La Unión Tepito is a cell-based criminal organization in Mexico City, named after one of the capital’s largest neighborhoods. It is currently one of the city’s main criminal players, funding itself from microtrafficking, human trafficking and extortion.

However, it has recently found its dominance seriously contested by both a targeted law enforcement crackdown and the incursion of larger Mexican cartels.

History

From the 1990s to the early 2010s, the leading gang in Mexico City was the Tepito Cartel, who rose to power using their ties to the Beltran Leyva Organization (BLO) and its chief enforcer Edgar Valdes Villareal, alias “La Barbie.” The BLO’s decline in the late 2000s, however, led to a concurrent loss in status for the Tepito Cartel, inviting the arrival of competing groups, such as La Unión Tepito.

Formed between 2009 and 2012 by defectors from declining groups such as the BLO and Familia Michoacána, possibly on the initiative of Valdes Villareal, La Unión Tepito quickly challenged the Tepito Cartel for control over both the Tepito neighborhood and large parts of Mexico City, using targeted acts of violence to assert its dominance and push out other groups, including cells of large national organizations like Los Zetas and the Sinaloa Cartel.

In October 2012, six local drug retailers believed to have worked for the Sinaloa Cartel were executed in the street. In May 2013, 12 people were kidnapped from a bar in Mexico City’s Zona Rosa, including relatives of Tepito Cartel leaders. In both cases, La Unión Tepito was blamed. By the end of the ensuing gang war, La Unión Tepito was the predominant criminal force in Mexico City.

Besides taking over drug retail spots across Mexico City, including Tepito itself, La Unión began extorting local businesses, often using the “gota a gota,” or “drop by drop,” method of offering high-interest loans to small business owners and street vendors with the threat of physical violence for those who could not pay.

Taking over the center of the capital meant access to not just shops and street vendors, but also bars and nightclubs. Extorting these businesses was particularly profitable, allowing drug retailers to operate inside and forcibly recruit employees as dealers or lookouts. La Unión Tepito also developed ties to local police, granting the group a measure of impunity and forewarning with regard to law enforcement action.

By 2017, however, another criminal entity would emerge named the Fuerza Anti-Unión, which would challenge La Unión’s dominance. Two theories exist about the Fuerza Anti-Unión: that they either arose as a vigilante group formed by business owners to combat La Unión’s extortion or as a splinter group from La Unión Tepito itself.

The latter theory is held by Antonio Nieto, a Mexico City journalist and author of a book on La Unión Tepito, who says the Fuerza Anti-Unión were not created as a criminal group per se, but rather as a temporary hit squad founded by one capo of La Unión Tepito, alias “El Tortas,” to avenge his brother’s death at the hands of another capo, alias “El Betito.”

However, most Mexican media framed the Fuerza Anti-Unión as a rival crime group, who reportedly established close relations with high-ranking members of Mexico City’s Secretariat of Security and Civilian Protection (Secretaría de Seguridad Ciudadana – SSC) while violently competing to control the city’s drug retail and extortion economies, particularly in the municipalities of Álvaro Obregón, Tlalpan and Cuauhtémoc.

In June 2018, two dismembered bodies and a “narco-manta” (narco-banner) were found on Mexico City’s bustling Avenida Insurgentes, with a message from La Unión Tepito threatening the Fuerza Anti-Unión leader. It was only the most visible manifestation of a surge in violence that month, confirmed by Mexico City’s head of government José Ramón Amieva to be caused by clashes between the two groups.

La Unión Tepito remained stronger than its rivals, however, expanding its extortion operations into wealthier parts of the city where it could demand higher amounts, sometimes up to 50,000 pesos a week (around $2,600). In April 2019, hundreds of local shopkeepers signed a letter pleading for Mexico City authorities to take action against La Unión, with the leader of the association warning shopkeepers might be forced to form a self-defense group if nothing was done. One week later, he was shot seven times by armed men and killed.

In October 2019, a police raid captured 31 Unión members and uncovered two synthetic drug laboratories. The raid was triggered by reports of collusion between gang members and city authorities, according to Mexico City Security Secretary Omar García Harfuch, who claimed to have a list of around 120 police officers that may have collaborated with La Unión. Though 27 of those captured were later released, it did mark a turning point in La Unión’s fortunes.

Since then, it has had to contend with the increased presence in Mexico City of the country’s two biggest crime groups, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG) and, more recently and to a lesser extent, the Sinaloa Cartel (Cartel de Sinaloa).

By 2020, the CJNG had come to supply microtraffickers with drugs in nine of Mexico City’s 16 districts, with CJNG members directly extorting businesses in the Historic Center, long a key Unión Tepito territory, and the new Fuerza Anti-Unión leader reportedly maintaining strong ties with the CJNG, including being supplied with drugs, arms and hitmen to wage its war against La Unión Tepito.

Yet the CJNG’s Mexico City campaign appears to have slowed, with the cartel struggling to establish stable territorial control, and the Sinaloa Cartel appears to have limited itself to despatching envoys to the capital to try to increase its involvement in the lucrative drug consumption market.

La Unión Tepito’s more pressing concern has therefore come from Mexico City law enforcement, who have deployed a relentless crackdown against it, freezing roughly $5.2 million across 1500 Unión Tepito-linked bank accounts and arresting some 550 of its members from January 2020 to April 2022, a greater number than those from the next ten local crime groups combined.

As a result, in February 2022, Mexico City’s Secretary of Citizen Security Omar García Harfuch declared La Unión Tepito had been irreparably fragmented, claiming the group’s prioritized targeting and its leader’s arrest in early 2020 meant the gang’s remaining cells now operated in isolation, independently of central command.

Leadership

As of May 2022, La Unión Tepito’s most commonly cited leader continues to be Rául Rojas Molina, alias “El Mi Jefe.”

A key lieutenant of one of La Unión’s former leaders, Roberto Moyado Esparza (a.k.a.“El Betito”), who was arrested in 2018, Rojas Molina has climbed the ranks since his incarceration in 2010 for armed robbery and crimes against public health and is currently linked to 38 homicides, 18 of which he allegedly carried out.

He has taken over since the May 2020 arrest of leader Brandon Alexis Flores, alias “El Junior,” brother of Oscar Andrés, alias “El Lunares,” who was leader until his arrest in January 2020. Rojas Molina’s two closest subordinates are thought to be known as “El Manzanas” and “El Elvis,” respectively in charge of La Unión’s extortion and microtrafficking operations.

However, as of 2022, the group’s continued targeting by law enforcement has meant La Unión Tepito is no longer a single hierarchical organization, but rather a series of connected cells, each with its own leader, territory and particular criminal activity. Media reports suggest there are now at least five major factions, with many more smaller cells.

Geography

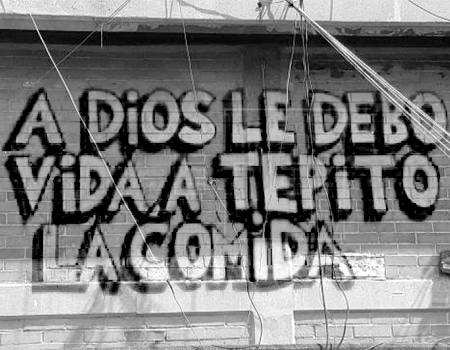

La Unión Tepito is a highly localized criminal group, deriving its power from the social and even familial bonds it shares with certain Mexico City communities. Besides its heartland in the rough and central neighborhood of Tepito, it retains some sort of presence in all of Mexico City’s 16 districts, with a strong presence in the districts of Cuauhtémoc, Iztapalapa, Benito Juárez, Miguel Hidalgo and Venustiano Carranza, particularly in the Historic Centre and Zona Rosa.

Outside of Mexico City, the group maintains lower-scale micro-trafficking and sometimes extortion operations in surrounding states, such as Hidalgo, Querétaro, Tlaxcala, Puebla, Veracruz and the State of Mexico.

Allies and Enemies

Despite being initially formed by defectors of several crime groups, La Unión Tepito has many enemies and few allies. It has long fended off competition from the smaller Mexico City gangs, such as the Tláhuac Cartel, the Rodolfos and more recently Lenin Canchola, who seek to wrest away a larger share of the city’s microtrafficking and extortion economies.

Then in 2020, reports suggested the CJNG was directly sending men to take over key Unión territory in Mexico City. According to Óscar Balderas, a Mexican journalist and expert in organized crime, “the CJNG has an aggressive expansion plan that requires controlling the points that La Unión Tepito has today, such as the walking corridor behind the National Palace, the areas of La Merced, Mixcalco and Lagunilla.”

The same year, drug tunnels were discovered under the Central de Abastos, Mexico’s largest market, allegedly operated by the Fuerza Anti-Unión with CJNG support. The former had reportedly installed 50 members in the market to control drug sales and extortion rackets, thereby challenging La Unión’s control of this important economic and criminal hub.

Furthermore, the CJNG is reportedly arming not just the Fuerza Anti-Unión, but also some of the city’s gangs in their fight against La Unión Tepito, most notably the Tláhuac Cartel. There are also signs both main factions of the Sinaloa Cartel are making moves into the capital.

Prospects

La Unión Tepito faces an uncertain future, one which has divided expert opinion. Some believe it will inevitably decline; others, that it will survive and evolve.

Besides competition from local rivals and national cartels, the localized nature of the extortion and microtrafficking rents La Unión Tepito depends on makes it inherently vulnerable to the kind of atomization inflicted upon the group by law enforcement operations.

On the other side, however, are those that argue that even if authorities were not overstating the crackdown’s impact on La Unión Tepito, its loss of centralized leadership is not an existential threat.

For now, its dominant cells are not clashing with one another and can effectively repel the advance of local rivals, while neither the CJNG nor the Sinaloa Cartel have the firepower or inclination to take on the organization in a street-by-street shooting war across Mexico City.