The blood streamed down Eduardo Labrador’s face and splattered across his shirt. “Film me! Film me!” he shouted at the journalist who had come to check on him. As he addressed the camera, he was defiant, angry even. Today, he said, they had come out to defend democracy in Venezuela. And this was the result.

One year later, he grasped for an analogy for what it felt like to be beaten. “I don’t know if you’ve ever experienced an explosion, you feel it there, so close to your ears — Boom! For hours I heard that boom in my ears,” he told InSight Crime.

The image of Labrador, blood-streaked and indignant, shattered the façade of an orderly and peaceful election that the Venezuelan government had been desperate to present to the world.

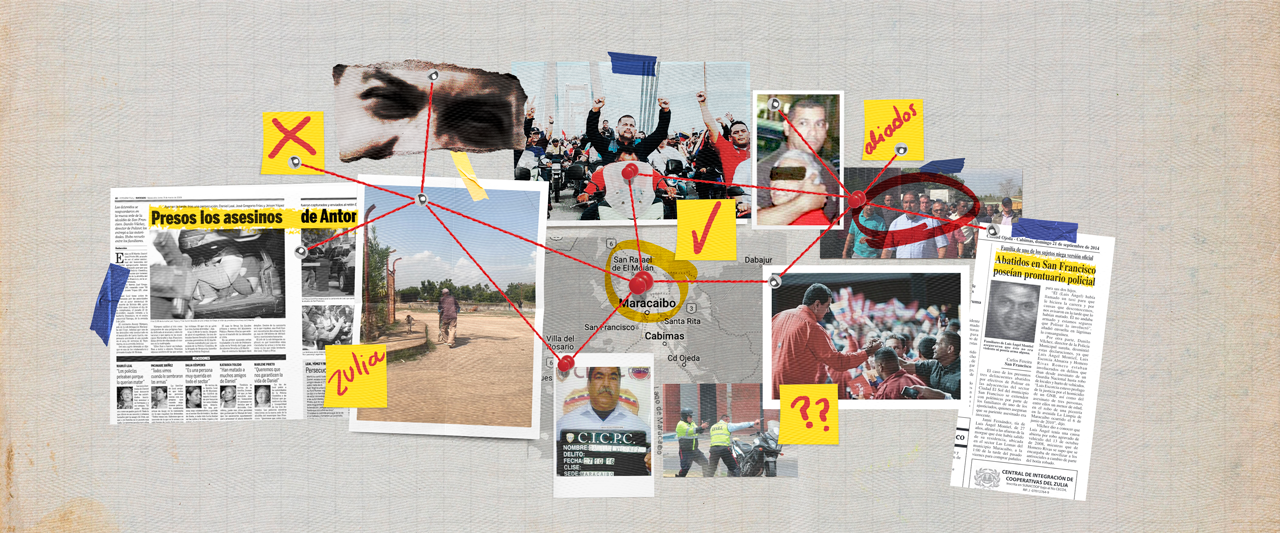

Labrador had been attacked by armed men as he tried to carry out his duties as the campaign director for the political opposition during local and regional elections in November 2021. The assault, he says, was part of a premeditated campaign of voter intimidation in the municipality of San Francisco in the northwestern state of Zulia. And behind that campaign, he alleged, was Zulia’s then-governor Omar Prieto.

Labrador had witnessed Prieto’s rise firsthand as a political ally within the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela – PSUV) and member of his cabinet. He was often seen as Prieto’s right-hand man.

But over time, Labrador watched the socialist project he had once believed in descend into what another former high-level PSUV insider described to InSight Crime as “a project of crime in power.”

That project saw Prieto and his cronies carry out extortion, embezzlement, theft, and smuggling rackets from within the state, while deploying a criminalized police force as a private militia to protect their interests.

It was a project very much of that moment in Venezuela’s history.

When Prieto became governor in 2017, Venezuela was on the brink of economic collapse, and President Nicolás Maduro was under political siege. Desperate to maintain the loyalty of a fractured PSUV, underpaid security forces, and military and political elites unhappy with their dwindling corruption profits, Maduro granted territories to the different poles of power within the Chavista political movement. And then he gave them permission to squeeze whatever criminal profits they could from those territories.

Prieto was granted power in Zulia as a scion of the most important political faction within Chavismo outside of Maduro’s own network. And for the duration of his term, he pushed that permissiveness to its limits.

But by the time he was standing for reelection in 2021, that moment was beginning to pass. Venezuela had a measure of stability. Maduro’s presidency had survived, and his objectives were shifting. He wanted to reenter the international community both politically and economically. He wanted to consolidate his personal power and neuter his rivals within the PSUV. And he wanted to bring order to the mafia state that had grown up during the crisis.

Which is why Maduro invited international observers to monitor the 2021 elections, in the hopes that they would tell the world the elections were free and fair. And why even when it became clear the PSUV was going to lose Zulia, he made no intervention to help Prieto, who had overstepped the conventional limits on criminality and corruption.

Venezuela’s 2021 elections were problematic but largely peaceful. The violence in Zulia, which left one dead and three — including Labrador — injured, was a shocking exception. But it was entirely predictable. Prieto, the gangster governor, was never likely to go quietly.

PART 1

The Two Omars

In 2009, after three months of hunting, the Venezuelan police had their man. They positioned sharpshooters at strategic points around the town of San Francisco and dispatched an armored unit to chase down the black Toyota 4Runner the target was traveling in. They found the car behind city hall, abandoned, with its doors flung open. Daniel Leal Prieto, leader of the Los Pulgas (The Fleas) gang, and his two accomplices had barricaded themselves inside the municipal seat of power.

Leal, better known as “Danielito,” was wanted for the murder of Antonio Meleán, head of the Meleán crime clan and godfather of the Zulia underworld. He had headed to city hall to seek protection from his childhood friend and one of the most powerful men he knew — Omar Prieto, mayor of San Francisco.

A crowd of Danielito’s family members and friends, who’d followed the police chase, gathered outside city hall shouting and crying, and at least two women fainted, according to accounts in local media.

“Daniel came here to speak to Omar Prieto, who is his friend. He was going to ask for [Prieto’s] help, to guarantee his safety,” Danielito’s sister told Venezuelan news media.

Prieto dispatched his municipal chief of police to manage the standoff with the national police officers and keep Danielito safe. After hours of negotiations, Danielito was taken into custody unharmed.

For Prieto, Danielito’s appearance represented two worlds colliding, his criminal past gatecrashing his political present just months after assuming office. Within a year, Danielito would be killed in prison. Prieto, though, would be a rising star in Venezuela’s political establishment.

Starting Young

From the beginning there were two Omars.

The state’s future governor was born in 1969 into the middle-class neighborhood of Sierra Maestra, which today is part of Zulia’s San Francisco municipality.

A neighbor who knew Prieto growing up described Sierra Maestra as a calm place where children play in the street. The Prietos, the neighbor said, were an old Sierra Maestra family: average people, who were involved in the community and had enough to live comfortably but were not rich.

When asked about Prieto, however, she paused to think. “He is not a person, he is a demon,” she said.

“He is not a person, he is a demon.”

Like many sources cited in this story, the neighbor asked for anonymity out of fear for her personal safety. Many others refused to speak altogether or backed out at the last minute.

Prieto’s ties to Zulia’s underworld stretch back to his youth. While he claims he was dedicated to the practice of taekwondo and the study of economics at the University of Zulia, it is an open secret that he was also part of the same gang as Danielito, Los Pulgas.

The San Francisco street gang was dedicated to car theft and extortion. Even at university, Prieto was known by the nickname “Toyotica” because of his preference for stealing Toyota-brand cars, one long-time associate told InSight Crime.

“He started off very young, making friends with strangers,” an established San Francisco political leader told InSight Crime. In Venezuelan slang, making friends with strangers means making friends with criminals.

After graduating, Prieto worked as a pharmaceutical sales representative and started his own taekwondo school. But by the 2000s, as President Hugo Chávez was beginning his long tenure as Venezuela’s leader, Prieto had changed tack and begun to search for an opening in politics.

SEE ALSO: The Shattered Mafia Behind Criminal Chaos in Zulia, Venezuela

Early on, Prieto showed no particular interest in socialist or leftist ideals, and his first attempt to get into politics in 2001 was with the opposition party, Primero Justicia (PJ).

“His pitch to Primero Justicia was that he had the money to become mayor of San Francisco and all he needed was a party card,” one of the party’s leaders, Juan Pablo Guanipa, told InSight Crime. “We told him we were not a franchise that he could buy into.”

After that rejection, Prieto ran unsuccessfully for San Francisco mayor on the communist party ticket in 2004. Undeterred, he was elected in 2005 as an alternate representative to Venezuela’s National Assembly for the party led by Chávez, the Fifth Republic Movement (Movimiento V República – MVR).

Prieto served in that role until 2008, when he launched a new bid to become mayor of San Francisco, this time as a candidate for the newly formed PSUV, which was founded by Chávez to unite Venezuela’s disparate leftist parties under one banner.

Throughout Zulia, the elections that year were marred by PSUV infighting, voter intimidation, irregularities, and military interference. But Prieto, buoyed by a personal endorsement from Chávez, emerged from the chaos victorious.

Those who knew Prieto, however, say that the PSUV was little more than a convenient vehicle for his ambition.

“He wasn’t a Chavista. He took advantage of an opportunity,” a University of Zulia professor who knew Prieto told InSight Crime. “Once he was in power, he got worse and used methods that weren’t accepted, that were ‘out of bounds,’ even for the PSUV.”

Thugs With Badges

Though the Danielito incident marred his first months in office, Prieto was a popular first-term mayor.

Bankrolled by the national government in Caracas, he launched an ambitious program of public works that included access to potable water, a stable gas connection, and a new hospital specializing in the treatment of childhood cancer. Prieto was also politically savvy, dedicating his projects and public works to Chávez.

“He had a lot of influence in the community,” a businessman and political expert close to Prieto told InSight Crime. “The criminal accusations didn’t matter to many people as long as they got help.”

But it was not only Prieto’s public works that made him popular. He also garnered support for his hardline approach to rising insecurity, even though it led to a rise in extrajudicial killings and police abuse.

Before Prieto’s arrival, the municipal San Francisco police department, known as Polisur, had been rated one of the best in Venezuela by oversight agencies, according to Provea, a Venezuelan human rights NGO that studies police abuse. After just one year with Prieto in charge, Provea ranked it as the fourth most abusive police department in the country owing to repeated complaints of excessive force, as well as cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment.

Current and former security officials and PSUV insiders described how the new mayor regularly broke protocol to fill Polisur’s ranks with contacts from his past, many of them without qualifications and some of them with criminal records. Polisur became what numerous sources described as a “police mafia.”

In addition to its violent approach to cleaning up the streets, Prieto’s police mafia also formed the enforcement arm of a nascent criminal enterprise focused on extorting the private sector.

“The San Francisco police turned into thugs with badges,” a former high-level government official told InSight Crime.

According to former Prieto insiders, as well as former security officials and civil society leaders in San Francisco, officials would demand that businesses show them paperwork they were not required to have or that did not even exist, then demand a bribe when they could not produce it.

“Restaurants, manufacturing companies, companies related to agricultural activities, all had to pay vacunas [“vaccinations” or extortion fees] in dollars with the threat that if they did not comply, they would be expropriated,” a former PSUV leader who knew Prieto since his university days told InSight Crime.

In the first years of Prieto’s tenure, the mayor’s office ordered a series of controversial expropriations in San Francisco, including of industrial and residential land, asphalt distributors, gardens, cultural centers, and markets.

Meanwhile Prieto himself began cultivating the aura of head gangster. Everywhere he went, he was surrounded by an entourage of cars and armed bodyguards, a sight that would become part of his signature look.

“Omar liked to demonstrate and flaunt his power,” the former PSUV leader and Prieto’s ex-confidant said.

Mafia in the Mayor’s Office

While Prieto continued to receive backing from the Chavista government in Caracas, he began to alienate some of those who had dedicated their careers to the socialist project in Zulia, sowing the seeds for a conflict that would deepen over the course of Prieto’s political ascent.

By the time Prieto ran for mayor, Eduardo Labrador had been an active member of the militant socialist movement for over two decades, having joined when he was 14 years old. When Chávez became president in 1998, Labrador joined Zulia’s newly formed Optimistic People Party (La Gente Optimista – LAGO), which aligned itself with the Chávez government and became the core of the state’s leftist establishment.

Prieto had needed LAGO’s support to become mayor. In exchange, he named Labrador his second-in-command, making him San Francisco’s cabinet secretary.

“I was always by his side after that, so many people saw me as his right-hand man,” Labrador told InSight Crime. “But we were like water and oil. Together but not mixing.”

It did not take long for the tensions to spill over.

Labrador remembers an incident less than two months into Prieto’s first term as mayor, when Prieto abruptly rushed both of them out of a government meeting, in a panic after hearing that state police had arrested Ebyck Andrade, his former bodyguard and a newly minted Polisur officer.

Labrador said Prieto took him to Zulia’s state police headquarters, speeding in his car and crashing into the facility’s security barrier, injuring the on-duty guard and setting off alarms. Amid the chaos, Prieto’s ever-present bodyguards pulled out their weapons and there was an armed standoff with the police.

“One wrong move and it would have been a massacre,” Labrador said.

In the end, state police released Andrade who, together with another Polisur officer, had been accused of drunk and disorderly behavior after allegedly brandishing his service weapon during an argument at a baseball game.

The standoff soured Prieto’s relationship with Zulia’s state police chief Jesús Cubillán, making headlines as the two men hurled accusations of corruption at each other, even as Prieto’s team tried to do damage control.

Andrade, though, was soon promoted to chief of Polisur’s Internal Affairs, where he became the subject of a new and even more serious scandal.

In June 2009, Andrade allegedly led seven other Polisur officers in the kidnap, torture, and rape of a San Francisco youth, who had to be hospitalized for internal injuries. The officers accused the youth of drug trafficking and murder but failed to produce any credible evidence. An anonymous police source later told Venezuelan news media that the real motive for the attack was the youth’s friendship with Andrade’s girlfriend.

The scandal dominated regional headlines for weeks.

Andrade and the other Polisur officers were detained, and Zulia’s public prosecutor opened a high-profile investigation into alleged police abuse. But the case quickly fell apart. Andrade and his co-defendants were initially allowed to await trial in the Polisur police station but were quickly released. Finally, the victim, whose family had repeatedly complained about receiving death threats, withdrew his testimony.

Andrade resumed his work for Polisur and was appointed deputy director of the municipal police force less than a year later, according to an article published by Provea.

Labrador, after publicly promising that Prieto’s administration would deliver justice, was shocked.

“This was our first really big rift after Prieto became mayor,” he remembered with some bitterness. “It was a rift over human rights violations, terrible violations that no human should permit.”

A Man of His Time

Prieto’s brazen disregard for established boundaries may have scandalized the left in Zulia, but on a national level it was simply ahead of its time. In Caracas, where the Chavista grip on power was wavering, some within the national government were starting to see the utility of a brash and ambitious man like Prieto.

In 2013, the same year that Prieto was re-elected mayor of San Francisco, Chávez died. He passed the presidency to his significantly less popular vice president, Nicolás Maduro, who inherited a mismanaged economy, pervasive corruption, mounting insecurity, and plummeting oil prices.

By 2014, Venezuela was in crisis, and thousands of protestors spilled onto the streets, railing against insecurity, chronic inflation, and the scarcity of basic goods. They called for Maduro’s resignation.

Then in late 2015, legislative elections gave the political opposition a two-thirds supermajority in the National Assembly. Maduro responded by stacking the supreme court and creating a parallel legislative body, the Constituent National Assembly. And Venezuelans responded with more mass demonstrations in 2016 and 2017.

Maduro met the threat to his position with brutal force, normalizing and even rewarding violent repression.

Prieto’s “police mafia,” the Polisur, embraced the new permissiveness.

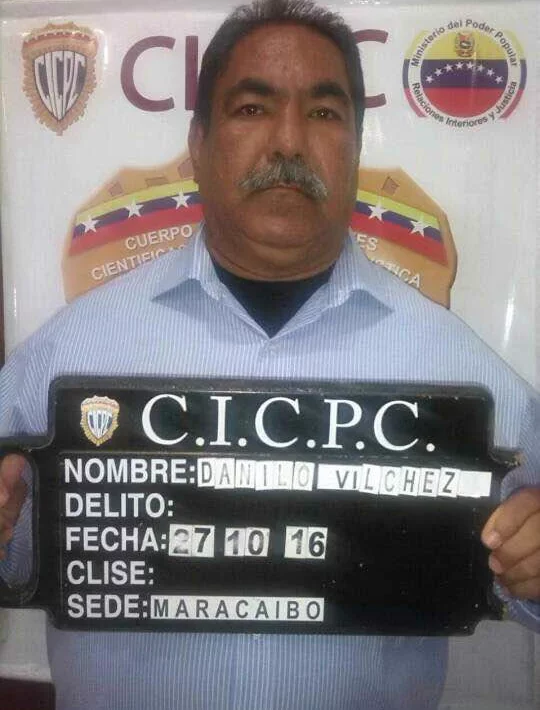

In October 2016, Prieto’s Polisur director, Danilo Vílchez, personally led his officers in a violent attack against protestors, landing several of them in the hospital. He was acting on Prieto’s orders, protestors and opposition leaders told Venezuelan news media.

The scandal was widely reported, and finally General Néstor Reverol, an important military figure who had been recently appointed Minister of the Interior, Justice, and Peace, intervened.

Reverol ordered Vílchez’s arrest and suspension from his post as Polisur’s director. But Vílchez would not be gone for long. In less than a year, Prieto would name him San Francisco’s security secretary, although he would join Prieto in the governor’s office before assuming the role.

A Deal With Two Devils

Though Maduro never publicly commented on Polisur’s abuses, Prieto’s ability to crush dissent in one of Zulia’s biggest municipalities made a tangible contribution to his fight to maintain power. Permissiveness, including towards Vílchez, appeared to be Prieto’s reward.

But Maduro was not the only one who saw Prieto as useful.

Since Chávez’s death, Venezuela’s ruling class had broken into several rival political factions. The most powerful of these were the faction led by Maduro himself and another bloc led by Diosdado Cabello, a former military general who many within the movement saw as Chávez’s rightful successor.

Prieto’s disregard for the rules caught the eye of Cabello’s right-hand man, Pedro Carreño. Given the opportunity to make more powerful friends in Caracas, Prieto seized his chance.

He secured Carreño’s patronage by fulfilling his appetite for vice, Labrador, another former member of Prieto’s inner circle, and a businessman with connections to the Prieto administration told InSight Crime.

“He would get him all the whiskey he wanted and set him up in a house in [Zulia’s state capital] Maracaibo, hosting orgies, bringing him girls, showering him with dollars in cash,” the former PSUV leader and Prieto’s ex-confidant said. When contacted by InSight Crime, Carreño strongly denied all the allegations made in this article.

After courting Carreño, Prieto got access to Diosdado Cabello.

The decision was yet another point of friction with Labrador.

“I told him, I’m not switching to Cabello’s [faction]. I’m with Maduro, because that’s what Chávez asked of us,” he recalled.

But with or without Labrador, Prieto had made up his mind to throw in his lot with Cabello. In doing so, he would get a shot at expanding his domain from San Francisco to all of Zulia.

In 2017, opposition leader Guanipa beat incumbent governor Francisco Arias Cárdenas in Zulia’s state elections. But Guanipa refused to take an oath to the highly controversial National Constituent Assembly, which critics said was created to usurp power from the National Assembly, the only branch of government under opposition control. Caracas disqualified Guanipa’s victory and called a special re-election.

To the surprise of many insiders, the PSUV leadership chose Prieto over Cárdenas to contest the election. Cabello himself announced Prieto’s candidacy and Carreño, by this time the PSUV’s president in Zulia and Trujillo, worked hard to promote him on the campaign trail.

On December 16, 2017, Prieto was sworn in as Zulia’s new governor by Carreño, whom he thanked for “teaching me the strategies to win.”

PART 2

Testing the Limits

In the dead of night on February 1, 2018, 500 troops descended on Las Pulgas, one of the biggest informal markets in all of Latin America, which lies in the heart of Zulia’s capital Maracaibo. One hundred more would join them as dawn broke.

Merchants say that soldiers and police officers looted the market, destroying their stalls and stealing their wares.

“You can’t imagine. It looked like Ukraine — like a war zone,” a community leader for the Pulgas merchants told InSight Crime.

Prieto’s administration justified the raids as a necessary measure to end informality and criminal activity in the market, but former Prieto insiders and business leaders told InSight Crime they believed the real objective was to bring that activity under Prieto’s control.

Later raids established a permanent security force presence in Las Pulgas, but the black market continued to flourish under their watch, according to Venezuelan news media.

Las Pulgas merchants “began being charged ‘tariffs’ or ‘taxes’ in dollars. These weren’t going into the state’s coffers,” Zenaida Fernández, a former PSUV legislator and Indigenous representative, told InSight Crime.

Merchants responded with protests, accusing Prieto of breaking a decree passed by Chávez which protected even the informal vendors of Las Pulgas from government interference.

Prieto met them surrounded by soldiers and riot police that were armed to the teeth. “Listen carefully, because I’m only going to say this once. The intervention in Las Pulgas is absolute,” he told them.

Prieto had been governor of Zulia for just two months, but it was already clear how he intended to rule.

Assuming Power, Imposing Fear

Prieto’s transformation into the gangster governor was almost immediate.

He moved into the governor’s residence with powerful new political godfathers in Caracas in the form of Pedro Carreño and Diosdado Cabello. Being part of such a powerful political faction earned Prieto protection and influence. But in Venezuela, such patronage rarely comes for free.

Once there, he followed the prevailing governance model of the time, in which the national government gave power-players free rein to squeeze profits from their territories in any way possible.

Prieto’s first moves were to scale up his San Francisco operations.

As soon as he became governor, Prieto promoted the men who had been responsible for turning the San Francisco police into a criminal militia. He made former municipal intelligence police chief Luis Curiel head of the Intelligence Police Force (Dirección de Inteligencia y Estrategias Preventivas – DIEP) for all of Zulia. He also promoted former municipal police director Danilo Vílchez, naming him to security secretary for the whole state.

“I’m counting on you to replicate our success in San Francisco throughout all of Zulia,” he wrote in a caption to a photo of Vílchez accepting the promotion.

And that is exactly what they did.

Almost immediately, police abuse grew in scope. As well as protesters and common criminals unaligned with Prieto, journalists, political rivals, and others who threatened to expose his police mafia became targets of his administration.

In May 2018, Vílchez attempted to strangle a protesting nurse with his bare hands, capturing the essential perversion of security forces’ role under Prieto.

Under Curiel and Vílchez, the security forces also scaled up their extortion operations.

“There is no business that doesn’t pay a vacuna here,” a high-ranking opposition figure in Zulia told InSight Crime during an interview held when Prieto was still in power.

This ramped-up criminal activity and state violence began testing the limits of what was allowed in Maduro’s crisis-ridden regime. And some in Caracas were not on board.

Growing tensions in Caracas over Prieto’s behavior became apparent in August 2018, when Interior Minister Néstor Reverol was sent back to Zulia. He was not happy to see Vílchez, whose arrest he had ordered two years earlier, in a position of even greater power.

Reverol suspended both Vílchez and Curiel, replacing them, respectively, with Rubén Ramírez Cáceres and Benito Cobis — two men outside of Prieto’s direct sphere of influence. This time, neither was reinstated.

Cobis immediately began investigating allegations that the DIEP — the agency previously run by Curiel and now under his control — had become home to a sophisticated extortion network.

On October 5, 2018, a little over a month after taking on the posting, Cobis and his bodyguard were gunned down while returning home from a patrol. Local media reported that the two security officers died in a “storm of bullets.” Cobis alone was shot twenty times.

The DIEP commissioner’s violent death dominated the news cycle, and Reverol did not take kindly to the murder of his man in Zulia. He sent the head of Venezuela’s Criminal Investigations Unit (Cuerpo de Investigaciones Científicas, Penales y Criminalísticas – CICPC), Douglas Rico, to personally lead the investigation. Rico quickly concluded that the murder was an inside job.

Less than a week later, a team under Rico’s command raided DIEP headquarters, temporarily stripping hundreds of officers of their weapons. In the end, six DIEP officers were arrested and charged. Curiel, who had been caught on camera en route to the murder scene, was one of them.

The investigation concluded that Cobis had been killed for probing into his colleagues’ criminal activity. It also found that more than a third of the DIEP’s 210 agents had been given police credentials without actually belonging to any branch of the security forces.

By the end of November, Prieto was forced to dismantle the DIEP. Vílchez was permanently removed from Zulia’s government. Curiel and his five accomplices were arrested for Cobis’s murder, although they were released from prison five years later.

Reverol made sure that the investigative agency created to replace the DIEP, known as the SIP (Servicio de Investigaciones Policiales), was outside of Prieto’s control. It was headed by a colonel loyal to Reverol, and its corps excluded anyone who had served in the DIEP.

And yet the blow to Prieto’s control, while not insignificant, was temporary.

Even with the DIEP gone, Prieto still had control of the Polisur, the municipal police force of San Francisco, where Prieto’s childhood friend Dirwings Arrieta was now mayor. As for Vílchez’s replacement, Ramírez Cáceres, he would only last a year as Zulia’s security secretary before Prieto forced him into retirement and replaced him with another ally.

Even without Vílchez or Curiel at the helm, police abuse persisted in Zulia. According to the Commission for Human Rights in the State of Zulia (Comisión para los Derechos Humanos del estado Zulia – Codhez), 239 people died in supposed clashes with the police between January and June 2019. These often lacked any sign of struggle and only one police officer died in the reported confrontations.

Surviving Reverol’s political attack emboldened Prieto to push the limits of Maduro’s permissiveness even further than before.

“I know the world of politics here. It is a perverse world. But the most unfortunate, the most perverse thing, is what they did through the governor’s office,” Labrador said of this period in Prieto’s term.

‘Damn, He Was Born Corrupt’

The power struggle with Reverol did little to slow what Prieto had set in motion. Under his administration, a vast criminal network involved in embezzlement, expropriation, and extortion continued to evolve. Its members were embedded in the state and relied on government authority to redirect profits from private industry, state infrastructure, and even criminal economies.

“The aim was to get into all the businesses, all the ’little puddles,’” Labrador said, adding after a thoughtful pause, “That boy. Damn, he was born corrupt.”

Having been removed from his position as security secretary, Vílchez became part of this network. Several sources, among them current public officials and political leaders, claim Vílchez was involved in Prieto’s efforts to secure control over Zulia’s most precious resource — gasoline.

After coming to power, Prieto seized many of the subsidized gas stations that supplied most of Zulia’s population with fuel, bringing them under the control of his allies and associates. These gas stations also acted as contraband hubs, supplying black market fuel both to the local market and to be smuggled into Colombia.

Following Prieto’s exit from office, many of those gas stations were returned to their owners. Since then, accusations have arisen that Prieto never paid the state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA), for gasoline delivered to the stations during that time.

“I’ve had gas station owners come to me and say, ‘PdVSA says I owe them, but it’s not me who owes them!’ [Prieto’s people] put the burden on the gas station owners!” Labrador told InSight Crime.

Control of gasoline supplies also became a way to form and cement alliances with military commanders in Zulia, whose involvement in gas smuggling is well documented.

Although he had relationships with everyone in the military, Prieto was especially close to Gen. Manuel Enrique Castillo Rengifo, according to a former security official with connections among active intelligence forces.

Rengifo, named in 2020 to head Zulia’s most important military command, the Operational Zone for Integral Defense (Zona Operativa de Defensa Integral – ZODI), would go on to be a loyal ally to Prieto.

Managing Prieto’s relationship with the military was the responsibility of another key member of his inner circle, his cabinet secretary and right-hand man, Lisandro Cabello, who shares a name but no known relation to Diosdado Cabello. Cabello acted as a stand-in when Prieto was unavailable and managed many of his shadier operations, including the 2018 military raids on Las Pulgas. Lisandro’s brother, William Cabello, also played a role in Prieto’s network, according to PSUV insiders.

Labrador came up against William Cabello when he opposed a resolution giving the governor’s office control over La Chinita International Airport in Maracaibo airport, because, he said, he knew the cargo and concessions “taxes” they collected would never reach the state’s treasury.

Control of the airport, along with control of tolls collected from vehicles passing over the Rafael Urdaneta bridge, which connects Maracaibo to the rest of the country, were sources of easy money for Prieto’s network, several PSUV insiders alleged.

“A Lawyer for Evil”

Of all Prieto’s fixers and enforcers, one seems to have made the biggest impression on PSUV insiders: his state attorney general, Rebeca del Gallego.

“State Attorney General Rebeca del Gallego is an intelligent woman,” the former PSUV leader and Prieto’s ex-confidant told InSight Crime. “But she’s a lawyer for evil.”

During Prieto’s four years in office, del Gallego became synonymous with Prieto’s most notorious and visible operations: illegal expropriations.

Expropriation is a legal and recognized government tool in socialist Venezuela, allowing the state to take control of a private business if it is vital to the well-being of the population. But there is a process for this type of expropriation and del Gallego rarely followed it.

Instead, under her leadership, government officials abused their authority to confiscate businesses without due process or, alternatively, they used the threat of expropriation to extort business owners, according to PSUV insiders, members of the Zulia business community, and local officials and politicians.

“It was terrifying to work with Prieto in power,” a Zulia business leader told InSight Crime. “There were no small or big business, only the businesses or locations that Prieto wanted.”

InSight Crime heard about dozens of such cases, but the widespread perception that Prieto controlled the judicial system meant that almost no one reported the egregious abuse of power.

One notable exception was that of the pharmaceutical producer SM Pharma, whose founders, the Santamarta family, are currently seeking reparations for its illegal expropriation before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague.

Arbitration documents seen by InSight Crime paint a picture of government harassment and coercion that escalated until Prieto simply took the company by force on September 3, 2018.

Surrounded by members of his cabinet and armed forces led by Vílchez, Prieto dismissed the Santamartas along with the company’s other directors and key employees. He claimed to be executing an expropriation order, although Zulia’s legislative council only approved that order weeks later.

SM Pharma’s new board of directors was led William Cabello, as its president, and Flor Machado del Gallego, Rebeca’s daughter, as its general manager. This new directorship ran the company into the ground, leading first to the contamination of medicine and eventually a complete shut-down of production. The plant now lies in ruins, former PSUV insiders and sources in Zulia’s business community told InSight Crime.

Prieto’s Frontmen

Prieto’s inner circle extended beyond government offices to a small group of businessmen that made up his network in the private sector. These businessmen, known as Prieto’s testaferros, or frontmen, grew ostentatiously rich from the expropriation and destruction of their competitors.

Those favored by Prieto never faced extortion or expropriation. On the contrary, they enjoyed disproportionate access to state services and resources, like free gasoline, which benefited them directly and gave them an unfair and decisive advantage over their competitors. Sometimes they were simply handed expropriated businesses to run.

As grocery stores, hotels, ice cream shops, and cafes unaligned with Prieto’s administration shuttered, Prieto’s testaferros opened shiny new locations, buying infrastructure for cents on the dollar.

Prieto even handed one of his long-time testaferros, Danilo Nammour, the infrastructure for three large grocery stores that had belonged to private enterprise before being expropriated and run into the ground as a national government chain called Abastos Bicentenarios. When the national government liquidated the chain, Prieto made sure its three locations in Zulia went to Nammour.

They became La Grande, the grocery store chain of a man with no experience in food retail.

Prieto himself led the grand opening, bragging about the money spent on the revamp — almost 700 million bolivares, or around $8 million at that time, according to local media reports.

Soon after opening, La Grande came under fire for selling products at prices unattainable on a minimum Venezuelan salary, well above government standards and local market averages, and denominated in dollars, even before dollarization became widespread in Venezuela.

For many Zulia residents, La Grande and Nammour became symbols of the excesses of Prieto’s corruption. But he and Nammour were either unaware or unperturbed by this.

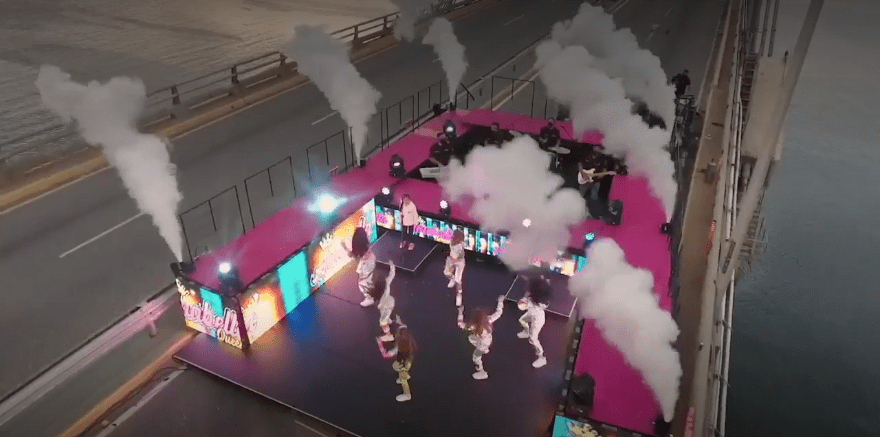

The profits from La Grande help fund Nammour’s extravagant lifestyle, which he continues to enjoy today. His Instagram is crammed with photos of the cars belonging to his personal racing team and, since 2018, he has been directing his pre-teen daughter’s pop music career under the stage name Anabella Queen and the tagline “pequeña gigante” (little giant).

Through no fault of her own, Anabella Queen has become a symbol of her father and Prieto’s brazen abuse of power.

In February 2021, as nearly 95% of Zulia’s population descended into poverty, Prieto and Nammour made headlines when Prieto closed the Rafael Urdaneta bridge for two days. They halted traffic across the state’s most vital transport artery so that Anabella Queen could put on a concert and record a music video. Nammour was the executive producer of the high-budget event, which according to its promotional material, was sponsored by multiple organizations, including the Zulia state government.

Nammour has made headlines for his ostentatious wealth, personal race car team, and shutting down the state’s biggest bridge to produce his daughter’s music video. Credit: @dnammour767 Instagram and Anabella Queen promotional material

The move caused outrage for its perceived arrogance. As one Zulia businessman put it, “Chávez himself could not close that bridge!”

Neither Prieto nor Nammour bothered to comment. Experience had repeatedly shown Prieto that the outrage of ordinary citizens need not be his concern. He could do whatever he wanted without having to worry about repercussions at home or from Caracas. Or so he thought.

PART 3

A Violent Last Stand

In March 2019, at the height of Venezuela’s economic and humanitarian crisis, chaos broke out in Zulia. As rolling blackouts plunged the state into darkness, desperate residents took to the streets rioting and looting in various cities over multiple days.

In many cases, security forces were slow to respond. In others, they never came at all.

“There was no call for calm, no action. We felt like there was no one to protect us,” Iraida Villasmil, the current president of Zulia’s legislative council told InSight Crime.

Business community leaders, even those who worked with Prieto’s administration, corroborate her recollection. And some believe that Prieto purposefully held the military back.

“They looted some businesses and not others. There was a pattern,” one business leader told InSight Crime.

While many were looted to destruction, businesses linked to Prieto seemed to be immune. In the aftermath of the attacks, they expanded into new locations, taking advantage of the real estate and infrastructure their bankrupt competitors were forced to sell cheaply. By the time Reverol and three other ministers arrived to restore order to Zulia, around 600 businesses had been affected, according to Venezuelan news media.

Prieto and his network seemed to be soaring as Venezuela collapsed around him. But he failed to see the signs that his days of unchecked excess were coming to an end.

Cracks Begin to Show

For Eduardo Labrador, the blackouts and lootings of 2019 were the final straw.

Tensions between Prieto and Labrador, by that time serving as a member of Zulia’s state legislature, had been building since Prieto’s first days as San Francisco’s mayor. Since then, Labrador had spent nearly a decade being progressively sidelined and ignored by his party, watching Prieto get away with violent and corrupt behavior that benefited him and his inner circle while bankrupting Zulia and the leftist project.

Less than a week after the riots, Labrador signed a declaration effectively denouncing not just Prieto but the whole Chavista system in Venezuela. The declaration, also signed by a former mayor of the municipality of Cabimas named Felix Bracho and two other representatives of Zulia’s state legislature, called on Maduro and the National Constituent Assembly to hold a national, non-binding no-confidence vote in which Venezuelans would decide whether or not to re-legitimize everyone in public office.

The timing was painful for the regime. The blackouts were just the most visible sign of Venezuela’s collapse, and the international community was already lining up to recognize Juan Guaidó, the young president of the sidelined National Assembly, as the legitimate president of Venezuela.

Labrador and his group further upset Maduro and his allies by publicly consulting with the European Union on the declaration, giving unwelcome legitimacy to foreign intervention in Venezuelan affairs. It made Maduro look weak and revealed that Prieto could not keep his party in line.

Sensing a threat, Prieto went on the offensive.

Labrador and his group were kicked out of the PSUV, and effectively out of the Legislative Council. Labrador was stripped of his position as a university professor. Then, in April 2019, authorities picked up Bracho and another member of the dissenting group.

Labrador went public, filing a legal suit accusing the authorities not only of violating Bracho’s human rights and rights to due process, but also of international conventions on torture.

“It was terrible what they did to Felix,” Labrador said. “They dragged him out of his house, beat him, put him on the back of a motorcycle, and took him to a military compound where the real torture began. There they simulated execution, suffocated him, doused him in cold water. In short, every torture you can think of.”

Labrador described how he and others campaigned for Bracho’s freedom for ten days before he was finally released. He said that he and Bracho immediately went into hiding.

“The moment we left military headquarters, the order came out to raid my house and the house of another colleague,” Labrador said. “I was not a criminal, did not steal anything, was not corrupt.”

Labrador and his colleagues had been too ambitious. They tried to take on the whole of the PSUV and were shut out. By April, they had joined the opposition, marking their final break not just from Prieto but from the whole Chavista political movement.

The dissenting group, whose support had once been vital to Prieto, was no longer relevant. Prieto had survived their rebellion. But the balance of power was beginning to shift against him.

A Divided Party

Though Prieto had bested Labrador and his group, their dissent had revealed the cracks in Prieto’s grip on Zulia. By the time the primary elections rolled around in 2021, other powerful PSUV rivals were ready to mount a challenge. Prieto, however, was prepared to fight back.

For as long as he was in power, Prieto had been resentful, impetuous, and aggressive against anyone he saw as a political threat. His disdain had alienated important PSUV figures in Zulia including the former Governor Francisco Arias Cárdenas and former Maracaibo Mayor Giancarlo Di Martino. Though Labrador’s rebellion had failed, these regional heavy hitters moved to capitalize on Prieto’s growing weakness.

While the president’s need to maintain his grip on power had protected Prieto and his network during the height of Maduro’s crisis years, by this time, Prieto’s gangster governor persona was also becoming increasingly at odds with the image of Venezuela that Maduro wanted to portray internationally.

“Omar’s not well-liked in Caracas. He overstepped the red line, passing the limit [of what was permissible],” Ricardo Acosta, the former president of Zulia’s Chamber of Commerce Federation, told InSight Crime.

SEE ALSO: GameChangers 2022: Maduro Seeks to Be Venezuela’s Criminal Kingmaker

With the election of President Joe Biden in 2020, Maduro saw an opening to reset his relationship with the United States and ease crippling international sanctions, which had increased during the first year of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

With the elections approaching, Biden’s administration was signaling its willingness to negotiate a softening of some of those sanctions — but only if Caracas cleaned up its act.

Meanwhile, Prieto’s popularity had plummeted in the wake of the 2019 blackouts. Crime and state violence had proliferated, and Prieto had made little effort to better his constituents’ lives through public works or social programs.

“He went from being a good mayor to a lousy governor,” the Prieto-linked political expert said.

Thus, Prieto arrived at the August 2021 PSUV primaries in a significantly weakened state. Arias Cárdenas and Di Martino chose this moment to act, joining forces to undermine Prieto’s political support ahead of the elections.

Prieto survived the political attack from within his party, managing to clinch the PSUV’s nomination. But the internal fracture split Zulia’s PSUV and shook Prieto’s confidence, according to the Prieto-linked political expert.

“It was an ugly internal fight. The world came down on Prieto,” he told InSight Crime.

Prieto began lashing out at his own party, rattling his base. Poll numbers began to show him losing the election.

“Prieto started to look lonely. His allies started to abandon him. That’s when he fell,” the Prieto-linked political expert said.

It seemed that while Caracas had allowed Prieto to run as the PSUV candidate, Maduro was not going to help him by deploying the tactics he had used previously, which had drawn international condemnation for election rigging. Not with the whole world watching.

Prieto pressed on with his election campaign, which promised public works and featured the images of famous Zulia artists, military leaders, and landmarks under the slogan “ZuliaMia,” or “My Zulia.” In the context of his floundering support and tanking poll numbers, the campaign began to take on an ominous tone.

As the November election grew closer, Prieto seemed to resign himself to the possibility that he would lose Zulia. But he remained unwilling to give up control of San Francisco, his hometown and the seat of his power.

“He had to win in San Francisco. That was his house,” a San Francisco political leader explained.

ZuliaMia

The violence started even before the November 21 elections. And it escalated as a desperate Prieto and his remaining allies made their last stand.

In the days leading up to the vote, opposition election workers preparing polling centers were targeted.

“They weren’t disguised, so I recognized the guys from San Francisco, the guys who worked for Prieto,” a San Francisco political leader who was followed and harassed in the lead-up to the elections told InSight Crime. “They were beating [election workers], snatching away their credentials, just not leaving them alone.”

Election morning began with reports of what Labrador called “death caravans” — trucks of armed men arriving at voting stations to intimidate voters, election officials, and journalists. From then on out, he said, “so many things went wrong at once.”

Around 7:00 a.m., Labrador started receiving harassing and threatening phone calls, and soon thereafter, he said, he realized he was being followed. By 9:00 a.m., when early morning polling data began to show that the opposition was doing well, the violence began in earnest.

Members of the opposition, the media, and regular voters in San Francisco said that plainclothes Polisur officers and known Prieto henchmen seemed to be everywhere. They harassed voting lines, the sources said, pacing up and down with bats and demanding to know how the people in the line were going to vote. At times, they beat people.

SEE ALSO: In Contested Zulia and Táchira, Violence Mars Venezuelan Elections

Anibal Riera, a journalist who was covering the elections, witnessed the violence firsthand.

“You know, Omar is a person who talks a lot about God, peace, the church, that stuff. But his actions say something different,” he told InSight Crime.

Labrador remembers pleading with Prieto’s people to stop, at one point writing in a WhatsApp message to a PSUV municipal official, “Brother, be careful with this stuff. The times are changing.”

To another one of his pleas, the official responded explicitly: “They can’t stop. We’re looking for votes.”

Exasperated, Labrador sent a final voice note to the official in San Francisco, claiming to have identified election attackers on video and threatening to expose them as Prieto’s men.

Labrador was bluffing, and the deceit would soon make him one of their victims.

Just shy of noon, Labrador went to the opposition campaign headquarters, where Prieto’s men had been harassing people throughout the day.

Shortly after he arrived, a group of men, hooded and armed, entered the campaign headquarters and started threatening those inside with weapons.

“They came in as if this was an armed robbery — a stick up. ‘Put the phones, the cameras and the computers on the table where I can see them!’” Labrador recalled.

Their demand for everyone to turn over their recording devices made Labrador realize that the men were there because of his empty threat to expose them with video footage of the attacks.

“Prepare yourself. They’ve come for me,” he remembers telling a nearby journalist.

Labrador also realized that while his original threat to expose them had been empty, this was his opportunity to make it real. He began filming the violence while trying to hide his phone.

“I thought ‘they are there to intimidate us, to scare us,’” he told InSight Crime, remembering how he goaded them. “They were armed, and I said, ‘Shoot! Shoot — You’re not going to shoot!’”

At first, he said, they looked scared. But then they saw that he was recording them.

“They realized that I had a phone, and they attacked. They hit me, they punched me. The blows kept coming — six, seven, eight punches. In the end, I needed seven stitches,” Labrador said.

After the beating, the journalist who had been standing next to Labrador reappeared, shaken.

It was then that he told the journalist to film him bloody and denouncing election violence, a scene that would soon be broadcast on news stations and circulating on social media across the country.

He also sent the video to Prieto’s old ally General Rengifo, who, as head of the top military command in Zulia, was responsible for maintaining order and security during the elections.

Although the video failed to load and send, it was only the last in a series of messages Labrador sent Rengifo that day, which escalated in their desperation. The last one, sent at 1:36 p.m. read: “Stop this General. These people are going to kill someone in San Francisco.”

Labrador could see that Rengifo had read the messages, but the general did not respond.

In fact, his warning would have come too late even if Rengifo had been willing to intervene. Around mid-day, armed men allegedly answering to Prieto had attacked a voting line outside a San Francisco school, firing into the crowd and killing a local voter.

The killing, along with Labrador’s video, made headlines, and the chaos in Zulia was described as an embarrassing outlier in Venezuela’s otherwise peaceful elections.

Yet despite the election violence, the PSUV lost in Zulia. Prieto lost the governor’s seat and the party lost 15 of Zulia’s 21 municipal mayorships to the opposition, including the capital Maracaibo and Prieto’s own beloved San Francisco.

Watch and share InSight Crime’s video explaining how election day violence unfolded over the course of November 21.

An Overstayed Welcome

Though he lost Zulia, Prieto refused to give up. The ousted governor undermined the handover of power at every turn. Even today, he maintains some influence over the state’s economic, political, and security sectors.

The new opposition governor, Manuel Rosales, officially took office in December 2021, but Prieto’s people resisted the transition. InSight Crime spoke to numerous sources with intimate knowledge of the matter, but most did not want to be quoted, even anonymously, out of fear for their personal safety or of political repercussions.

SEE ALSO: A Seat at the Table: What New Governors in Venezuela Mean for Organized Crime

One source claimed that the majority of the state institutions that were supposed to pass to opposition control were not turned over after the election. Rosales did not gain control of the police until the end of January 2022 and for other government departments, the process took even longer.

Multiple sources described how members of the new administration had to identify, locate, and compel Prieto’s administration to turn over government infrastructure, like buildings, computers, and cars, sometimes by force. Some remain in the hands of Prieto’s people.

Rebeca del Gallego turned over the prosecutor’s office, but the building was wrecked, computers were stolen, and many important case files were either missing or destroyed, a well-placed source told InSight Crime.

The process of “forced transition” was still ongoing in January 2023, when InSight Crime visited Zulia. At that time, Prieto’s people continued to drive vehicles, live in apartments, and profit from businesses that belonged to the state, the sources reported.

Not only that, but some of Prieto’s people continued to hold government and security positions.

“He still has power because his people are still in positions of power, even in the police,” the former security official with connections among active intelligence forces told InSight Crime.

Gen. Rengifo, who had refused to answer Labrador’s pleas for help on election day, was promoted to the head of military command for the whole of the Andes region in July 2022. Today, he oversees the states of Mérida, Táchira, and Trujillo.

A Possible Comeback

At first, Prieto disappeared from the public eye. Rumors swirled that he had been arrested and was on the verge of being charged with embezzlement and gross misuse of government resources.

Instead, in April 2022, Prieto’s social media came alive, and a new kind of rumor began to swirl: that Prieto was gearing up for a political return and that the PSUV would allow it.

Whispers circulated that while the PSUV would not let Prieto have another run for governor, they would allow him to return to power as the mayor of San Francisco. Those whispers multiplied and gained substance as Prieto started taking higher-level political meetings towards the end of 2022.

Some, including Labrador, refuse to entertain a future with Prieto back in power.

Yet, while a return for Prieto once seemed unthinkable, it now looks like a real possibility. Negotiations between the Maduro regime and the opposition, which were supposed to include measures to guarantee free and fair elections in 2024, have recently stalled, while political violence by pro-regime armed groups is on the rise.

And while Prieto has not publicly announced his intention to run, in a speech he made when leaving office, he hinted at his thinking, saying, “There will be new opportunities, new battles and then, we will be ready.”

InSight Crime attempted to contact all the people named in this story by email, phone, or through social media networks to give them the opportunity to respond to the accusations in this story. In the case of Luis Curiel and Omar Barrios, reporters were unable to make contact. By the time of publication, Pedro Carreño was the only person to respond.