As the Colombian government negotiates peace with some of the country’s largest armed actors, protecting the rights of children targeted and recruited by these groups poses a significant challenge.

Colombia has experienced 16,900 cases of child recruitment since 1962, according to the Memory and Conflict Observatory (Observatorio de Memoria y Conflicto), a research center dedicated to documenting violence and victims of the armed conflict in Colombia. Children between 12 and 17 years old made up the majority, with 12,950 cases. Of these, 49.7% were students and 26.6% were girls.

SEE ALSO: Colombian Armed Groups Continue Recruiting Children Amid Peace Talks

Armed groups are the main drivers of child recruitment in Colombia. The guerrillas, including the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN) and the now-demobilized Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), are the main alleged perpetrators of this crime. These groups are responsible for 57% of the cases, with Antioquia (15.5%), Meta (9%), and Caquetá (7.5%) the most affected departments.

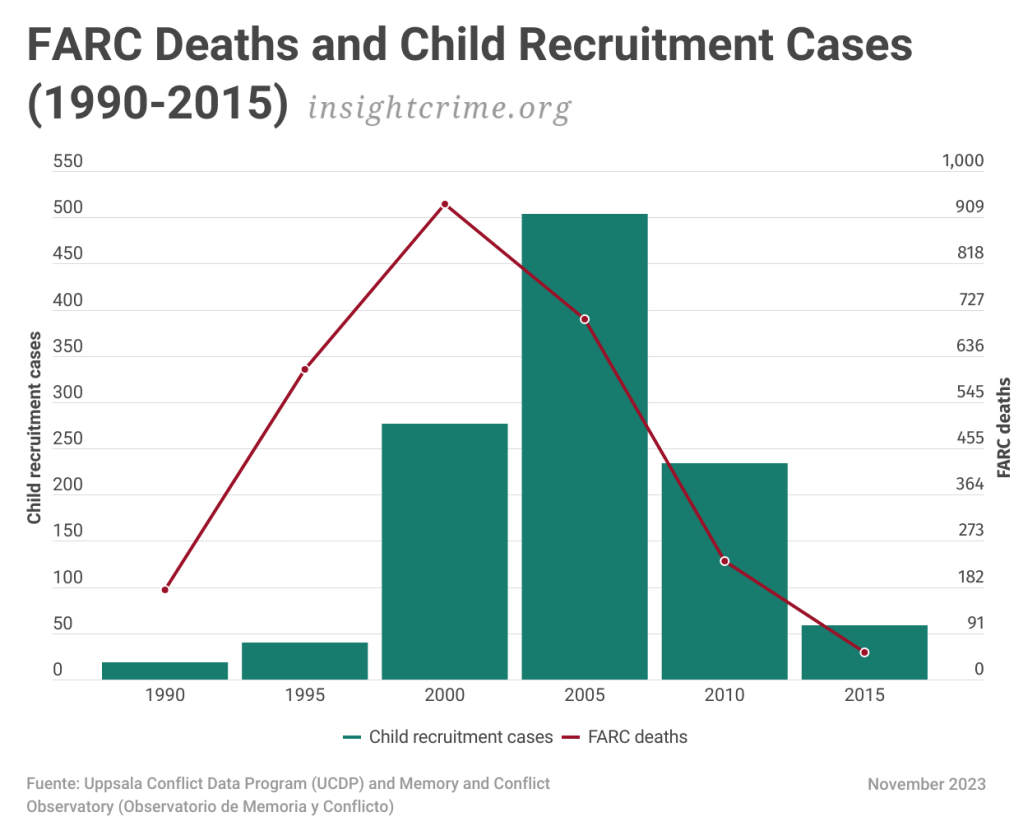

Child recruitment peaked in the early 2000s, and the observatory reports a 98% reduction in cases between 2003 and September 2023. But criminal groups still use recruitment to boost their ranks.

“The observatory’s figures suggest there is a reduction in cases of child recruitment, but this decrease is due to under-reporting caused largely by the fear of reporting in territories governed by criminal structures,” a sociologist and analyst of Colombia’s armed conflict told InSight Crime on condition of anonymity.

The ELN stands accused of at least 24 cases of child recruitment between 2021 and 2023, according to Colombian authorities. Additionally, a member of the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia – AGC) recently admitted to “having instrumentalized adolescents to carry out criminal actions in Antioquia,” according to the Colombian Attorney General’s Office.

Below are three conclusions about factors driving criminal groups to recruit minors in Colombia.

More Criminal Activity Leads to More Recruitment

Non-state armed groups and/or rebels that finance themselves through illegal activities are more likely to recruit children to strengthen their ranks. These illicit pursuits can supplant their political goals, making them more likely to engage in abusive behavior towards communities, academic studies suggest.

In the past, paramilitary groups were primarily focused on a politically-motivated fight against the leftist guerrillas. It was only in 1986, when they entered the drug trade that the first cases of child recruitment by these groups were registered.

Recently, the Central General Staff (Estado Mayor Central – EMC) of the ex-FARC mafia — a dissident faction that walked away from the peace deal between the FARC and the government in 2016 — led by Néstor Gregorio Vera, alias “Iván Mordisco,” has also turned to child recruitment.

The group has used minors to swell its ranks and consolidate control over important drug trafficking corridors in the west and south of the country. In November, authorities recovered two minors who had allegedly been recruited by the faction led by Mordisco in Huila. The army identified them as they guarded a van carrying drugs bound for the departments of Caquetá and Cauca, reported Caracol.

There are also reported cases of the ELN continuing to recruit minors and participate in illicit economies amid peace negotiations with the Colombian government. In November, the governor of Antioquia, Aníbal Gaviria, reported that the guerrillas tried to recruit 12 minors in that department.

A ‘Solution’ for Desperate Groups

Armed groups under pressure from rivals and security forces may see recruiting children as a quick fix to their problems.

The FARC’s highest peak of child recruitment — 286 cases — was in 2003, following four years of war with right-wing paramilitaries and just after the government launched one of its most comprehensive military strategies to weaken the guerrillas, Plan Patriota.

In Putumayo, one of the departments with the largest military deployment under Plan Patriota, there was a 283% increase in cases of child recruitment between 2002 and 2003.

The current administration has taken a different tact, foregoing military operations for peace negotiations. But President Gustavo Petro’s “Total Peace” policy has still propelled armed groups to reinforce their ranks by recruiting minors. Both the ELN and the EMC, who have been in conversation with the government since 2022, have employed this strategy as a backup in case negotiations fail or some of their members desert the process.

Past peace talks have prompted the same response. The ex-FARC mafia, for example, recruited children to boost their numbers after many of their former comrades decided to disarm under the 2016 peace treaty with the Colombian government. Two years later, the group had recruited 82 children, the most of any armed group in the country.

In 2019, as criminal groups clashed over the FARC’s former territories and illegal economies, the Attorney General’s Office warned of increased recruitment of minors by the ELN and the AGC in eight Colombian departments. “These recruitments are the product of territorial disputes between the aforementioned armed actors, fighting for control of trafficking routes, illicit crop regions, and illegal mining sites,” the agency reported.

Numerical Advantage in Territorial Disputes

Child recruitment can bolster the ranks of groups looking for an advantage in territorial disputes.

When the FARC signed a peace agreement with the Colombian government in 2016, it prompted a drastic reconfiguration of Colombia’s criminal landscape. Existing armed groups began to fight over the criminal rents the FARC had abandoned, and one of their strategies to increase their power was child recruitment. A recent UNICEF report showed that the ELN consolidated its position as the main recruiter of minors, followed by FARC dissidents and the AGC.

SEE ALSO: 3 Takeaways From UNICEF Report on Child Recruitment in Colombia

Although the observatory’s figures register only 12 victims of child recruitment between January and September 2023, the nonprofit Coalition Against the Recruitment of Children in Colombia’s Armed Conflict (Coalición contra la vinculación de niños, niñas y jóvenes al conflicto armado en Colombia – COALICO) reported at least 48 cases that occurred during the first half of the year.

President Gustavo Petro’s Total Peace policy may be prompting new clashes over territory. As the playing field continues to shift, criminal groups will try and prepare for any eventuality.

“We will only see this war continuing to intensify,” said the sociologist and analyst of the Colombian conflict. “The armed actors will try and strengthen themselves in the midst of the transformations generated by the government’s peace project, and one of their tactics will be to expand their ranks by recruiting minors.”