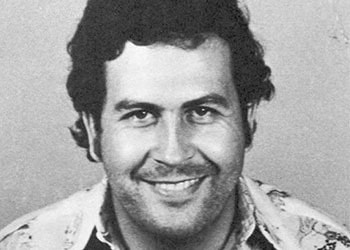

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was the pioneer in industrial-scale cocaine trafficking. Known as “El Patrón,” Escobar led the Medellín Cartel from the 1970s to the early 1990s. He oversaw each step of cocaine production, from sourcing coca base paste in Andean nations to feeding a booming US market for the drug. He also successfully challenged the State on extradition, showing that extreme violence could force governments to negotiate.

History

Like most of his partners in the Medellín Cartel, Escobar came from a humble social background. He dropped out of school because his family could not pay for his education and soon got involved in petty crime. His early criminal activities included smuggling stereo equipment and stealing tombstones to resell them.

Escobar then entered the cocaine trade, founding the Medellín Cartel in the 1970s and the Ochoa Vásquez brothers (Jorge Luis, Juan David and Fabio). The Ochoa brothers were initially the business brains of the outfit. Meanwhile, Escobar first oversaw the group’s “protection” before emerging as its undisputed leader.

During the Medellín Cartel’s zenith in the 1980s and early 1990s, Escobar controlled nearly the entire cocaine supply chain. He oversaw the import of large, multi-ton shipments of coca base from Andean nations Peru and Bolivia into Colombia, where it was processed into cocaine in jungle labs. The criminal enterprise then stored the drug in Colombia before flying it to the United States. In the 1980s, the organization is estimated to have supplied over 80 percent of all cocaine shipped to the country, sending across some 15 tons per day.

In this period, kidnappings made by guerrilla groups led the State to collaborate with criminal groups. The 1981 kidnapping of the sister of the Ochoas led to the creation of a Medellín Cartel-funded paramilitary group known as Death to Kidnappers (Muerte a Secuestradores – MAS).

In the mid-1980s, Escobar’s hold on Medellín increased when he founded a criminal debt collection service known as the “Oficina de Envigado.” This was an office in the town hall of Envigado, a small municipality next to Medellín where Escobar grew up. Escobar used the municipal office to collect debts owed to him by drug traffickers and set the “sicarios” or hired killers on those who refused.

Unlike many drug traffickers today, Escobar was not afraid to flaunt his riches. His cartel is estimated to have earned around $420 million in revenue per week during the mid-1980s, and Escobar himself made Forbes’ Billionaires list for seven years straight, between 1987 to 1993. His luxurious multimillion-dollar “Hacienda Nápoles” estate had its own zoo, and he reportedly ate from solid gold dinner sets.

Despite his opulent lifestyle, Escobar presented himself as a populist figure, persecuted by the upper classes for his own social background and efforts to help the poor. He attempted to stir up anti-establishment sentiment and win over disadvantaged communities by opening a public zoo, constructing 70 community soccer fields and building housing for the poor.

He could not break into Medellín’s upper social classes, which blocked his application to join the city’s top social club. His attempts to join the political elite were also crushed in the early 1980s when he was expelled from Colombia’s Liberal Party and thrown out of his position as a deputy congressman.

These tensions escalated in the mid-1980s when the Medellín Cartel declared war on the Colombian state. In April 1984, the nation’s then Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla was shot dead by sicarios working for Escobar. The Colombian state responded by immediately signing into law Escobar’s extradition to the United States. In response, Escobar’s hitmen murdered dozens of judges, police and several journalists in the late 1980s. During the 1989 presidential elections, Escobar’s assassins murdered the Liberal Party candidate Luis Carlos Galán Sarmiento. They then made a failed attempt to kill Galán’s replacement, Liberal Party presidential candidate César Augusto Gaviria Trujillo.

Using these tactics, Escobar eventually pushed the State to ban the extradition of Colombian nationals in the 1991 Constitutional Assembly. He managed to negotiate his surrender to authorities and took up residence in a jail known as the “Cathedral,” which he built. It was a jail only in name. Escobar controlled the guards and had a playhouse built on the grounds for when his daughter went to visit. He used his first year behind bars to reorganize the Medellín Cartel.

But his influence in the organization was dwindling. Resentment against Escobar grew when he raised a “tax” on cartel members, making them pay between $200,000 and $1 million in fees.

And in July 1992, Escobar’s men found a stash of $20 million on a property belonging to cartel member Fernando Galeano. Escobar summoned Galeano and another associate, Gerardo Moncada, for a meeting at the Cathedral. Both were then killed by two of Escobar’s sicarios.

On hearing of the killings, President César Gaviria ordered for Escobar to be sent from the Cathedral to a military base in Colombia’s capital, Bogotá. Before he could be transferred, Escobar escaped.

Ultimately, Escobar’s former criminal associates teamed up with the government and gradually dismantled his empire. Out of money, luck, and with just one bodyguard left, authorities in Colombia gunned down Escobar on the rooftop of a house in Medellín on December 2, 1993.

Rumors have circulated for years around his death. Former paramilitary leader and mafia boss Diego Fernando Murillo Bejarano, alias “Don Berna,” claimed his brother fired Escobar’s shot.

Criminal Activity

Escobar was instrumental in setting up the Medellín Cartel, feeding booming demand in the United States during the 1980s.

Through the 1980s and early 1990s, Escobar oversaw each step of the cocaine supply chain as the Medellín Cartel’s undisputed leader. The organization sourced coca leaf from primary production points in Peru and Bolivia, processed it in Colombian jungle labs, then shipped cocaine to the United States, where operatives sold it on the streets.

He focused on international markets for cocaine and never sold the drug domestically to Colombians for consumption. Instead, Escobar initially used a Caribbean air route to feed the US market.

Escobar also ordered contract killings to target police, judges, politicians and journalists. On the other hand, the Medellín Cartel maintained high-level allies in security and justice institutions that largely protected its members from prosecution.

He dipped into extortion, too. While he was at the “Cathedral,” he made his money by shaking down other drug traffickers, who had to pay him a fixed sum every month.

Finally, Escobar was known for investing profits from the drug trade in luxury goods, property, and works of art. He is also reported to have stashed his cash in “hidden coves,” allegedly burying it on his farms and under floors in many of his houses.

Geography

Escobar headed the Medellín Cartel, named after the Colombian city where it was based. However, his influence extended to as far as the United States, where he ran distribution networks.

Medellín has paid a high cost in blood for its role in the international cocaine trade. The city’s murder rate was the highest in the world during Escobar’s day.

To ensure the smooth transfer of cocaine from coca leaf to consumer, Escobar’s ties extended to Andean production nations (including Bolivia, Peru) and the United States and Canada.

He also sought refuge in Panama – a nation the Medellín Cartel appears to have passed drugs en route to the United States – when Colombian authorities attempted to capture him.

Allies and Enemies

Escobar’s success in the underworld relied on alliances far and wide. His actions, wealth and public profile also meant he had many enemies, whose eventual alliance would ultimately lead to his downfall.

The Ochoa Vásquez brothers (Jorge Luis, Juan David and Fabio) were close allies of Escobar for years. They helped form the Medellín Cartel and worked for hand in hand with the drug lord to run the organization. Others, such as José Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha, alias “El Mexicano,” also worked with Escobar to provide the organization with muscle and logistical support.

Escobar also maintained alliances with associates based in Andean production nations. Jorge Roca Suárez, alias “Techo de Paja,” was identified as having provided cocaine shipments to Escobar and his uncle Roberto Suárez Gómez, known as the “King of Cocaine” in Bolivia.

The Medellín Cartel also formed alliances with Mexican groups to traffic cocaine into the United States. Escobar allied with leader of the Juárez Cartel, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, alias “El Señor de los Cielos,” or “Lord of the Skies.” Carrillo Fuentes used his fleet of aircraft to transport drugs belonging to Escobar as part of the Guadalajara Cartel.

One of Escobar’s most consistent enemies was the Cali Cartel. The Cali Cartelinitially cooperated with the Medellín Cartel during the early 1980s to stabilize the drug market and divide territory in the United States. However, by 1988 the cartels were fighting a vicious turf war in Colombia.

The Cali Cartel ultimately funded elements of the Medellín Cartel that turned against Escobar after the 1992 murders of Galeano and Moncada in the Cathedral. They attacked Escobar’s support structure by calling themselves the People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar (Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar – PEPES. One Cali Cartel leader, Francisco Hélmer Herrera Buitrago, alias “Pacho,” claimed that he personally invested $30 million in the war against Escobar. The PEPES’ principal objective was to hunt down Escobar. The PEPES worked with and were protected by the State.

PEPES membership included the founders of what became the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC): the brothers Fidel Antonio Castaño Gil, alias “Rambo,” Carlos Castaño Gil, and José Vicente Castaño Gil, alias “El Profe,” as well as “Don Berna,” who joined the AUC later.

Former allies of Escobar, the Castaños grew distant from him for many reasons. These included his stated affinity for left-wing guerrillas, his alleged links to the M-19 rebel movement and the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN).

Meanwhile, Don Berna turned on Escobar after El Patrón killed his boss, Fernando Galeano. Don Berna and his PEPES associates tracked down Escobar’s family and connections, killing many of them. The police used Don Berna for information, leading to the capture of several Escobar associates, seizure of properties, and freezing his bank accounts. Don Berna claimed he and other members of PEPES were with the police that located Escobar on the day of his death.

To bring down Escobar, the PEPES worked alongside the Search Bloc, an elite police unit formed in 1989 made up of around 600 members and based out of the Carlos Holguín Police School in Medellín. When Escobar surrendered in 1991, its members were dispersed. It reformed following his escape from prison in 1992 and hunted him until his death in 1993.

Legacy and Influence

Escobar’s death signaled the end of one era of drug trafficking and the birth of another. Mystique surrounding the drug lord has grown since 1993, and endless myths have circulated.

The Medellín Cartel no longer exists, nor does the cartel structure Escobar help to found, which involved controlling all the links in the drug chain from production to retail.

While the Colombian department of Antioquia, of which Medellín is the capital, remains pivotal to the nation’s cocaine trade, today’s drug lords bear little resemblance to Escobar.

Following Escobar’s downfall, the structure of Colombia’s underworld — and Medellín’s especially – shifted. It gradually went from being hierarchical and dominated by a few key actors to more federal, fragmented and horizontal. The “Oficina” – which had its roots in Envigado – transformed into a mafia federation that now regulates almost all criminal activity in Medellín.

A modern-day counterpart to Escobar himself is hard to come by. There is no single figure able to exercise control even in Medellín today, let alone over a large portion of the international cocaine trade. Instead, a given figure climbs up the ladder, is often quickly identified by authorities and captured. Today, Escobar’s closest counterparts would be the Mexican capos.

Since Escobar, a new generation of “Invisible” traffickers has emerged. They have learned that demonstrating a luxury lifestyle and using extreme public violence is counterproductive. Instead, anonymity is their protection plan. This new generation of drug traffickers looks like young entrepreneurs or highly qualified businessmen. They are unrecognizable from those who dominated in Escobar’s day.

With this, the “man of the people” model traffickers like Escobar traditionally tried to transmit is dying out. Mexican trafficker Joaquín Guzmán Loera, alias “El Chapo” operated using this approach and Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, alias “El Mencho” has replicated it to a certain extent. But now, criminal governance and loyalty are largely being cultivated at the group level, not by individual leaders.

Escobar achieved a level of state penetration which helped members of his cartel to avoid capture for years. The fact he was elected to Congress as an alternate tells us about how deeply he could achieve this.

Drug traffickers still have links to state institutions. Political elites have been historically linked to drug trafficking and corruption. Other institutions continue to be penetrated at a more local level. The Urabeños, one of Colombia’s most influential criminal groups, for example, have worked through corruption networks linked to local governments in Colombia.

The US Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act may also be considered as another legacy of Escobar’s influence. Made law in 1999, it permits “the identification of and worldwide sanctions against foreign narcotics traffickers whose activities threaten US security, foreign policy, or the economy.” Its purpose is to prevent foreign drug traffickers from trading with US companies or individuals.

Finally, Escobar remains a contemporary narcoculture symbol, the “kingpin” in the popular imagination. His name is often used to refer to drug lords that have cornered the drug market in certain Latin American countries. However, few – if any – have ever built a cocaine empire to rival Escobar, who continues to inspire numerous books and television shows, with his face even stamped on to drug packets.