Honduran President Xiomara Castro unveiled a raft of “radical actions” the government intends to implement to tackle organized crime in an announcement that captured headlines but added little substance to Honduras’ flailing crime strategy.

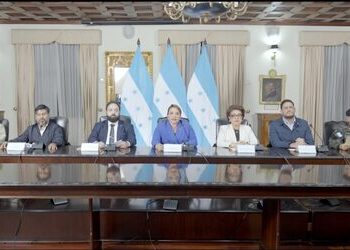

In a June 15-televised press conference, Castro, who was flanked by members of the National Defense and Security Council (CNDS), urged the security forces to immediately “execute urgent interventions” in municipalities with a high crime incidence.

Members of the Council then took turns to read fourteen measures from a three-page document titled “The Radical Actions of the Solution Plan Against Crime.”

SEE ALSO: Honduras and El Salvador: Two States of Emergency With Very Different Results

The most eye-opening was the proposed construction of a prison with a capacity of 20,000 between the eastern departments of Olancho and Gracias a Dios, long-time bastions of organized crime and violence.

The announcement echoed the launch of Honduras’ state of emergency in November 2022 when the government first partially suspended constitutional rights, ostensibly to give security forces the necessary powers to crack-down on extortion and violence.

Originally planned for 45 days in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, Honduras’ capital and second-largest city, the government has repeatedly renewed and expanded the state of emergency. The measures are now in force in 226 of the country’s 298 municipalities and affect over 90% of the country’s population.

State authorities maintain that the state of emergency has been highly successful in combating crime, often crediting it for achieving security results, even in municipalities where the measures are not technically being implemented.

“The declaration of the state of emergency … has allowed the National Police … to achieve significant improvements in the security of our country,” Castro declared on June 13.

Congress’ President Luis Redondo went further, suggesting that anybody opposed to the government’s crime strategies had links to organized crime themselves. In a post on X, he said that Hondurans “should not listen” to anyone opposing the government’s crime plan.

InSight Crime Analysis

The Security Council’s new measures indicate that the government is doubling down on what critics say is a chaotic mano dura that favors rule by emergency decree over long-term policymaking and has yet to show results.

“It’s a communication style where you try to communicate that you have a plan, but you don’t really have a plan,” Andreas Daugaard, Research Coordinator at the Association for a More Just Society (La Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa – ASJ) told InSight Crime.

The crimes the government said it was targeting have also continued apace. Although the government billed the original decree as part of an attempt to tackle extortion, the percentage of households affected by extortion in the country has actually increased from 9% to 11.3%, according to a report from ASJ.

SEE ALSO: Honduras Anti-Gang Crackdown Targets Only One Source of Violence

What’s more, several extensions of the state of emergency were not ratified by Congress, something that is jeopardizing prosecutions and potentially allowing criminals to evade justice. Just eight people were convicted of extortion in the first three months of 2024, according to the report, compared to 105 for the entirety of 2022.

“Honduras has rarely had so few people tried for extortion,” said Daugaard, adding that there were prosecutions that had been scuppered because lawyers representing the detained had successfully argued that the state of emergency was illegal.

And while homicide rates in Honduras have fallen in recent months, declines were recorded in both municipalities subject to the state of emergency and those that were not, undermining the government’s repeated claims that security gains are dependent on the suspension of constitutional rights.

An official with knowledge of the judiciary, who wished to remain anonymous because the person was not authorized to speak to the press, told InSight Crime that the state’s ability to create long-term security policies was jeopardized because key institutions, including the judiciary and the police, remained “captured and weakened” by organized criminal groups.

“Elements within the police play an important role in criminal groups and not just gangs,” the official said. “The main impact of the state of emergency has been the violation of society’s fundamental rights.”

In Rivera Hernández, a community in San Pedro Sula where several gangs are locked in an ongoing territorial conflict driven by extortion revenues, community leader Daniel Pacheco told InSight Crime that the state of emergency had “no impact” on the way criminal groups – including the fearsome gangs, the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and the Barrio 18 – operated inside the neighborhood.

Many police officers were reluctant to enter the area, according to Pacheco, preferring to remain on the main roads on the outskirts of the community. And while many officers were good, Pacheco said corruption within the ranks blunted their overall effectiveness.

“We’ve had complaints from transport sector workers that [police officers] demand extortion payments,” Pacheco told InSight Crime. “Criminal groups don’t feel any oppression from the state … No strategy will ever work [in Rivera Hernández] without first addressing corruption.”

Pacheco added that there had been a spike in kidnappings in Rivera Hernández, though security authorities had so far been unable to help. Last week, he recounted, a family was left negotiating with a gang for access to the body of a disappeared relative.

“It’s clear that the Minister of Security doesn’t understand what happens in these barrios,” Pacheco concluded. “The authorities keep saying they’ve had huge successes [but criminal groups] continue doing what they’ve always done.”

The official consulted by InSight Crime described the government’s crime strategy as superficial and added that while the creation of an effective long-term crime strategy was possible, it would not be easy.

“It would need to address crime prevention, prosecution, and social reintegration,” the person said. “The government’s neglect of social programs is a problem – organized crime takes advantage of vulnerable people.”

*InSight Crime contacted the Ministry of Security for comment but received no response by the time of publication.

Feature image: A screengrab from the televised press release shows Honduran President Xiomara Castro and members of the National Defense and Security Council. Source: Secretaría de Prensa Honduras