On September 21, 2021, Javier Algredo Vázquez was on his way to a US law enforcement office to reclaim chemical substances authorities had seized from him days earlier. In some respects, his trip that day was a remarkable act of hubris. But in other respects, it could be seen as business as usual.

The 50-year-old was born in Mexico and had lived with his family for decades in Queens County, New York, where he had worked at a prestigious hotel chain for over 15 years. But Algredo was also an entrepreneur. In the decade prior, he’d created a company that did regular business with chemical distributors in various countries. His brother, Carlos, was also a businessman with a seemingly prominent chemical import company in Mexico.

Their businesses, however, were under scrutiny. Unbeknownst to both at the time, Carlos had been indicted by US justice officials for charges related to precursor chemical distribution and methamphetamine production and trafficking. More importantly, his clandestine business partners in Mexico had already been designated in the United States as one of the main purveyors of fentanyl, the deadly synthetic opioid that was responsible for tens of thousands of overdose deaths in the country each year.

In spite of the network’s nefarious ties, the brothers could also claim to be following international standards and global regulatory conventions. Although some of the chemicals they sold were heavily regulated in the United States, Mexico, and China, they were not in India, Germany, and Turkey. What’s more, Javier had legitimate paperwork to back up his commercial transactions.

In this context, it’s not clear if Javier ever expected to be in the crosshairs of the authorities. But as soon as he arrived at the office, he was arrested and accused of providing chemical substances from various countries to criminal groups in Mexico for the production of synthetic drugs. Among his clients, prosecutors said, was the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG), one of the world’s most powerful drug trafficking organizations and one of two major suppliers of fentanyl to the United States.

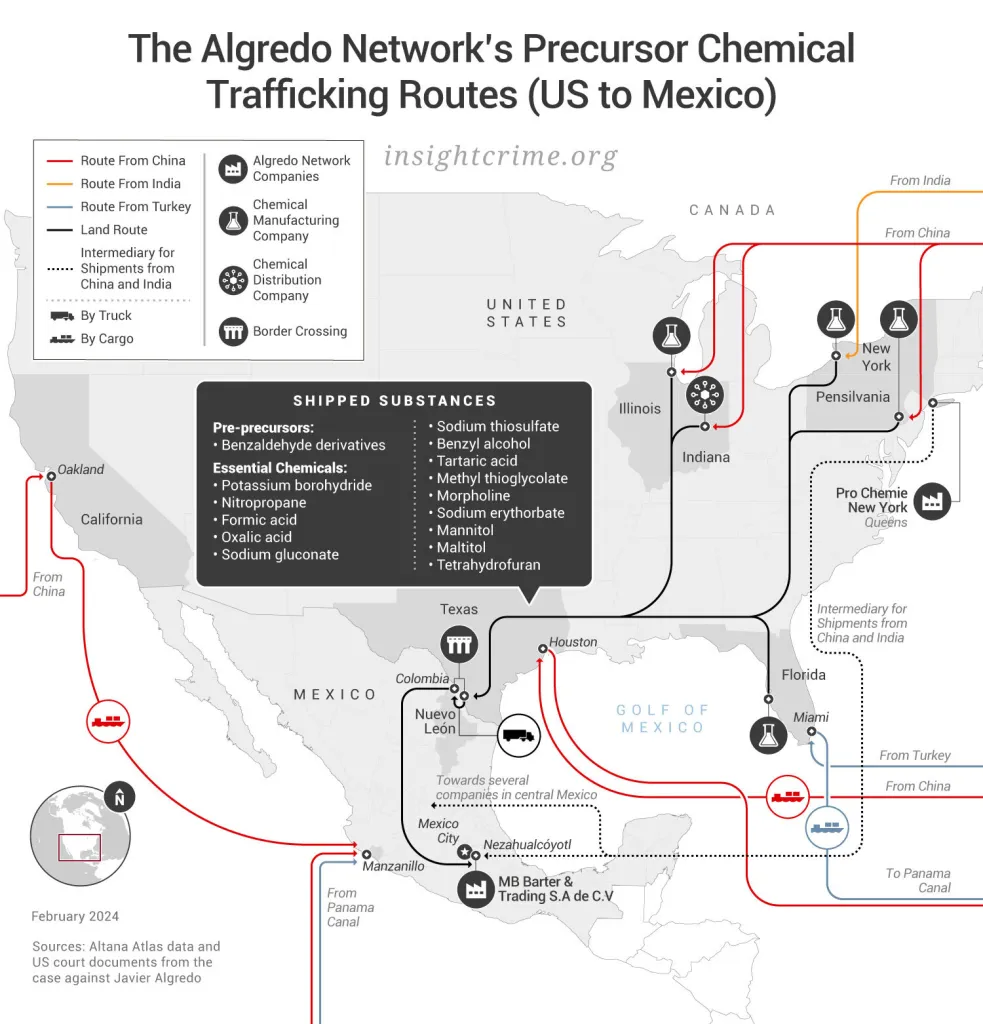

Using various front companies, prosecutors alleged that the Algredo brothers made regular chemical purchases, primarily from Chinese chemical suppliers, that were later used to produce synthetic drugs. China is one of the world’s largest chemical production hubs and the primary source of precursor chemicals used in fentanyl and methamphetamine production in Mexico, as InSight Crime has previously reported.

However, the Algredo brothers’ operation extended well beyond China. US prosecutors claimed the brothers had also established a vast network of chemical suppliers in India and Turkey. And an InSight Crime analysis of shipping data revealed numerous other transactions with companies in Germany and the United States. The chemicals the brothers purchased left major seaports in shipping containers that crossed both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

The Algredo brothers’ diverse supply chain is typical for these underworld markets. While China remains a key hub, brokers who supply synthetic drug producers in Mexico rely on chemical industries in several countries across Europe, Asia, and the Americas, according to dozens of interviews InSight Crime conducted over two years with synthetic drug producers in the Mexican states of Sinaloa and Michoacán, law enforcement agents and government officials from various countries, and academics and representatives of multilateral organizations.

SEE ALSO: Brokers: Lynchpins of the Precursor Chemical Flow to Mexico

The availability of these chemicals globally is one of the principal challenges law enforcement faces in curbing the synthetic drug trade. While China has cracked down on the production and sale of certain chemicals over the last decade, regulations and laws of other chemical-producing countries are often far less strict, and have numerous loopholes and gaps in enforcement. In fact, many of the substances needed to produce synthetic drugs are legally produced and marketed for numerous industries, making it easier to divert them for illicit purposes without being detected by authorities and the chemical companies that are supposed to be monitoring their own supply chains.

The result is a seemingly endless supply of the raw ingredients needed to make the deadliest drugs the world has ever seen.

Different Countries, Different Laws

In Javier’s indictment and in other court documents related to the case, prosecutors in the District of Columbia said he had used Pro Chemie New York Inc., a company he owned and had registered in the state of New York, to acquire these chemical products. His brother, Carlos, allegedly received the shipments in Mexico through another company, MB Barter & Trading S.A. de C.V., which was based in Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl in the State of Mexico.

Between 2018 and 2021, the Algredo brothers’ network diverted a total of 1,453 tons of chemical substances for methamphetamine production, 1,848 tons of substances used to enhance the potency of methamphetamine, and 44.1 tons of chemicals for fentanyl production, according to court records. Most of these chemicals came from China.

Nonetheless, the Algredo brothers also dealt with companies in other countries. For example, they obtained acetic acid from Turkey and sodium carbonate from Germany, according to the Altana Atlas, a dynamic map of global supply chains. These substances, which are used in the production of fentanyl and methamphetamine, are strictly regulated in Mexico. But in Turkey and Germany, they are not.

The patterns point to the central weakness of the current global regulatory system. Synthetic drug producers rely on a variety of substances, from precursors that are highly regulated, to essential chemical substances with dual uses. As regulators and law enforcement place controls on precursor chemicals, synthetic drug producers adapt their formulas so that they can use “pre-precursors,” and shift their supply lines in the process.

Although most countries are party to international conventions that provide guidelines for controlling and monitoring the use of these chemicals, regulations and laws vary widely from country to country. These disparities have significant implications.

To begin with, the lack of global agreement on the control of chemicals gives drug producers a wide variety of potential suppliers and transit points. When regulations increase in one country, as they have in Mexico and China, criminal networks find new substances and suppliers in countries with fewer controls.

Expanding the geographic scope of potential suppliers, as well as trafficking routes, also helps traffickers elude detection, several methamphetamine and fentanyl producers told InSight Crime. They use companies and transporters that offer quality products while minimizing risk in transit, they explained.

“We look for the most convenient route, which is not necessarily the most direct. … Wherever it’s possible,” said one coordinator of several clandestine synthetic drug laboratories in Culiacán, Sinaloa.

The result is that India, Germany, the United States, and Guatemala are now among a growing list of countries that play an important role in the supply chain of chemical substances used to produce methamphetamine and fentanyl in Mexico. Aside from China, these were the countries that were most frequently cited in judicial records consulted by InSight Crime, data of chemical shipments documented in the Altana Atlas, interviews we conducted with officials in these countries, and our fieldwork across Mexico’s synthetic drug-production epicenters.

While India serves as a country of origin due to its significant chemical industry and lenient regulations, Germany and the United States serve as both source countries and transit points for pre-precursors and essential chemicals. Meanwhile, Guatemala acts as a key transit point for chemical substances that are diverted before being transported to Mexico.

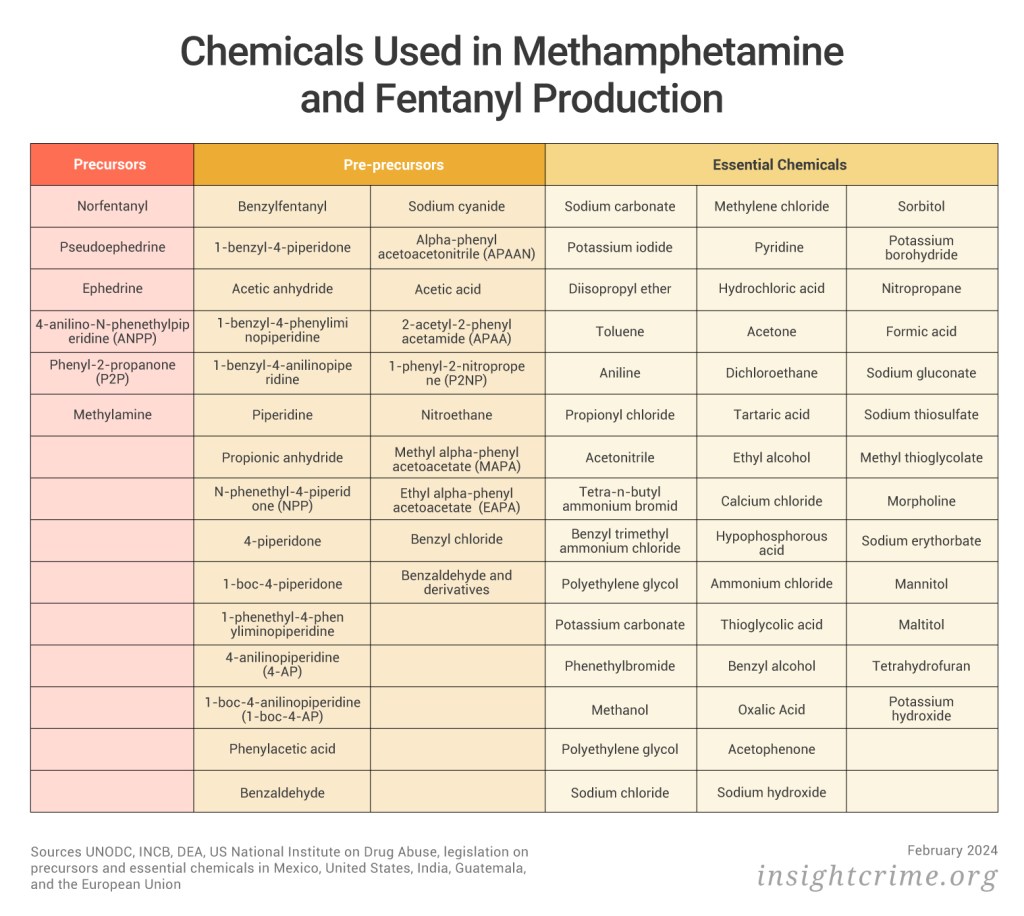

Using a list developed by the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) and various government counternarcotics and regulatory agencies’ lists, as well as open-source methods of synthetic drug production, InSight Crime identified 30 key precursors and pre-precursors, and another 43 key essential chemical substances that are currently used in the production of fentanyl and methamphetamine.

Of our bespoke list, Mexico has put 23 of these precursors and pre-precursors, along with 18 essential chemical substances on its controlled-substances list; the United States has 22 precursors and pre-precursors, along with 4 essential chemicals on its controlled-substances lists; Guatemala has 19 precursors and pre-precursors, and 12 essential chemicals on its watch list; Germany has 17 precursors and pre-precursors and 3 essential chemicals on its watch list; and India has 13 precursors and pre-precursors and none of the essential chemicals on its watch list.

The lack of uniformity even applies to the most important chemicals for synthetic drug production. For example, methylamine is used in the chemical, agrochemical, and pharmaceutical industries, but it is also an oft-used precursor for the production of methamphetamine and was one of the chemicals the Algredo brothers were trafficking to the CJNG in large quantities. It is included in Mexico’s federal law on precursors and is on the US list of controlled chemical substances. However, it is not considered in any regulations in India, and it is only monitored on a voluntary basis in Germany. Similarly, benzylfentanyl, a fentanyl pre-precursor, is on watch lists in Mexico and the United States but is not strictly regulated in India, Germany, or Guatemala.

These disparities mean that a large part of the precursor chemical supply chain can be sourced legally. For example, the Algredo network’s shipments to Pro Chemie New York and MB Barter & Trading may have met regulations. They made purchases from chemical companies in India, Germany, and the United States, some of which have operated for decades and supplied chemical substances to several billion-dollar industries. This was what may have given Javier Algredo the confidence to try and reclaim his lost merchandise that fateful September 2021 day.

His suppliers were also not necessarily transporting controlled substances. And they could have formed part of the precursor distribution chain without being aware that the chemical products they were selling were being diverted to produce illegal synthetic drugs in Mexico. What’s more, while regulations on the companies producing and trading chemical products may be comprehensive, they may not require the companies to do much due diligence in terms of collecting comprehensive data on the end-users acquiring these substances.

In terms of a lack of due diligence, the Algredo network is a case in point. Neither the company addresses for Pro Chemie New York and MB Barter & Trading registered with US and Mexican authorities, nor where they reportedly received the multi-ton chemical shipments, reflected a company that handled these types of products. In fact, a Google Maps search of both locations revealed they were homes located in residential areas. There was also no evidence to suggest they had the infrastructure in place or that other chemical distribution companies were operating in the area. (See below)

India: Large Production, Few Controls

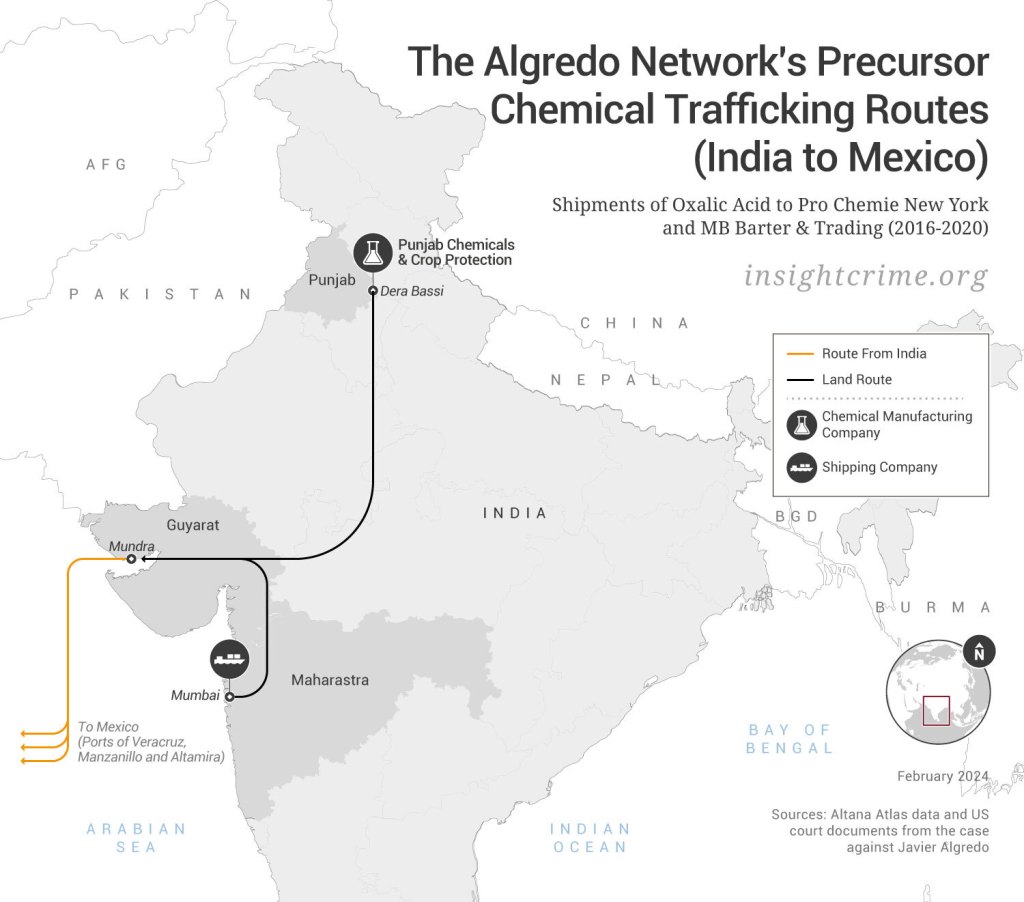

On December 19, 2020, a ship departed the port of Mundra in northwest India and entered the Arabian Sea loaded with 22.6 tons of oxalic acid. The chemical is mostly used as a cleaning product, but it is also an essential chemical used to synthesize methamphetamine. The cargo’s final destination was the Port of Veracruz, on Mexico’s Gulf Coast. Just six months later, two more shipments containing several tons of oxalic acid departed from Mundra en route to the Mexican ports of Veracruz and Manzanillo, on the Pacific coast.

While Pro Chemie New York purchased the chemicals, it was MB Barter & Trading that was listed as the “notify party” on the bill of lading. The supplier was Punjab Chemicals & Crop Protection, a chemical producer with decades of experience distributing over 220 products from its base in Dera Bassi, Punjab, in northern India.

US court documents in the Algredo case mention Punjab Chemicals, but they do not say whether the company was aware that the chemicals would be diverted for illicit drug production in Mexico. InSight Crime contacted representatives of the company but did not receive a response by the time of this report’s publication.

However, with the assistance of Altana, InSight Crime found other suspicious transactions by the company. Between 2016 and 2020, Punjab Chemicals conducted six other transactions with Pro Chemie New York, shipping a total of 154 tons of oxalic acid to the ports of Veracruz and Manzanillo, according to shipping data. During that same time, it also sent 40 shipments of oxalic acid to three other chemical companies in Mexico. Two of the companies they traded with are frequent buyers of chemicals on the US government’s lists of controlled substances, according to Altana.

The Altana Atlas also showed that between 2017 and 2020, at least one other company based in Mumbai, India, sent nearly 177 tons of oxalic acid in eight shipments to MB Barter & Trading. These were all sent from the port of Mundra to the ports of Altamira, Veracruz, and Manzanillo in Mexico.

All these shipments are small compared to the total amount of oxalic acid imported by Mexico in any given year, but they are still significant. For instance, in 2020, the total amount of oxalic acid imported by Mexico was at least 2,324 tons, according to the Altana Atlas. The December 2020 shipment from Punjab Chemicals that departed from the port of Mundra would therefore account for 1% of that yearly amount.

Oxalic acid is not on any watch lists in India, Mexico, or the United States, so the transactions documented in the case against Javier Algredo were legal, and neither the Punjab-based company nor anyone from the company have faced charges. But it is this combination of lax regulations and a vibrant chemical industry that makes India increasingly important in the flow of precursor chemicals to Mexico.

Globally, India ranks as the seventh-largest producer of chemical substances and the third-largest in Asia. The chemical industry accounts for 7% of its gross domestic product (GDP). Additionally, India’s pharmaceutical industry supplies 50% of the global demand for vaccines, 40% of generic drugs consumed in the United States, and 25% of all medicines required in the United Kingdom.

Some of these chemicals are potent. In 2022, for example, data collected by the INCB showed that India emerged as the leading exporter of N-phenethyl-4-piperidone (NPP), a pre-precursor used to produce medical-grade fentanyl, which is heavily regulated in India. The country is also an important source of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, two pharmaceuticals that are commonly used as precursors for methamphetamine synthesis in various parts of the world — although not in Mexico — according to the INCB’s 2022 annual report.

Trade between India and Mexico is also significant. In 2021, India exported products worth $4.44 billion to Mexico, $603 million of which corresponded to the chemical industry. Moreover, in 2023, India was the third-most common country of origin, after China and the United States, for shipments of pre-precursors and essential chemical substances to Mexico, according to the Altana Atlas. This included over 370 tons of acetic acid derivatives, 34 tons of benzyl alcohol, over 330 tons of acetone, and 8.1 tons of benzaldehyde derivatives, none of which are heavily regulated in India.

To some extent, the data tracks with previous reports by organizations like the Brookings Institution and the Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, as well as European drug-market analysts interviewed by InSight Crime. They have argued that India developed a greater role in the flow of precursor chemicals to Mexico after China imposed stricter controls over fentanyl, its analogues, and methamphetamine and fentanyl precursors over the last decade.

However, rather than coinciding with changes in regulatory regimes and laws in other countries like China, the data suggests that India has long been an important source for these types of products for Mexican buyers. While the total value of chemical exports from India to Mexico did grow from $470 million in 2019 to $600 million in 2021, there has not been any significant increase in the shipments of substances that InSight Crime identified as potentially being used for drug production since 2016, according to the Altana Atlas.

The companies that send precursors, pre-precursors, and essential chemicals to Mexico tend to be large firms with decades of experience in both domestic and international markets. They typically engage in the production, distribution, and export of pharmaceutical and chemical products, some of which are marketed for the food industry, veterinary care, and petrochemicals. Most of these companies are located near major cities, such as Mumbai, Hyderabad, Vadodara, Ahmedabad, and Mohali.

The Indian government has various requirements for chemical companies to export chemicals. In addition to issuing a permit, they request that exporters fill out a form with their personal information and that of the importer, as well as details of the chemical substances, their intended use, and the company’s form of payment.

However, Indian regulations on precursors, pre-precursors, and essential chemical substances are less stringent than in other countries. Some precursors and pre-precursors for methamphetamine production, such as toluene, methylamine, nitroethane, and hydrochloric acid, which are heavily regulated in China, the United States, and Mexico, are not subject to any special regulatory controls in India. Fentanyl pre-precursors like piperidine are also not subject to any strict regulations.

This means that companies in the country are not obligated to report trade data of these less regulated substances to authorities. In turn, this impacts the notification process to the INCB or to any government who does have these chemicals on their lists of controlled chemicals. This creates a loophole, which provides an opportunity for diversion.

What’s more, the capacity of Indian companies and authorities to identify diversion strategies, such as the use of shell companies, is limited. In its 2021 report, the INCB noted that chemical and pharmaceutical companies in India were at risk of diverting substances to the illegal market and recommended the country strengthen its internal surveillance and voluntary cooperation with companies to address precursor chemical trafficking.

“The chemical industry in India is large and very poorly regulated,” Vanda Felbab-Brown, researcher and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told InSight Crime. She added that authorities have limited capacity to monitor and supervise the chemical industry, which has also become an important interest group in the country’s political arena.

Judicial cases have also shown how these gaps can facilitate the flow of chemical substances used for synthetic drug production in Mexico. In December 2018, for example, three Indian citizens were arrested in possession of 100 kilograms of NPP. This shipment was falsely marketed as flour and intended to be sent by air to Mexico. One of those arrested, Salim Dola, was later accused of working with an alleged Indian drug trafficker known as Dawood Ibrahim.

At the end of September 2018, three other people were captured in a fentanyl laboratory, including Manu Gupta, an Indian businessman. He allegedly used his company, Mondiale Mercantile, to establish commercial relationships with companies in Mexico to ship fentanyl precursors, according to a report by Forbidden Stories. Gupta is currently serving a 20-year prison sentence, according to Indian judicial documents.

The type of chemicals Gupta’s company shipped were not made public. But according to the Altana Atlas, Mondiale Mercantile made at least one shipment to Mexico of thioglycolic acid, an essential chemical used to produce methamphetamine, which is not on any Indian government watch list. This shipment was sent to a company called Corporativo y Enlace RAM, which is based in the Mexican state of Jalisco.

Corporativo y Enlace RAM faced scrutiny for its commercial transactions as well. According to a report in Milenio, Mexico’s National Intelligence Center (Centro Nacional de Inteligencia – CNI) investigated the company for allegedly diverting precursor chemicals to drug production networks associated with the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG. In response to an InSight Crime query about the case, Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office declined to comment.

InSight Crime also made several attempts to interview officials from the Indian Narcotics Control Bureau, the Ministry of Health and Family, and the Indian Embassy in Mexico, but did not receive a response.

Germany: The European Hub

The Algredo network worked in Europe as well. At least seven companies in Germany had a commercial relationship with MB Barter & Trading between 2016 and 2021, according to the Altana Atlas. These included chemical manufacturers, import-export companies, shipping companies, and companies working in the food industry.

The network sent numerous chemicals from Germany to Mexico during that time, including 48 tons of sorbitol, 443.5 tons of sodium carbonate, and 20 tons of hypophosphorous acid, all essential chemicals that can be used to produce fentanyl and methamphetamine but none of which were on German watch lists. The shipments departed from the German ports of Bremerhaven and Hamburg and arrived at the ports of Veracruz and Altamira in Mexico, the shipping data shows.

The companies did not seem to fit any specific pattern. Five of them operate in the city of Hamburg, in northern Germany. Another one is based in Kronberg in the state of Hesse, and the last one in Oberthal, a city in the western part of the country. Four of these seven companies are transnational and handle hundreds of clients across the globe. However, the rest are small companies that have only registered a handful of transactions with foreign partners. One of these, an import-export company, registered just six exports, three of which were made to companies in Mexico that regularly deal with controlled substances, according to the Altana Atlas.

These companies are part of the more than 2,200 chemical companies registered in Germany, making it the third-most important industry after automotive and machinery. Germany is also the chemical hub of Europe. In 2020, it led the continent in chemical sales and was third in the world, behind only China and the United States.

In Latin America, Mexico is one of Germany’s most important trading partners. During 2022, the country made international purchases from Germany totaling $17.6 million, $2.1 million of which were allocated to pharmaceutical and chemical products, according to data from the Mexican government.

Considering the scale of chemical production in Germany, its regulations of these substances are less stringent than in other countries. For example, chemicals such as methylamine and benzyl chloride — which are heavily regulated in Mexico since they are precursors and pre-precursors that can be used to produce methamphetamine — are subject to voluntary monitoring but are not listed as controlled substances in Germany. These types of disparities make the country attractive to criminal networks seeking to access these chemicals.

Still, Germany has robust legal frameworks regarding the companies producing, trading, and exporting these substances. The country’s laws are governed by conditions set by the European Union (EU), which require licenses, permits, transaction records, data on the parties involved, and pre-export notifications to control the flow of chemicals. Furthermore, according to the most recent US State Department’s International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), cooperation between the chemical industry and German authorities is a key part of the country’s chemical control strategy.

InSight Crime contacted the German Chemical Industry Association (Verband der Chemischen Industrie) to ask about this matter. The association said the chemical companies in the country are aware of the potential dangers associated with drug precursors and the responsibility they have if they handle them. In addition to working closely with authorities, they added that some chemical companies have taken the initiative to monitor and control the supply of such substances themselves, which includes conducting due diligence on their potential clients.

However, enforcing these regulations is more complex. In 2022, for example, the German government raided a company that made more than 30 shipments of precursor chemicals to Russia that could be used to produce biological weapons. The company made the shipments for more than three years without meeting export requirements.

Low visibility at ports is also a concern for irregular shipments. In a 2023 report about criminal activity at ports in the European Union, Europol noted that the ports of Hamburg and Bremerhaven were among the most vulnerable to criminal activity, along with Rotterdam in the Netherlands and Antwerp in Belgium. Among the reasons they cited were low rates of container inspection.

What’s more, during our research, InSight Crime did not find any criminal cases regarding German chemical exports from Europe to Latin America. And the German police and several European drug-market analysts said they were unaware of any cases involving German companies diverting precursors or chemical substances to Mexico.

Instead, they pointed to lax enforcement abroad. German police, for example, acknowledged past cases of diversion in which shipments had undergone the proper export due diligence in Germany but were ultimately diverted in the destination country. And although InSight Crime contacted the German Health Ministry and the customs authority, which are responsible for overseeing compliance with chemical regulations in the country, they declined to discuss the matter.

Without judicial cases, it is impossible to determine if German companies are aware that the chemical substances they are trading are being diverted to produce synthetic drugs. As previously mentioned, most of them are transnational companies dedicated to producing, distributing, and selling chemical substances across a number of industries, including mining, agrochemicals, veterinary care, and pharmaceuticals.

However, several German companies appear to have commercial relationships with Mexican companies that may have diverted precursor chemicals that were later used by Mexican drug production networks, such as MB Barter & Trading.

The Altana Atlas offers some examples. In 2022, a multinational from the United Kingdom and headquartered in Germany sent toluene — an essential chemical commonly used in methamphetamine production — to a company in Mexico that regularly deals with controlled substances. And between 2019 and 2022, another German multinational sent over 16.8 tons of benzyl alcohol — which is used as an essential chemical to synthesize methamphetamine — to a company in Mexico that also received frequent shipments of controlled substances. Benzyl alcohol is not on any German government watch list. And although toluene is heavily regulated, its use is widely known and the data about buyers is also available.

This potential connection between synthetic drug production in Mexico and German chemical producers also came up during interviews carried out by InSight Crime in Sinaloa in September 2023. An independent synthetic drug producer, for example, mentioned that he often buys fentanyl pre-precursors, such as 1-boc-4-piperidone — which is not on the German government watch list nor on any list of controlled substances in Mexico — from a chemical company in Germany. He declined to give us the name of the company but said it sends the products directly to properties that he temporarily rents in Sinaloa and the surrounding area. He added that representatives of the company gave him a guided virtual tour of the facilities in Germany while they were courting his business.

InSight Crime asked the clandestine producer if he thought the company was aware of the intended illicit use of the products.

“They never asked,” he said.

Germany also serves as a transit country for substances that may end up being used to produce illicit drugs in Mexico. In a series of indictments filed by US prosecutors against the Chapitos — the sons of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, “El Chapo,” who created their own criminal group following the extradition of their infamous father — authorities argued that companies in China often send precursors through Germany.

SEE ALSO: After Arrests, Extraditions, and Infighting, What Does the Future Hold for Mexico’s Chapitos?

The evidence for this was a conversation between the owner of a chemical company in China and a buyer in the United States, which was detailed in one of the indictments. In this conversation, the seller told the buyer that he usually ships precursors to Mexico from Germany, specifically so that Mexican authorities would not be able to identify China as the origin of the shipment.

Multilateral observers have also marked the trend.

“Transshipment countries are being used to hide the route … to not make it too obvious,” Martin Raithelhuber, a synthetic drugs expert from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), told InSight Crime.

As noted, suppliers of controlled chemical substances may opt for longer routes involving more countries to distract authorities. In addition to Germany, chemicals also move through the United States, as traffickers take advantage of huge shipping volumes, as well as loopholes that permit products to move through the country with minimal inspection.

United States: Ignore Your Customer

The United States is responsible for 11% of all chemicals produced worldwide, accounting for some $333 billion worth of products in 2022, according to the American Chemistry Council. Importers, exporters, producers, and distributors of controlled chemicals must be registered with the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). They must also provide information on the importer and their import licenses, and notify authorities of any suspicious transactions of substances that could be used illegally in the receiving country.

However, in practice, these requirements are not always met. Companies may fail to comply with the so-called “Know Your Customer” standards, which can allow synthetic drug producers in Mexico to source key chemicals from US companies.

That happened in the Algredo case. In addition to Pro Chemie New York, at least five chemical production companies located in several US states, including Illinois, Pennsylvania, Florida, and Indiana, traded with MB Barter & Trading in Mexico, according to the Altana Atlas. Most of these were large companies with subsidiaries in various countries, such as Germany, Mexico, and India.

According to the Altana Atlas, at least two of these companies sent chemical substances to MB Barter & Trading that can potentially be used to synthesize methamphetamine pre-precursors, including a benzaldehyde derivative, nitropropane, and potassium borohydride. These are not on any list of controlled substances. The other three companies sent various chemical substances with no current known illicit uses to the Algredos’ company, as well as plastic equipment for handling chemicals.

Pro Chemie New York, on the other hand, sold pre-precursors and essential chemicals to at least another dozen companies operating in central Mexico.

Still, it is difficult to determine the scale of the problem. None of the companies that sent chemicals to the Algredo network, for example, were sanctioned or prosecuted. In fact, InSight Crime found only two public judicial cases that illustrate this dynamic. And the DEA, which also issues sanctions for violations, declined to respond to an information request from InSight Crime regarding how many chemical companies have been sanctioned for violating procedures related to the diversion of chemical substances.

Given the lack of judicial and regulatory actions, InSight Crime, drawing from the Altana Atlas and our bespoke list of major chemicals, analyzed shipping trends from the United States to Mexico and identified a number of troubling patterns. More than 30 US-based companies — several of whom were decades old and had subsidiaries in numerous countries across the world — were frequently sending pre-precursors and essential chemicals to several small Mexico-based companies that appeared to be singularly focused on receiving these types of chemicals. The substances they were sending included acetic anhydride and toluene, which are categorized as Class II controlled substances by the DEA.

During our fieldwork, InSight Crime also found some evidence that US-produced chemicals are being used in clandestine drug laboratories. In October 2022, following an army raid of a methamphetamine laboratory in a rural area on the border between Sinaloa and Durango, we visited the lab with authorities and spotted, among other chemicals, a bundle of calcium chloride, which is monitored in Mexico but not in the United States. The essential chemicals were produced by the Laredo, Texas-based Vitro Chemicals, Fibers, and Mining. It is not clear if the drug producers accessed their products from a Mexican distributor or directly through a representative of the company. InSight Crime contacted company representatives but did not receive a response as of the time of publication.

Other news organizations, most notably Bloomberg, have also reported on US-produced chemicals being diverted for drug production in Mexico.

Sourcing chemicals in the United States was not the only way the Algredo network got its chemicals to Mexico. Some of the chemicals they imported to Mexico also transited through US ports. Authorities were able to identify four of these, and seized the substances at the ports of Oakland, Houston, and Miami, court documents say.

According to US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), approximately 11 million containers arrive at the country’s seaports annually. Another 11 million enter via land routes. Of these, only approximately 3.7% are inspected, according to the American Journal of Transportation. But some of the chemicals may have never even passed that inspection process. Instead, they could have been designated as in-bond. This is a designation used for containers passing through the United States on their way to a third country.

These products would have been moved to a special in-bond warehouse before being exported to Mexico. They are not subject to the same scrutiny as products entering the United States and are often less scrutinized when they arrive at their destination as well. A former diversion investigator with the DEA told InSight Crime that chemical shipments that first pass through the United States are scrutinized less when they arrive in Mexico due to the perception that US customs officials have strict controls monitoring such imports.

SEE ALSO: US Chemicals Help Fuel Mexico Drug Production: Report

The traffickers are aware of that perception. One clandestine operator in Culiacán told InSight Crime that, “If [a shipment] has already entered the United States, it’s less likely that they’ll check it here [in Mexico].”

He added that his suppliers of fentanyl pre-precursors often use the China-US-Mexico route for that exact reason.

InSight Crime made several attempts to interview the National Customs Agency in Mexico, as well as their customs officials at Pacific ports and international airports, but none of them responded to our requests.

This type of in-bond shipment from the United States to Mexico has grown exponentially in recent years. Citing the CBP, a December 2022 Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs report said the value of in-bond movements between the United States and Mexico went from $4.29 billion in fiscal year 2018 to $99.4 billion in fiscal year 2022.

The main reason for this shift in trade is the sharp increase in e-commerce warehouses in Mexico. Nonetheless, this poses a serious challenge for US authorities due to the limited information CBP receives about this type of cargo. Those exporting in-bond chemical shipments are exempt from providing certain information to authorities, such as the name of the chemical, its country of origin, or the consignee’s name. This is a concern US authorities have raised in the past.

Authorities in Mexico are also beginning to notice. In September 2022, the Mexican navy identified an in-bond shipment of a chemical pre-precursor that entered the country after first arriving at the US port of Long Beach, California. It was transported to Mexico via land through the border crossing in Laredo, according to a naval intelligence officer who spoke with InSight Crime. Although the officer did not specify the name of the substance, he noted that it had various legal uses, and the only reason it caught the attention of authorities was the unusually large quantities being imported.

By all appearances, traffickers are using similar methods to move chemicals through Guatemala.

Guatemala: Imminent Risk

Although the Algredo brothers did not rely on Guatemala for their criminal activities, the country has a long history of involvement in the flow of precursor chemicals for synthetic drug production in Mexico.

The most notable recent case occurred in late 2012 when Guatemalan authorities dismantled a methamphetamine precursor trafficking network linked to the Sinaloa Cartel. The operation began in September of that year with the capture of Ramón Antonio Yáñez, a convicted Sinaloa Cartel operative who had allegedly orchestrated precursor shipments through Nicaragua and Guatemala to Mexico since at least 2009. On the day of his arrest, authorities seized a methamphetamine laboratory and almost 100 barrels containing chemical substances. Over the next three years, they captured and convicted at least eight others involved in the network, including the former head of security at Puerto Quetzal, on the Pacific Coast, from where the chemical shipments were allegedly imported.

Further investigations by Guatemalan prosecutors and the United Nations-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional Contra la Impunidad de Guatemala – CICIG) found links between this case and political elites. The CICIG assisted Guatemala’s Attorney General’s Office in charging José Alberto Rizzo Morán, the mayor of the coastal town of Puerto de San José, his wife, and two of his brothers-in-law. Prosecutors argued that Yáñez had paid the mayor and his family network to facilitate the transit of precursor chemicals through the port. This allegedly involved front companies owned by the family and fraudulent commercial transactions. Rizzo Morán was never convicted and was absolved in 2019. Yañez, on the other hand, escaped Guatemala in 2017 after a judge released him on a technicality.

Since then, Guatemalan authorities have not prosecuted another major precursor trafficking case, according to information the Attorney General’s Office sent to InSight Crime. But law enforcement officials in the region believe that criminal networks continue to take advantage of Central American ports to import chemical substances before transporting them to Mexico for illicit drug production, according to InSight Crime interviews with an official from Guatemala’s National Civil Police, a prosecutor from Honduras’ Special Prosecutor’s Office for Organized Crime, and an official from Mexico’s National Guard.

Guatemala’s seizure data partly supports this assertion. Seizures of precursor chemicals in the country grew from 390 tons in 2012 to 1,409 tons in 2021, according to data from the Attorney General’s Office. It is worth noting that authorities do not disaggregate this data by type of substance, so it is difficult to determine if these chemicals were intended for methamphetamine or fentanyl production. It is also impossible to analyze any particular trafficking trends.

This lack of detail in law enforcement surveillance is coupled with lax chemical controls, suggesting that much of the precursor trade in the country can be conducted without sparking any regulatory or legal scrutiny.

Guatemala, for example, does not have any controls in place for five pre-precursors used to synthesize fentanyl, including benzylfentanyl, 1-benzyl-4-piperidone, 4-piperidone, propionic anhydride, and propionyl chloride. These are all heavily regulated or monitored in Mexico. Sodium cyanide and 1-phenyl-2-nitropropene (P2NP), two pre-precursors for methamphetamine synthesis, are also not included in any of the country’s chemical control lists.

“We have only recently started to implement mechanisms [to curb the flow of precursors], but from what we have been able to observe, chemical substances are introduced into the country via legally constituted entities … then they are diverted for illegal use,” an official from Guatemala’s National Civil Police told InSight Crime.

There are more than 830 companies in the country that are licensed to import and distribute chemical precursors and essential chemical substances. These companies are monitored by the Health Ministry (Ministerio de Salud), which is responsible for ensuring compliance with licenses, tracking the companies and the quantities used, and conducting periodic visits to verify the use of the chemicals. However, they have limited institutional capabilities, which poses significant challenges when identifying gaps or possible cases of diversion.

“I have only three people [under my supervision] and I am obligated to inspect [hundreds of] companies at least once a year. It’s impossible,” said an official from the Department of Regulation and Control of Pharmaceutical and Related Products within Guatemala’s Health Ministry.

What’s more, when misuse of controlled chemical substances is identified, penalties are lenient and limited to administrative punishments, according to health officials interviewed by InSight Crime.

InSight Crime also spoke with representatives of Guatemala’s Association of Chemical Manufacturers and Distributors (Gremial de Fabricantes y Distribuidores Químicos – GREQUIM), who said that the association has cooperated closely with authorities on precursor chemical management. However, the association faces the challenge of involving more companies in this practice. Of the 830 companies with licenses to import and distribute precursor chemicals, only 32 are part of GREQUIM.

Other countries in Central America, such as Honduras, face similar challenges, making them vulnerable to facilitating precursor flows to Mexico. Honduran health officials who spoke to InSight Crime mentioned that they only began profiling and inspecting chemical companies handling controlled substances last year. Meanwhile, chemical controls remain lax.

These types of factors allow criminal networks to continue diverting chemical substances without being subject to scrutiny. For example, in March 2023, Guatemalan authorities announced the seizure of 240 barrels of an unspecified fentanyl precursor in Puerto Barrios, on the Atlantic coast.

“The shipment was quite large, leading us to believe that it was not intended for consumption in our country but rather was in transit,” a Guatemalan police official, who was not authorized to speak on the record, told InSight Crime.

Authorities said the shipment had come from Turkey. But after a review of the paperwork revealed no red flags, the police official said the cargo was released.

Producers and distributors of chemical products in China also appear to be aware of these trafficking opportunities in Guatemala. In February 2024, InSight Crime contacted a seller of 1-boc-4-piperidone in China, a pre-precursor to fentanyl that is widely used by drug production networks in Sinaloa. When asked about the shipping method, the individual suggested the substance be sent through Guatemala. They argued it would reach Mexico “faster” that way.

The Conviction

After his arrest at the US law enforcement office in New York in September 2021, Javier Algredo was placed into custody and transferred to a detention center in Washington, D.C.

For a time, his company, Pro Chemie New York, kept working. In October 2021, it sent two shipments totaling 25 tons of anhydrous citric acid, a chemical that is not known to be used to produce synthetic drugs, to the port of Manzanillo on its way to Carlos Algredo’s company, MB Barter & Trading, according to the Altana Atlas.

MB Barter & Trading also remained active for another year and a half after Javier’s arrest. In January 2022, it ordered 22 tons of acetic acid from a Turkish company and 180 kilograms of a chemical reagent from China, according to the Altana Atlas. Acetic acid is monitored in Mexico, as it is a pre-precursor for methamphetamine production and can also be used as an essential chemical to produce fentanyl.

However, this would be its last large chemical purchase. By the end of 2022, the commercial focus of MB Barter & Trading seemed to have changed completely. During December, it made over 50 purchases from two companies in Italy for coffee machines, pasta molds, nuts, and hairbrushes. It also changed its address to Mexico City. The company’s last recorded transaction came in February 2023, but it is still listed as active in Mexican business records.

Meanwhile, Carlos Algredo went on the run. He was indicted in November 2020, but that indictment had been sealed until well after his brother’s arrest. At the time of publication, Carlos had not replied to InSight Crime’s requests for comment.

During his trial, Javier testified that he was only an intermediary for Carlos, who he said handled the paperwork and payments to their suppliers in India, China, and Europe. Other witnesses — his wife and his accountant — argued that he was “devoted to his family” and justified his assets as coming from “wise investments” he made with the salary from his job at the hotel chain.

In July 2023, a jury convicted Javier Algredo inside a District of Columbia courtroom for drug trafficking, conspiracy to manufacture illicit substances, and money laundering.

In February 2024, US authorities ordered the seizure of properties and bank accounts associated with Pro Chemie New York. InSight Crime requested comment from Algredo’s legal team and the prosecutors handling the case, but did not receive a response.

On February 23, a judge sentenced Javier Algredo to 18 and a half years in a federal prison in the state of New Jersey.

*InSight Crime Co-director Steven Dudley, as well as investigators Victoria Dittmar, Parker Asmann, and Daniela Valle contributed reporting to this article. Miguel Ángel Vega also assisted with field interviews.

Altana supports InSight Crime’s research into precursor chemical flows by providing access to the Atlas, a dynamic, AI-Powered map of global supply chains, as well as to its Counternarcotics Dashboard, an AI-driven model to flag narcotics trafficking risk within global shipment and business ownership data.