In 2021, Mexican authorities captured an Asian-Mexican businessman at a Mexican port and seized 23 tons of drugs. The shipping manifest said the businessman was importing “calcium chloride,” but lab results later showed that part of the cargo was fentanyl, the deadly synthetic opioid responsible for tens of thousands of overdoses per year in North America.

Authorities said they also found cocaine, marijuana, and methamphetamine, as well as other types of unspecified items. And although they did not disclose the amount of each drug they seized, investigators from Mexico’s Financial Intelligence Unit (Unidad de Inteligencia Financiera – UIF) said the network included the businessman, his wife, his daughter, and a series of associates spread across a wide geographic swath.

The businessman was part-owner of a women’s handbag company, as well as two other companies, which the UIF identified simply as company X and company Y. Red flags went up because the handbag company had no employees on its payroll, and between 2015 and 2016, it registered close to $140,000 in deposits, 98% of which were connected to currency exchange operations.

*This article is part of a two-year investigation that tracked the supply chain of precursor chemicals that aid in the production of methamphetamine and fentanyl in Mexico. Read the other articles of the investigation here and the full report here.

Intrigued, the UIF dug further and found that the handbag company had also “coordinated the shipment” of 16 tons of precursor chemicals to an “agro-industrial company.” The agro-industrial company, they found, had three owners, who the UIF believed were front-people working directly with the Asian-Mexican businessman.

In all, the UIF tracked hundreds of check and cash deposits, as well as hundreds of withdrawals and transfers among and between these different companies in what authorities believed was an effort to shield their illicit imports and launder their proceeds.

Eventually, they filed charges against the trafficker, his wife, his daughter, and the three third-party owners of the agro-industrial company. They also shut down the companies and seized the assets of 51 bank accounts associated with them.

This should have been a landmark case in Mexico. The problem was that the case was not real. It was part of a case-study, or what they called a “typology,” that the UIF was using to illustrate money laundering related to the synthetic drug industry.

The irony is that — while this case appears to be based, at least in part, on a real investigation — Mexican authorities have never identified any money laundering cases related to synthetic drugs or precursors in Mexico, according to our public records requests and interviews with officials. Nor were there any cases that had led to asset seizures or forfeitures.

“I checked everything,” a source in the Attorney General’s Office told InSight Crime in a text message. “There is not a single case.”

On one level, the dearth of cases is stunning. The United States has been pressuring Mexico to focus more on slowing the flow of illicit synthetic drugs, above all fentanyl. And targeting the flow of money to pay for precursors, as well as the proceeds that synthetic drugs generate, would appear to be an important priority for US investigators, especially given the drug flows emanating from China, the world’s preeminent chemical supplier. Since 2008, the United States has spent over $3 billion in training and equipping Mexican authorities, including helping to stand up the UIF.

But on another level, it has become commonplace for the current Mexican government to downplay the impact of synthetic drugs at home and abroad. While the Attorney General’s Office has publicly recognized the problem, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and the head of the Ministry of Public Security have consistently denied that fentanyl is produced clandestinely in Mexico, despite ample evidence to suggest otherwise. The government has also downplayed the rising use of synthetic drugs in Mexico, particularly methamphetamine, but also fentanyl.

That attitude seems to have permeated other institutions. In its most recent annual risk report — issued in November 2023 — the Finance Ministry did not highlight any concern regarding the flow of money for precursors, fentanyl, or methamphetamine, or the proceeds obtained therein.

It was as if the problem did not exist.

Don’t Follow the Money

It is an overused axiom to say authorities should follow the money. However, the money, in the case of precursor chemicals, is relatively small.

InSight Crime estimates that synthetic drug manufacturers in Mexico produce a maximum of 4.5 tons of pure fentanyl every given year, and a maximum of 434 tons of methamphetamine to meet the demand of the US consumption market. Based on our interviews with fentanyl and methamphetamine producers in Sinaloa and Michoacán, we estimate that the costs of the chemical substances required to produce these quantities run between $9 million and $22.5 million for fentanyl, and between $83.3 million and $126.5 million for methamphetamine.

Net earnings from synthetic drug sales are also relatively small. InSight Crime estimates the wholesale market for fentanyl in Mexico is between $15.7 million and $40.5 million; the wholesale market for methamphetamine in Mexico is closer to $330 million. Once these drugs cross the border, the prices go up significantly — between $27 million and $67.5 million for the US wholesale fentanyl market; and up to $1 billion for the US methamphetamine wholesale market — but not in relative terms compared to other criminal markets. For example, Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Sistema Nacional de Información Estadística y Geográfica — INEGI) estimates that corruption in Mexico is worth some $700 million. And Global Financial Integrity says criminal activity of all types in Mexico could be worth as much as $62 billion, of which $44 billion may be laundered in Mexico.

Even if Mexico wanted to pursue that $44 billion, it would be difficult. Few governments have the capacity, resources, and stamina to actually do these types of investigations. Even in the United States, where the axiom regarding following the money has been ground to dust, money laundering is not prosecuted often and when it is, few of these cases are related to drug trafficking.

In 2022, the last year for which there is data, the US Sentencing Commission said the US federal courts had prosecuted 1,001 individuals for money laundering. But just 17% of these individuals were charged for laundering proceeds earned from “controlled substances, violence, weapons, national security, or the sexual exploitation of a minor.”

Even big cases that get prosecuted seem to fizzle. In March 2010, Wachovia Bank, which Wells Fargo had recently acquired, paid the federal government a $160 million fine for potentially laundering a staggering $420 billion in drug trafficking proceeds from Mexico through currency exchange centers between 2003 and 2008. But no one from the bank was prosecuted.

In 2012, the US government levied over $2 billion in fines and penalties from HSBC, a London-based bank, for failing “to monitor” over $670 billion in wire transfers to and from Mexico between 2006 and 2010. And while the company “clawed back” bonuses given to its “most senior AML [Anti-Money Laundering] and compliance officers,” no one was prosecuted.

In sum, although US agents counted over $1 trillion in potentially laundered funds in that eight-year period, no one saw the inside of a jail cell.

This problem also arises when investigating precursor chemical flows. A former DEA investigator for Diversion Control, who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak, said that financial analysis was almost always done in a reactive way. And when it came to investigating Chinese companies that operate through the dark web or use cryptocurrencies — a mainstay of the precursor chemical and synthetic drug market writ large — US authorities had limited to no visibility.

“It’s like going into a dark wall,” the investigator said.

SEE ALSO: Corruption, Crypto Test LatAm Money Laundering Laws

In Mexico, the record is arguably worse. A 2018 evaluation by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an international inter-government watchdog, found that, while the government has a strong AML regime and a good understanding of the threats of money laundering, “it is nonetheless confronted with significant risk of money laundering,” stemming principally from organized crime-related activities.

Specifically, the FATF noted that the UIF — the intelligence agency responsible for identifying anomalies in earnings statements, financial transactions, company registries, and other means of obfuscating or camouflaging illicit — was not generating a sufficient “volume” of information for the Attorney General’s Office, the government body responsible for carrying out the judicial inquiries.

For its part, the Attorney General’s Office also came up short. According to the FATF, money laundering “is not investigated in a proactive and systematic fashion, but rather, on a reactive, case-by-case basis.”

The result is the above-mentioned dearth in investigations. Between 2013 and 2016, the FATF cataloged 339 cases. Of these, 103 resulted in the conviction of just 53 people.

“The figures call into question the effectiveness of investigations,” the FAFT wrote, perhaps understating Mexico’s glaring shortcoming in its efforts to follow the money.

Money Flows to China: The Prevalence of Cryptocurrencies

One positive the FATF noted in its 2018 report was the UIF’s cooperation with foreign governments in their investigations. At least one of these investigations, a US-led prosecution of a China-based clan, offers a glimpse of how multi-layered synthetic drug networks buy precursor chemicals from China.

In 2018, the US government filed a lengthy indictment against Fujing Zheng and his father, Guanghua Zheng, who are at the top of what it called the “Zheng drug trafficking organization” (DTO), outlining the network’s activities across the globe. The network advertised “custom synthesis” of chemicals and synthetic drugs, and the regular export of at least 36 synthetic drugs and precursor chemicals, including fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and other synthetic opioids.

While the indictment did not mention Mexico, Mexican newspaper El Heraldo, citing a leaked intelligence document, reported that the UIF had also investigated the Zheng network.

Through our own research, we found numerous connections between Zheng-owned companies and Mexico. Specifically — via an analysis of supply-chain data using Altana, a company that provides a dynamic map of global supply chains — we tracked one company listed on the indictment, Global United Holdings, that registered small shipments of textiles to two companies in Mexico and one in the United States.

Another, Shanghai Pharmaceutical Company, which the US indictment identified as the “legitimate face” of the DTO, shipped lab equipment and medical instruments to five different Mexico-based companies, research using Altana shows. This included a vial-pressing machine, a “powder-mixing machine,” pill presses, and chemical mixers.

Altana’s platform also registered small transactions from another company, Cambridge Chemicals, of bentonite, phosphorous acid, sodium laureth sulfate, and sugar — substances that can be used as essential chemicals or mixers in the production of fentanyl pills — to four Mexico-based companies.

The indictment briefly mentions the methods the network used to receive money. Initially, payments for the chemical substances and synthetic drugs were made via regular bank transfers, but increased surveillance from the Chinese government over its financial institutions allegedly forced the Zheng clan to switch to cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin.

In and of themselves, cryptocurrency transactions are not illegal, but some of what the Zheng DTO did could be illegal. For example, the indictment claimed it “misrepresented fund transfers and directed customers to misrepresent fund transfers”; it used “structured transactions,” so it would not trip the wires that require institutional and record-keeping safeguards; and it “bypassed Chinese restrictions and reporting requirements on fiat currency entering and leaving” China.

Our research corroborated some of these patterns, especially those related to the use of cryptocurrency to pay Chinese vendors. Several independent, Mexico-based fentanyl and methamphetamine producers told InSight Crime that chemical vendors in China seemed to prefer cryptocurrency for small-level transactions; the second option was bank transfers. And in our interactions with chemical purveyors on the Clearnet and dark web regarding fentanyl precursors, we found they leaned towards cryptocurrencies, specifically Bitcoin.

These methods were also evident in a recent series of indictments released in June 2023 by the US Justice Department. In one of the charging documents, prosecutors described a China-based chemical company receiving payments via “cryptocurrency” before sending fentanyl precursor chemicals to Mexico and the United States.

The June 2023 indictment does not specify which cryptocurrency was used or how the transactions were made, but investigators and prosecutors contacted by InSight Crime said the use of cryptocurrency by criminal networks is evolving. While the Zheng network used Bitcoin and did little to hide these transactions, according to one investigator who worked on that case, more recently criminal networks have trended towards the use of Tether and may be employing applications such as “blenders” or “mixers,” which mix transactions to muddy the crypto trail.

With a market cap of over $100 billion, Tether is one of the most-traded cryptocurrencies in the world and the most-traded “stablecoin” — i.e., pegged to the US dollar. It is appealing to traffickers for various reasons. In a report published in January, the United Nations noted that Tether had become “a preferred choice for crypto money launderers in East and Southeast Asia due to its stability and the ease, anonymity, and low fees of its transactions.”

The cryptocurrency is traded in such large amounts, it may also be servicing industrial-sized customers. In April, Reuters reported that Venezuela’s state oil company, PDVSA, was using Tether to sidestep US sanctions. And one investigator, who monitors large-scale illegal drug transactions in the millions of dollars, told InSight Crime that he had noted trading of large amounts of Tether.

The trading platform may also matter. The investigator cited above said the traffickers were using Tron, a decentralized blockchain-based operating system. It was founded in Singapore and has operational nodes across the globe, with its greatest concentration of nodes in China, according to Messari, a market-research firm. And the investigator said it is an attractive platform for criminal organizations because Tron is mostly based outside the United States and can help them avoid scrutiny by US investigators.

Another investigator we contacted who had examined the synthetic drug supply chain emanating from China noted that, in addition to Tron, traffickers were using Ethereum, a different blockchain-based operating system. The investigator surmised that this was because the criminal networks would “pay less of a fee” to China-affiliated exchanges such as Binance for these transactions.

At least one application on Ethereum has faced scrutiny. In August 2022, the US Treasury Department sanctioned Tornado Cash, a blender that was operating on the Ethereum platform. The blender, according to the Treasury Department, facilitated “anonymous transactions by obfuscating their origin, destination, and counterparties.” And in August 2023, the US Justice Department indicted Tornado Cash’s creator, claiming he had facilitated the laundering of up to $1 billion in criminal proceeds.

This was the second major effort to crackdown on blenders. But the proverbial game of whack-a-mole is difficult, in part because of the decentralized nature of the crypto business. For its part, Tether responded to the UN report, saying it was “disappointed” in the agency’s assessment and that its monitoring systems far surpassed those of traditional banks. It also said it had frozen $300 million in recent months, and in May, the company announced a partnership with the blockchain analysis firm, Chainalysis, to develop a “customized solution” for tracking illicit money flows.

Right Hand Not Talking to the Left

There are many reasons that Mexico has no cases related to financing precursor chemicals or laundering synthetic drug proceeds. It begins with poor data. There are no good estimates, for example, as to the size and scope of money laundering in Mexico. As the UIF itself points out in its National Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing Assessment 2023, “The Mexican State does not have an established methodology or guidelines that allow it to accurately measure the volume of illicit resources generated in the country because producing a document of this nature could contain unreliable variables.”

The UIF does provide statistics regarding criminal complaints — 166 in 2023 — and individuals and entities whose accounts have been included in the “blocked list” — 6,969 individuals or entities and 45,342 frozen accounts, totaling $4.45 billion pesos (around $262 million) in blocked funds as of February 2024. However, it is not possible to know how many of the criminal complaints have resulted in a prosecution nor, per its own admission, what the importance of the frozen funds is relative to the total illegal proceeds that are laundered in Mexico.

The government’s lack of transparency in these matters has been noted in public forums. The UIF’s opacity has spawned recurrent accusations of political bias, including in Mexico’s Congress. In the same vein, the Attorney General’s Office does not provide money laundering prosecution statistics and does not provide any context for the confiscation of proceeds from judiciary processes in which it is involved — other than asserting that the estimated total value in play for the most recent year it has statistics, 2022, was $1.5 billion pesos (or about $88 million), about a third of what the UIF has blocked.

But the core of the problem appears to be a conflict between these two key agencies and a discrepancy about how and whether to prosecute money laundering cases at all. While money laundering can be prosecuted on its own, most money laundering cases come with what is known as a “predicate offense.” In other words, there is an underlying criminal act — drug trafficking, human trafficking, corruption, etc. — which leads to the need to launder illicit proceeds.

In the case of Mexico, these prosecutions are subject to different investigative processes with widely differing objectives and institutional capabilities. While both Mexico’s Anti-Money Laundering Law (AML) and the federal penal code grant significant supervisory and investigative powers to the UIF, it is, in the end, an intelligence-gathering agency. The evidence it has is often raw and related to patterns of misbehavior, which it then passes to the Attorney General’s Office, the entity responsible for prosecuting the cases.

SEE ALSO: Mexico’s Laws to Regulate Chemicals Work on Paper But Not in Practice

For their part, the Attorney General’s Office has numerous special departments that can continue these investigations. The prosecutors, however, need proof that can withstand judicial scrutiny, which often requires more investigative legwork they are either: not prepared to do; do not have the time to do because of workload and inadequate staff; are paid by corrupt actors not to do; or do not think it is necessary to do since most of their cases already include predicate offenses that can lead to significant prison sentences.

The result is that few money laundering cases are even prosecuted, and none that we could find are connected to precursor chemicals or synthetic drug distribution and sales. In its 2018 report, the FATF noted solemnly that “financial intelligence does not often lead to launching ML (money laundering) investigations,” noting a significant difference in priorities between the UIF and prosecuting authorities.

“In view of the serious threat posed by the main predicate offenses, the competent authorities accord far more priority to the investigation of the predicate offenses and scant attention is paid to ML,” the FATF wrote.

The disconnect often plays out in public. In 2020, for example, current Attorney General Alejandro Gertz told Aristegui Noticias that the failure of the Attorney General’s Office in prosecuting cases was that the UIF failed to “provide all the proof.”

It was as if the attorney general thought the UIF was an adjunct prosecutorial unit.

Money Flows from Mexico

Another US investigation the UIF participated in was against the Zamudio Lerma network. In February 2023, the US Treasury Department sanctioned the network for its role as precursor suppliers of the Sinaloa Cartel.

The Treasury Department named several Zamudio Lerma family members and associates, as well as a series of companies that provided them with the requisite infrastructure to launder both the precursor chemicals and the proceeds of these sales. This included an import/export company, a pharmacy, a hardware company, and a real estate company. In addition, a Treasury Department sanctions list released in July 2023 named another family member who had been the director of Culiacán’s General Hospital and sanctioned an import/export company called REI Companía Interacional, which, using Altana, we investigated.

According to shipping records accessed via Altana, REI maintained relations with at least three Hong Kong and China-based chemical companies. One of these, Tai’an Herris Chemical Co., Ltd., sent 192 tons of n-methylformamide, a dual-use substance that is heavily regulated because of its use in the synthesis of methamphetamine. The records show that Tai’an Herris Chemical also sent 9.6 tons of methyl thioglycolate and 21.12 tons of isobutyronitrile to REI between April and October 2020. Another company, Shandong Tai’an Construction Engineering Group, sent at least nine shipments of a total of 128 tons of n-methylformamide, 40 tons of tartaric acid, and 19.2 tons of isobutyronitrile to REI between May and November 2020. All these substances can be used to produce methamphetamine.

Notwithstanding the participation of numerous law enforcement — the FBI, the DEA, and Mexican government agencies — as of publication, there were no known formal charges against any members of the network in the United States or Mexico.

However, the shipments appear to illustrate an important pattern as it relates to methamphetamine precursors and payments for them: Methamphetamine producers import less regulated pre-precursors and essential chemical substances, and, in these cases, there is little need to obfuscate the chemicals or the payment methods.

What’s more, payments for methamphetamine pre-precursors and essential chemicals can be hidden amidst large purchase orders that often include many other chemicals that do not have illicit uses.

In fact, using Altana, we found numerous companies in Mexico that follow a similar pattern. For example, one Monterrey-based company, which we do not name because it has not been sanctioned nor criminally charged, frequently deals with Chinese companies that sell controlled substances. And it reported importing 950 tons of methyl chloride in a dozen different shipments, as well as receiving a shipment of 26 tons of acetic acid. The first substance is an essential chemical for methamphetamine production and is not regulated in Mexico. The second is a pre-precursor for methamphetamine and fentanyl that is regulated in Mexico. Aside from these chemicals, the company imported hundreds of tons of other products, including cleaning products, industrial solvents, plastics, and soaps.

From what we can surmise, the payments for these chemicals were most likely done via bank transfers, reported to financial institutions, and did not raise any red flags given the wide swath of chemical transactions embedded in the purchase orders. In sum, when it comes to methamphetamine precursors, neither the shipments nor the payments are going to necessarily trip investigative wires.

SEE ALSO: Beyond China: How Other Countries Provide Precursor Chemicals to Mexico

But when it comes to fentanyl precursors, we found a different pattern. According to Altana data, beginning in 2020, REI received a series of random shipments that did not seem to correspond at all to their regular business practices.

In one of these, Cameron Sino Technology Limited, sent at least 40 shipments of what it listed as “lithium batteries” and “lithium battery chargers” to REI between August 2020 and March 2023, with the help of a Mexico City-based broker. Other companies listed motorcycle locks, paintings, pet toys, and security locks on the manifests of their shipments to REI.

Government investigators told InSight Crime that these types of random shipments raised red flags because of the possibility that they were mislabeling the items for the shipping manifests and bills of lading. The changes often followed changes in regulations in China. And whereas the stated amounts and weights of the shipped goods remained the same, the names of what was being shipped changed.

The pattern was particularly true as it relates to fentanyl precursors, and it is a common practice that authorities have identified in other cases, according to InSight Crime interviews with the Mexican navy and retired port officials, as well as per our clandestine interactions with chemical purveyors in China.

This is, in part, because the amount of precursors needed is much less than what is needed to produce methamphetamine. Thus, disguising the movement of the chemicals in small shipments of random products becomes a simple process.

Investigators also say the payments for fentanyl precursors are easily hidden amid a sea of random transactions. Aside from cryptocurrencies, as in the case of the Zheng network, the payments move via wire transfers and services like Western Union.

In some cases, criminal networks may also be trading goods for precursors. For example, José Alfredo Ortega, the minister for Public Security in Michoacán, told InSight Crime in December 2022 that brokers and buyers in the state were exchanging iron extracted from illegal mines on the state’s coast for precursor chemicals.

“We have identified that iron was sold irregularly to Chinese buyers and, in exchange, they brought in precursor chemicals,” Ortega said.

Two members of an armed group in the town of Aquila, which is located close to the mining region, corroborated this account.

Similarly, a 2022 Brookings Institution report concluded illegal trade in wildlife was being used by Mexican criminal groups as a means to buy precursor chemicals from China, and launder the money in the process. More recently, the Associated Press quoted a Mexican attorney who said that methamphetamine is exchanged in China for precursor chemicals.

Nonetheless, InSight Crime did not find any judicial cases in the United States or Mexico that document these types of payments. To be sure, the transactions, in particular for fentanyl precursors, are so small that they are difficult to track and may not be worth the effort. These micro-economic transactions are even more obscure in Mexico itself, where cash remains king.

Cash: Still King in Mexico

On a recent hot, sunny morning in Culiacán, Sinaloa, we traveled downtown to an area near one of the city’s main markets. There we saw dozens of young adults sitting beneath umbrellas on the street, just outside the dark-tinted windows of currency exchange houses. In all, we counted 30 on one street alone. As cars passed, they yelled, “Dollars! Do you want some dollars?”

Curious, we approached one to inquire about an exchange. The attendant did not request any form of identification or ask us to sign any documents, as is legally required. Had we proceeded with the transaction, we could have exchanged large sums of cash without any record of it in the banking system. And when we checked the government’s registry to see who of these had an active license to change currency, none of them appeared.

The street is a reflection of another reality that also makes money laundering and illicit financing difficult to fight in Mexico: the country’s reliance on cash. Cash dominates the financial landscape of Mexico, and its importance continues to grow, rather than decrease. According to Mexico’s Central Bank, as of February 2024, there were about 2.788 billion pesos (around $164 million) in bills and coins circulating in Mexico, a 9.9% increase from February 2023.

The increase outpaced inflation and also illustrated the continued importance of remittances, which a recent Reuters report said was also becoming a mainstay of money laundering operations of the Sinaloa Cartel. Remittances hit a record $63.1 billion pesos in 2023 ($3.7 billion), a 7.6% increase compared to the previous year, and an 89.5% increase compared to 2018, according to data from Mexico’s Central Bank.

Furthermore, according to the 2021 Financial Inclusion National Survey, 90.1% of Mexicans used cash for purchases under $500 pesos (or $30) and 78.7% for purchases over that amount, with similar trends observed across all regions of the country. Likewise, about half of the population did not have any savings in a bank account or debit cards.

The laws also favor cash and “analog” methods of payment that are not registered by the banking system. In Mexico, for example, it is possible to conduct large financial operations using cash or precious metals without running afoul of article 32 of the AML law. While there is a threshold for certain types of transactions, such as real estate, it is relatively high (see list below). What’s more, the list does not include transactions for chemicals, which, in effect, means there is no limit for the use of cash in making these purchases.

Even if one were to assume that there is a high level of compliance and enforcement for article 32 of the country’s AML law — which is unlikely, given the low number of prosecutions — it is clear that the prevalence of the use of cash and the relatively high legal thresholds for cash transactions might significantly reduce the necessity of integrating the money back into the system.

The implications of this cash flow in the precursor market are clear, especially when you consider the horizontal nature of the marketplace. There are, quite simply, numerous independent fentanyl and methamphetamine producers who import or buy chemicals on the local level.

These are relatively small transactions when measured in dollars. For example, four fentanyl producers told InSight Crime the investment to set up a production operation was close to a million pesos, or $58,000. Smaller labs could be set up with as little as $11,600, according to another independent producer.

Once a lab was running, the cost of buying the necessary chemical substances to produce one kilogram of fentanyl was also relatively low: The producers said it would run between $2,000 and $5,000, which could also be paid in cash in Mexico. The cost of 1-BOC-4-Piperidone, the preferred pre-precursor to manufacture fentanyl, for example, could vary between $1,000 to $4,000, according to our interviews with both local producers and our interactions with Chinese sellers — another transaction that could be satisfied via fiat once the chemicals were in Mexico.

The production of methamphetamine implies more costs, especially when setting up a lab, as the quantities are larger and more specialized equipment is required. According to methamphetamine producers interviewed in Michoacán, this can go as high as $157,000. The prices of the required pre-precursors and essential chemicals fluctuate constantly, according to our sources. But over the past year, the necessary substances to produce 120 kilograms of methamphetamine were worth between $23,000 and $35,000. As noted above, something close to these amounts could be paid via cash without tripping any investigative algorithms.

The small amounts that move via fiat also obviate the ability and desire of authorities to track and prosecute such crimes. Two former UIF officials who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity, said these transactions were simply too small.

“[These numbers] are not at all significant to raise any alarms in the financial system. It goes by unnoticed,” one of the officials said.

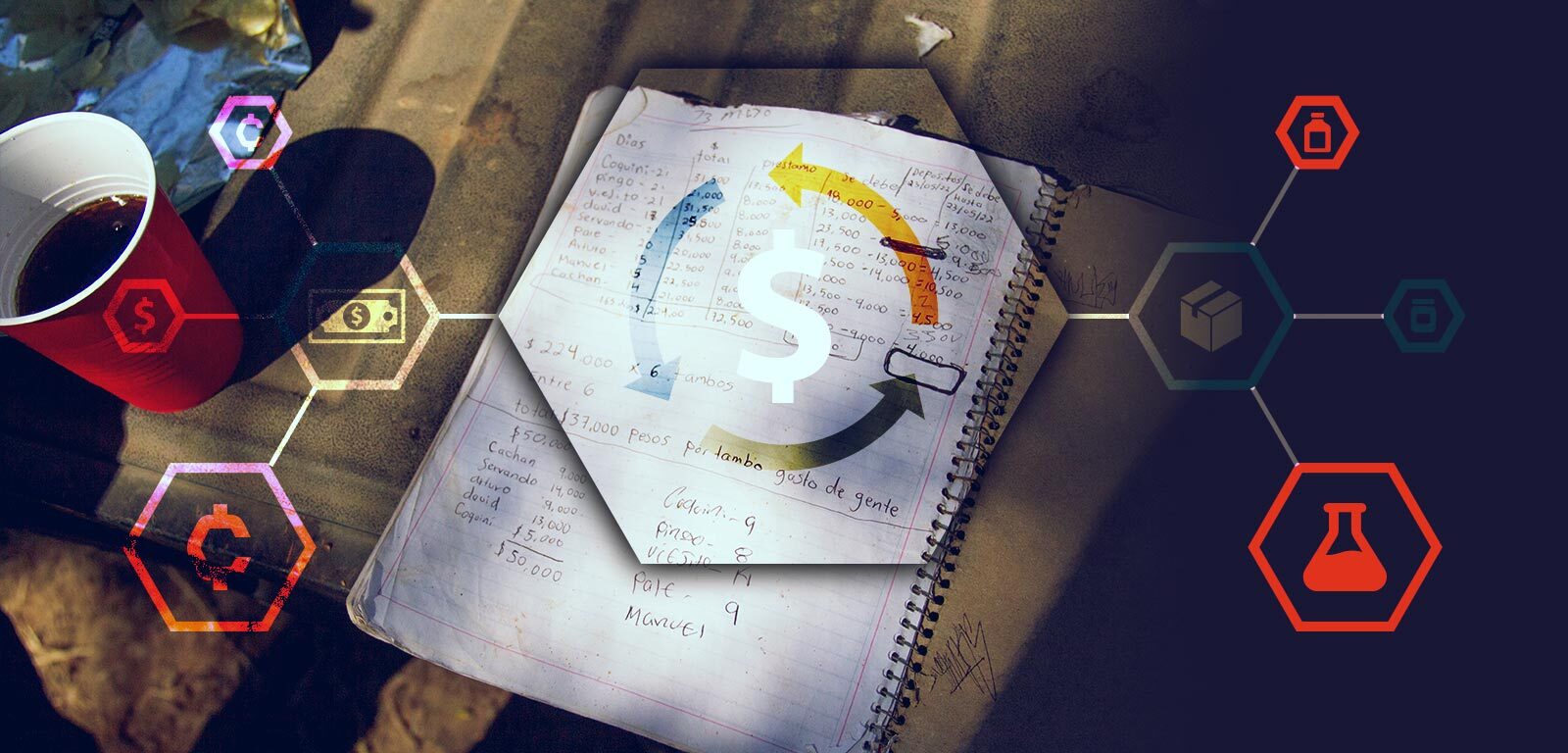

The UIF-Typology’s Real Life Twin

On August 27, 2019, Mexico’s Marines (SEMAR) seized over 23 tons of precursor chemicals in the Lázaro Cárdenas port of Michoacán, on the Pacific coast of Mexico. The chemicals arrived on a Dutch cargo ship at the request of Culiacán-based company, Distribuidora Agroindustrial Ocher.

In its account of the case, Proceso said SEMAR alerted the UIF, which began an investigation in the case. What it turned up looked remarkably similar to the case study — or the “typology,” as they had called it — cited at the onset of this report.

Like the case study, Ocher was a front company, which was connected to another Sinaloa-based company called Mi Pao, S.A. de C.V., which was also importing precursor chemicals. Both companies were receiving chemicals and machinery from a Hong Kong-based company, according to Altana.

And like the case study, the prime suspect had Asian ties. Proceso said the owner of Mi Pao was Tawainese national, Chiang Li Chun. As it was in the case study, Chun had been arrested in May. In Chun’s case, he was connected to a fentanyl laboratory where authorities found 40,000 counterfeit pills and 14 kilograms of powdered fentanyl.

A person with knowledge of the investigation told InSight Crime that the UIF eventually froze Ocher’s account. But no other public information is available about any prosecution of those implicated in the case.

*Jorge Lara, Jaime López-Aranda, Victoria Dittmar, and 穆小姐 contributed reporting to this article. Fact-checked by Peter Appleby.

Altana supports InSight Crime’s research into precursor chemical flows by providing access to the Atlas, a dynamic, AI-Powered map of global supply chains, as well as to its Counternarcotics Dashboard, an AI-driven model to flag narcotics trafficking risk within global shipment and business ownership data.