanted the state to participate,” Holguín said about the meeting.

Gutiérrez confirmed this meeting to InSight Crime but clarified that it was requested by the former bishop in his personal capacity, not on behalf of the Sinergia movement.

At the time, the heads of organized crime in Medellín were seeking to reach agreements with the justice system. Between July and November, eight leaders and members of gangs and combos in the city handed themselves in, according to a report in the El Colombiano newspaper.

The gang leaders sought to obtain judicial benefits through a presidential decree issued in July 2016, which allowed the government to request benefits such as the suspension of security measures, or alternative sentences for those who served as peace promoters and helped strike humanitarian agreements.

In November of that year, a letter sent by members of La Oficina to then-President Juan Manuel Santos was also made public. In the letter, they expressed their desire to be included in an exploratory process for urban peace.

However, in July 2017, a major scandal engulfed La Oficina, Sinergia, and the local government, ending what little chance of peace there was at the time.

Then-Medellín Security Secretary Gustavo Villegas, who oversaw the surrender of several mid-level Oficina commanders, was captured for allegedly using his position to obtain favors from members of the criminal network.

According to the case made by the prosecutor, these favors included gang members turning themselves in to the police so Villegas could show off his achievements. In exchange, Villegas offered them judicial benefits, including the possibility of status as “peace promoters.”

Villegas’ alleged liaison with La Oficina was Julio César Perdomo, a demobilized AUC paramilitary and, at the time, a member of Sinergia.

Although much remains to be clarified about the case, it highlighted the fine line between mediation and collusion. And it led to a distrust of the Sinergia movement. Many of the group’s members withdrew and just a few people remained, among them Holguín.

The case also affected local institutions. On the one hand, it sowed mistrust in the population, and on the other, it left many public officials reluctant to get involved in peace issues, an issue that continues to this day.

“Politically it did us enormous damage. Sinergia was demonized,” Holguín lamented.

To this day, opinions about Sinergia are mixed. InSight Crime spoke to journalists, representatives of the institutions, and members of social organizations who view Sinergia with suspicion, some because of the presence of lawyers representing armed groups within the movement, and others because of the criminal records of many of its members, including Holguín.

The Total Peace Proposal

In 2018, a year after the Villegas scandal in Medellín, Colombia elected Iván Duque as president. The new president was not sympathetic to the peace processes begun by his predecessor.

Duque was a strong opponent of the peace agreement signed by the previous government with the FARC, and his approach badly affected the implementation of the accords. In early 2019, he put an end to peace talks with Colombia’s main remaining guerrilla group, the National Liberation Army, in Quito, Ecuador, following an attack on a Colombian police training school that killed 22 police cadets.

The Duque administration’s approach was echoed by the local government in Medellín and influenced how it handled the gang issue.

It took four years for the subject of peace to be discussed again in Medellín. But with new presidential elections approaching in 2022, then-candidate Gustavo Petro spoke of seeking a comprehensive peace in Colombia with different armed groups while on the campaign trail.

SEE ALSO: For Medellín’s Oficina Capos, the Shuffle is Part of the Game

“I felt the joy of hope,” said Holguín. After so many years, the prospect of peace was on the horizon once again.

Petro was elected president in June 2022. Shortly thereafter, Sinergia received a visit from Daniel Prada, formerly a lawyer for the newly elected president.

“He told us that Gustavo Petro stated … that he was going to deliver on his pledges for the Total Peace process and that they wanted a declaration of will [from the gang leaders]” said Holguín.

InSight Crime contacted Daniel Prada, who confirmed this meeting with Sinergia and explained that the objective was to learn about the gangs’ desire for peace, to know what their expectations were, and to present the government’s intentions for Total Peace to them.

With this green light, Sinergia visited prisons to get Medellín’s criminal leaders to sign up for the plans. The process took time. In the current structure of organized crime in the city, decisions require a consensus and agreement between many different actors.

But finally, the message of peace seemed to be near unanimous in Medellin’s underworld. El Colombiano reported on a meeting in August 2022 between the gang leaders in which they agreed to a truce between all the city’s gangs as a gesture of their commitment to Total Peace: no assassinations, no revenge killings, no territorial disputes.

The Uncertainties of Urban Peace

At the end of August 2022, the criminal gang the Pachelly expressed its willingness to join the Total Peace project in a letter sent to the government of Gustavo Petro. The gang designated Sinergia as its spokesperson, although Sinergia’s role has not been officially recognized within the process.

Soon after, other criminal structures in the city such as La Oficina, El Mesa, Los Chatas, La Terraza, and Los Triana expressed their willingness to be part of Total Peace in the city.

On June 2, 2023, after months of uncertainty about the progress of urban peace in Medellín and still without a legal framework for negotiations of this type, the national government set up a negotiating table in the La Paz prison in Itagüí.

A joint communiqué from the government and the armed groups put out that same day stated that the process would seek transformations to prevent new violence and achieve a successful reintegration of the members of the armed groups into society.

But so far, the plans for Total Peace in the city remain vague, while the challenges are great.

SEE ALSO: Colombia’s Risky Bet on Total Peace

As a result of the fragmentation of the underworld in Medellín, the government is not negotiating with one group but with the leaders of more than seven criminal organizations. However, these structures do not include all of organized crime in Medellín.

Jorge Mejía, coordinator of the government delegation in the La Paz prison dialogue space, told InSight Crime that the organizations they are in talks with represent 90% of Medellin’s organized crime. But several other gangs and combos are not included, while the AGC, which remains a powerful presence in the city, is in talks with the government in a parallel but separate process.

Furthermore, the leaders that are at the table may have different interests than the lower-ranking members of their gangs outside of prison, many of whom do not have open judicial proceedings against them and so do not face the same personal pressures.

Medellín has already seen murders committed by gang members outside of prison while their leaders negotiate with the government inside. These killings appear to be the result of disputes within one of the gangs participating.

Similarly, smaller armed structures such as the combos may have different views from those of the gangs that are negotiating with the government.

“If you don’t include the structures considered low impact, they are going to fill the gaps of the big ones with dizzying speed,” Carlos Zapata, president of the Popular Training Institute (Instituto Popular de Capacitación – IPC), an NGO that works on peace, democracy, and human rights issues, told InSight Crime.

In addition, Total Peace will have to confront the ghosts of past experiences, as is clear from Holguín’s history. The peace process with the guerrillas in the 1980s; the fall of Pablo Escobar; the demobilization of the militias and the pacts between gangs in the 1990s; the paramilitary demobilization in the 2000s and the non-aggression pacts of La Oficina afterwards have all failed to end the conflict in the city.

Instead, they have led to a recycling of violence marked by armed groups’ continued control of large areas of the city and criminal economies, and their continued impact on Medellín security dynamics. Rather than dismantling the city’s underworld, these processes have instead led to its evolution, in the process creating many of the challenges facing Total Peace today.

“Organized crime is totally transformed and has learned from all the peace processes, especially from the failures of the state” the academic who accompanied the pacts in the 1990s told InSight Crime.

Overcoming Obstacles

The government’s main challenge is now to use the space opened up with the gangs to find answers as to how to put an end to the cycles of violence in the city rather than just negotiating the terms of surrender for individual leaders and members of criminal groups. It must also confront the state’s own shortcomings and its historical absence in the most marginalized areas of the city.

The gangs, in turn, face the challenge of showing they have a genuine desire for peace, and to contribute to the dismantling of criminal networks in order to prevent them from being revived in different forms.

Many following the process remain skeptical.

“What are the gangs going to give up? Are they going to tell the truth? Are they going to hand over [trafficking] routes? Are they going to hand over their allies in the legal and illegal worlds? Are they going to hand over national or international allies? Is there going to be a total abandonment of criminality?” said Juan Diego Restrepo E., director of Verdad Abierta, a media outlet dedicated to investigating the Colombian conflict.

In response to such doubts, Jorge Mejía told InSight Crime that this is a discussion that will take place at the negotiating table once the protocols and work agenda have been defined, but mentioned that the members of the groups have informally expressed their willingness to take on these challenging topics.

Doubts about the motivations of the gang leaders also weigh on some of their spokespeople and representatives, including organizations like Sinergia and individuals like Holguín.

“Sinergia is one of many socio-legal organizations that try to represent the gangs in peace projects. They are organizations that are run by criminal lawyers and ex-gang members and every time there is a peace process, they try to insert themselves with proposals that end up benefiting the leaders who are in prison,” Medellin-based investigative journalist Nelson Matta told InSight Crime.

Holguín, though, is convinced that the armed actors at the table are committed to the process. And although there will be no easy solutions to such deep-rooted problems, he claims that they already have proposals to be discussed at the dialogue table.

“This dialogue space has been generated precisely to deal with all those kinds of issues, which are inherent to urban conflict,” he said.

And where others have seen how the challenges from past experiences persist today, he sees opportunities to learn from the past so that this process can be different.

“There are two things that are being brought together [at the table]: lived experiences, with all the lessons that these have left us with, and the active participation of the communities, organized around these scenarios of inclusion and participation so that we are working together,” said Holguín.

His hope for the process stems from his own life experiences. And today, Holguin, a gangster turned peace promoter, is optimistic that those sitting at the table with the government can succeed where the generations before them failed.

And he hopes that his life will be a message to others who, like him, have been combatants in urban warfare in Medellín:

“At least I am a good life reference for today’s gang leaders, who know that I could also be a leader but that I decided to live a quiet life, to walk in peace. Because I am in a peace process that I believe in and that I am proud of,” he said.