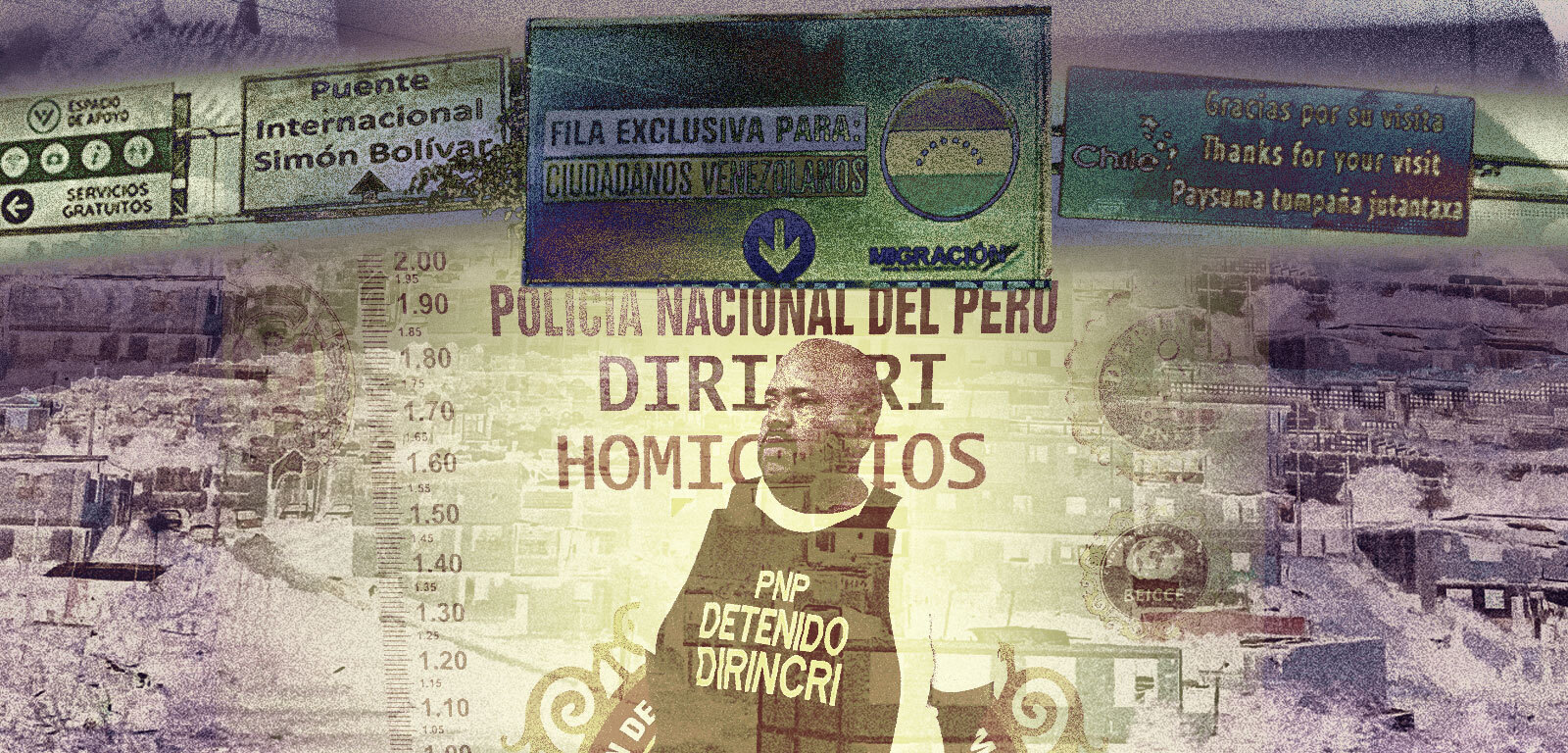

“Tour operators” offering trips to Bogotá, Medellín, and even as far afield as Ecuador and Peru, swarm anyone stepping off the Simón Bolívar International Bridge connecting Venezuela with Colombia. Street hustlers offer everything for the passing migrant, even ready with scissors to buy your hair in case you need a bit of extra money for the journey ahead.

For tens of thousands of migrants every year, this is their first step in fleeing Venezuela — and their journeys have become a big business. But everyone who wants a piece of that business, including the migrants themselves, must pay for the right.

*This article is the second in a three-part investigation, “Tren de Aragua: From Prison Gang to Transnational Criminal Enterprise,” analyzing how the Venezuelan mega-gang has become the fastest-growing criminal threat in South America by exploiting mass migration from Venezuela . Download the full report or read the full investigation here.

“These people arrived alongside the migratory flows, so they took advantage of the migrants,” explained a resident of La Parada, the first town many migrants pass through in Colombia, speaking in a strained voice, just quiet enough so the neighbors could not hear.

“These people” refers to the notorious Tren de Aragua, the Venezuelan gang whose rapid transnational expansion has raised alarm across South America.

For Tren de Aragua, taking control of La Parada was just the first step. In the five years since it first appeared here, the gang has built a far-reaching regional network, establishing a permanent presence in Colombia, Peru, and Chile, with further reports of their presence in Ecuador, Brazil, and Bolivia.

This rapid expansion came largely on the backs of the nearly 8 million desperate Venezuelans who have fled their country since 2015 looking for a better life. Whereas the world looked at this mass migration and saw a humanitarian crisis, Tren de Aragua saw a business opportunity, and it took full advantage.

Exploration: Following the Migration Flows

The first reports of Tren de Aragua’s expansion outside of Venezuela appeared in 2018. This coincided with the first peak of the Venezuelan migrant crisis, when over 1 million people were leaving the country each year. In this initial wave of mass migration, huge numbers of Venezuelans headed to Colombia, Peru, and Chile, and these same countries have become the epicenters of Tren de Aragua’s international expansion.

In each of these countries, Tren de Aragua’s expansion has followed a followed a three-step process. First comes the exploration of new territories. Then there is the penetration of the local underworld. And finally comes the consolidation of the cell’s local presence.

The exploration phase begins when the gang arrives in new areas that are either border crossings, hotspots along migration routes, or urban centers with large Venezuelan diasporas.

In Colombia, it began in and around La Parada, but soon spread to the Colombian capital, Bogotá, the city with the largest Venezuelan diaspora.

As Venezuelan migrants headed further south, so did Tren de Aragua. Soon the group had set up cells in several Peruvian cities with large diasporas: Lima, Arequipa, and Trujillo. Next came Chile, where the gang first moved into the northern border towns of Arica and Tarapacá, then later into the cities of Santiago and Concepción.

SEE ALSO: Venezuelan Migrants Remain Easy Prey for Organized Crime

“These are cities where there’s a lot of economic movement, where money flows, so that’s where they establish themselves. That’s what they call the plaza, where there’s money,” explained General Luis Jesús Flores Solís, the head of the Peruvian National Police’s Anti-Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling Directorate (Dirección Contra la Trata y Tráfico Ilícito de Migrantes de la Policía Nacional Peruana – PNP).

During the exploration phase, the gang’s arrival in these places was likely opportunistic rather than guided by a strategic masterplan. And the opportunity they were seeking to exploit came in the form of their fellow Venezuelans.

Controlling migration routes and Venezuelan migrant populations offered lucrative income sources in the form of migrant smuggling, human trafficking for sexual exploitation, and extorting or robbing diaspora communities and migrants in transit. The members of Tren de Aragua were predators swimming in a sea of migrants, looking for any opportunities to rob or exploit.

Moving among migrants also allowed Tren de Aragua to maintain a low profile, as while Venezuelans know and fear the group, migrants are less likely to report crimes out of fear of repercussions such as deportation, or a lack of trust in local authorities.

Penetration: Wielding Violence and Fear

Between 2020 and 2022, during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, migration rates began to slow, although demand for human smuggling services rose as borders slammed shut. Tren de Aragua cells that had already been established along migration routes moved from exploration into the penetration phase. They identified local criminal economies unrelated to migration that they could exploit, and they attacked any competition or potential rivals.

The gang’s capacity to move into this next phase was determined by local conditions. These included not only the presence of criminal economies with low barriers to entry, but also factors such as relatively low murder rates. This increased the impact when the gang used highly publicized acts of brutality and murder to terrorize both the population and potential competitors into submission.

One migrant in northern Chile, who spoke to InSight Crime anonymously for fear of reprisals, highlighted the fear that Tren de Aragua struck into the population.

“There are houses where they did horrible things. Torture and homicides. I’ve heard they buried or burned people alive,” she said.

Tren de Aragua capitalized on this fear to move into new criminal economies such as extorting local businesses and sex workers, loan sharking, and drug dealing. They published videos of brutal assassinations of sex workers who refused to pay extortion fees and threatened extortion victims with grenades in Peru. And they allegedly dumped dismembered bodies on street corners in Bogotá.

In some cases, they all but eradicated the competition.

“There are no more Peruvian pimps [in Lima]. Why? Because [Tren de Aragua] killed them,” General Flores told InSight Crime. “Nobody wants to mess with them due to their extreme violence.”

Consolidation: Setting Down Roots

As Tren de Aragua cells cemented control over local criminal economies, they also established their financial base and built criminal structures required to make their operations sustainable and resilient, entering the consolidation phase.

In this phase, the gang has sought to infiltrate the state through corruption networks; to build increasingly sophisticated money laundering operations; and to form alliances with, recruit, or assimilate other criminal actors operating in the area.

The group’s consolidation has been most evident in Peru and Chile, where it has set up transnational financial operations.

Chilean police have identified cells laundering money by purchasing motorcycles and other vehicles, which they then rent out to migrants and informal food delivery workers. The cells then transfer some of this laundered money back to Venezuela via Bitcoin and Western Union payments, among other modalities.

Multiple Peruvian security forces and government officials also reported to InSight Crime that some of the laundered money earned in Peru is sent back to the leadership in Venezuela. Security officials, most of whom asked to speak to InSight Crime anonymously, reported finding examples of cells using Western Union transfers, shell companies, and by forcing the family members of the gang’s victims in Venezuela to receive payments in their bank accounts.

“They have different methods, and they’re constantly improving their modus operandi to send money to Venezuela,” General Flores said.

There are indications that the gang may have entered the consolidation phase in Colombian cities as well, primarily through corrupting police officials.

As early as October 2022, there were reports of police working with Tren de Aragua in Bogotá’s Kennedy neighborhood. Months later in early 2023, officials arrested several police officers allegedly working with the gang in Villa del Rosario, the municipality where La Parada is located in the border department of Norte de Santander.

Residents of La Parada, who spoke to InSight Crime on the condition of anonymity, said they could not be sure whether the police stationed in the area were corrupt or whether they were just outgunned by Tren de Aragua.

“I believe that the police know [what Tren de Aragua is doing]. The police are on their side,” said one of the residents, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons.

Another, though, pointed to a short concrete wall surrounding the front porch of his house, remembering a time that alleged members of Tren de Aragua were involved in a shootout in the neighborhood.

“There were two officers on a motorcycle patrol, they hid right here,” he said. “What were they going to do? There were six people with a rifle, and they were just two police with a pistol.”

A Stalled Expansion

Although Tren de Aragua has successfully moved through the three phases in Peru, Chile, and Colombia, its efforts to expand in some regions have been limited or even repelled completely by criminal competition.

Tren de Aragua’s expansion in the region around La Parada spurred violent clashes with the guerrillas of the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN). While for now these clashes seem to have died down, it is clear the gang is not capable of militarily challenging the heavily armed, well-trained, and experienced ELN, limiting its expansion options in a region dominated by the rebels.

In Bogotá too, Tren de Aragua has confronted entrenched local gangs, and while it has managed to carve out a space for itself, opposition and competition from local gangs has curbed its potential for growth.

SEE ALSO: Gaitanistas and Tren de Aragua Unlikely to War Over Bogotá, Colombia

Perhaps its biggest failure, however, came in Peru, and the port city of El Callao, which has long been violently disputed by gangs due to its role as a transnational cocaine shipment point.

There, the gang tried and failed to force its way in, according to a source in the PNP’s Special Investigative Brigade Against Foreign Crime (Brigada Especial de Investigación Contra la Criminalidad Extranjera), who requested anonymity because he was not authorized to speak on the record.

Tren de Aragua “have entered El Callao, but they were forced out, because let me tell you, [the gangs in El Callao] are on the same level. They’re hot-blooded,” he said.

Tren de Aragua’s Cover Has Been Blown

Criminal rivals are not the only enemies pushing back against Tren de Aragua’s transnational expansion. The gang is also increasingly facing off against local security forces.

In the initial stages of its expansion, Tren de Aragua was frequently able to pass through the exploration phase and into the penetration phase before local authorities were even aware of its presence. However, its heavily publicized use of violence has since made it a high-priority target for governments across the region.

The first operations targeting Tren de Aragua in Colombia took place in La Parada with the arrest of eight alleged gang members in July 2019. In the following years, authorities arrested at least 23 more alleged members in the area, according to InSight Crime’s media monitoring.

But the gang was not seen as a serious threat worthy of large-scale security operations until 2022, when authorities in Bogotá arrested at least 30 alleged gang members over the course of the year.

In Peru and Chile, the gang has been targeted with greater force and consistency. Peruvian authorities even carried out “mega-operations” in November and December 2022, arresting 30 Tren de Aragua members in Lima and 23 members in Arequipa.

Chilean authorities similarly carried out several operations targeting the gang in 2022, with up to 40 alleged members brought before the court in Arica and several more arrests in Tarapacá. The arrests continued with dozens of alleged members and leaders detained in the first half of 2023 in Santiago, Tarapacá, and Concepción.

Despite the sustained operations targeting Tren de Aragua outside of Venezuela, the gang’s cells have proven resilient, and for now their operations continue in the regions where they have consolidated.

“With these people, you cut off one arm and two more grow,” said a source from the Peruvian Attorney General’s Office, who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity.

Reports of new cells also continue to surface, with news stories and official investigations flagging potential cells in the cities of Chimbote and Piura in Peru, and Barranquilla, Ipiales, Cali, and Bucaramanga in Colombia.

However, authorities suspect some of these may be copycat groups seeking to capitalize on Tren de Aragua’s growing infamy. Even if these are genuine cells, there is little to suggest they have successfully moved beyond the exploration phase, and the dizzying pace of the group’s initial expansion appears to have slowed.

Not only is Tren de Aragua now being confronted both by criminal rivals and the security forces, but at the same time the conditions that permitted its expansion are changing. Venezuelan migration in South America has fallen, with many Venezuelans now instead heading north towards the United States. High levels of competition from powerful organized crime groups along these routes that already profit from well-established migration flows will likely limit their chance to replicate their South American successes along the road northwards.

Back home in Venezuela, meanwhile, Tren de Aragua’s stronghold and headquarters of Tocorón prison has been raided and ostensibly taken over by the Venezuelan government. The ground has shifted beneath Tren de Aragua’s feet, and now it remains to be seen whether it can establish another safe haven to run and plan operations, allowing its transnational criminal empire to continue to expand, or whether it will be forced into retrenchment and decline.