Along the US-Mexico border, the business of smuggling migrants has evolved from a close network of clans with expert knowledge of crossing routes and connections to their migrant clients to a booming industry closely monitored and taxed by organized crime groups.

One place where this is clear is Altar, Sonora, a dusty village about 100 kilometers from the Arizona border that has gone from an agricultural hub to a staging area for thousands of migrants trying to enter the United States.

On a recent visit to the border, InSight Crime took a trip to this part of northern Sonora. With less than 10,000 residents spread across some 4,000 square kilometers, Altar was once a quiet agricultural and ranching municipality. While the presence of these industries is still visible on the federal highway leading west out of town towards Caborca, the largest metropolitan area in this part of Sonora, the migrant economy was omnipresent.

After passing a dry riverbed, a series of modest stores lined the street across from the public plaza and the tall, white-walled, colonial-style Catholic Church that has towered over the main square for more than 100 years. On the day we visited, green, white, and red lights hung above the four columns surrounding the entrance of the church in preparation for Independence Day, which Mexico celebrates every September 16.

Inside one of the stores behind a row of hanging backpacks, vendors hawked camouflage sweatshirts and sweatpants for 300 Mexican pesos (about $15). In the back, hidden from view, merchants also offered camouflage booties for 120 pesos (around $6), which migrants can wear over their shoes to ensure they do not leave any tracks on the route through the desert.

This was our first glimpse of the new economy of Altar — the migrant economy.

***

We made our way to the Community Care Center for Migrants and the Needy (Centro Comunitario de Atención al Migrante y Necesitado — CCAMYN). The CCAMYN, which is funded entirely by the Catholic Church, save for contributions made by independent donors, has been operating in Altar since May 2001.

We met Father Prisciliano Peraza García. Peraza wore an oversized sombrero and aviator sunglasses to cover his round face from the unrelenting sun. His lightly faded blue jeans fell over dark leather boots, giving off the look of a cattle rancher. His short, stout stature was cut by a deep, booming voice that was at times difficult to comprehend.

We climbed into his car, a candy-apple red Jeep with a white, three-foot-high stuffed bear strapped to the spare tire mounted on the back. As we bounced around town, the father flashed a peace sign and a guttural “Aye!” to everyone.

Throughout, he pointed to casas de huéspedes, the small, makeshift motels that seem to blanket the town. Peraza said these mostly unlicensed motels emerged when migrants began asking local shops for a place to stay overnight. At their peak, he said, they numbered well into the hundreds. Now, he estimated there were around 130, in addition to about 20 hotels.

The casas de huespedes offer more than shelter. They offer food, clothing, and other technical items such as flashlights and GPS devices. Peraza said different networks of polleros, or human smugglers, have tight control over some of them. The migrants cannot venture on the street without permission or an escort. The danger is two-fold, Peraza explained: rip crews targeting migrants that might assault them or kidnap and sell them to other polleros, or other polleros who may kidnap the migrants and force them to pay to travel with them.

Still, over time, these establishments have become the most visible economy to emerge directly from the industrialization of migrant smuggling here. Along a dirt track in one neighborhood off the main highway, nightly rates were advertised on the facades for as little as 30 pesos per night (about $1.50).

Another offered the same services at a similar price across the street. But this is just the starting rate, Peraza said. Ten more pesos for a pillow. Another 25 for a mattress. Even more for a blanket. He said most migrants pay about 100 pesos (about $5) per night after all the costs are factored in.

***

On the other side of town, construction crews erected new structures to accommodate the migrants to come. This infrastructure didn’t always exist because the Tucson sector of US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) in southern Arizona — which covers Sásabe, the small hamlet through which migrants leaving from Altar most commonly pass — was not always a well-traveled smuggling route.

Throughout the 1980s, officers at this part of the southwest border with Mexico averaged around 45,000 “encounters” each year, among the fewest alongside the Big Bend Sector in west Texas. But, as the US government increased its enforcement efforts in the mid-1990s using aggressive “prevention through deterrence” policies, migrants increasingly turned to the desert.

At its peak in 2000, CBP agents in the Tucson sector recorded more than 600,000 encounters. These incidents have dropped off considerably, but by the end of 2022, there will be well over 230,000 encounters, the fifth-busiest such location on the border. The encounters are feeding into record numbers along the entire border, where, for the first time since US border patrol began keeping track, it registered over two million encounters in the 2022 fiscal year.

The creation and subsequent organized criminal control of Altar’s guest houses are a direct reflection of the changing face of those smuggling growing numbers of migrants in Mexico. But in Altar, migration also pays in other ways.

Criminal groups use recruiters to find migrants that need to be transported to Altar. InSight Crime spoke with individuals migrating from as close as neighboring Sinaloa and as far away as central Guanajuato. The retailers around town don’t just offer them camouflage. They also sell clothing, hats, metal canteens, and other supplies migrants may need before setting off into the desert.

Hired drivers traveling in what locals call benz, or mid-sized vans, are paid to make dozens of trips every day that bring in thousands of migrants. A gravel road on the outskirts of town near the municipal trash dump acts as the main thoroughfare, and Peraza says the local police don’t usually disrupt this flow.

There are also other, adjacent industries in Altar that have felt the boom in migration. Car dealerships, for example, have found steady sales of vans. Gas stations fill them with fuel to move migrants. If they break down, mechanics make sure the parts and tires are in good enough shape to traverse the rough terrain.

Local companies also provided the necessary cement blocks and materials for the building crews contracted to set up the now multi-level, cramped, unlicensed motels. Laundry services are employed to clean sheets, towels, and other garments. Food stands selling barbacoa tacos and bean burritos have more mouths to feed.

While waiting for another chance to cross, several migrants told InSight Crime how the agricultural industry has also come to rely on their labor — abundant and cheap — to harvest local crops like asparagus, once the mainstay of this region. Between 2015 and 2020, more than 75,000 Mexican migrants arrived in Sonora looking for work, according to Mexican government data.

Even local organizations like CCAMYN have benefited from the industrialization of smuggling migrants through Altar. Increased migratory flows mean more funds and support to provide shelter and other essential services.

In all, Peraza estimated that 95 percent of the community directly or indirectly relied on irregular migration, a number impossible to confirm yet difficult to dispute.

***

In Mexico, migrants have always meant money but not necessarily for large criminal groups.

In 2011, the researcher Gabriella Sanchez finalized her dissertation for Arizona State University, which included an analysis of 66 human smuggling cases in the United States and interviews with hundreds of migrants. It remains one of the most thorough empirical works on the topic in which she describes the loosely knit networks of mostly family clans who managed migration through corridors like this stretch of the Arizona-Sonora border.

These networks needed much of the same infrastructure that we found in Altar, but they did not necessarily work for or under the “cartels,” the catchall moniker authorities, policymakers, and journalists alike use when referring to large criminal organizations.

Sanchez punctuated her 2011 study with a startling conclusion: “Far from being under the control of organized crime, smuggling is an income generating strategy of the poor that generates financial opportunities for community members in financial distress.”

But is that still true now? It remains hard to discern with any certainty. In some border cities, halcones, or lookouts, working with organized crime groups scout migrant shelters for “clients.” These groups also require polleros to pay a cuota (fee) for every migrant smuggled and have even installed their own polleros to handle smuggling migrants.

“After the start of the drug war in 2006, organized crime groups in Mexico diversified and increasingly turned to other criminal activities for profits, especially migrant smuggling,” one lawyer, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of their work on the US-Mexico border representing migrants abused by authorities and crime groups, told InSight Crime.

Others, stretching from Tijuana and to places like Altar, say they have also seen a noticeable shift in the trade. Peraza, for instance, said large criminal groups now exert far greater control over the migrants, especially as the prices have soared in recent years. What was once a $3,000 to $5,000 trip, now costs anywhere between $7,000 and $10,000 and beyond, migrants and authorities told us. One Mexican migrant, who has been waiting in Altar for the past year, said he paid $13,000 to cross near Sásabe and then receive transport to Phoenix and finally Houston.

“Organized crime groups shifted or expanded from what may have been traditionally their focus in drug smuggling to also being [involved] in human smuggling because of its profitability,” said Victor White, co-director of the Justice Department’s Joint Task Force Alpha, which was formed last year to combat human smuggling and human trafficking.

Just how much large criminal groups like the Sinaloa Cartel, whose different factions control this corridor on the US-Mexico border, are taking from these operations is up for debate. Peraza said they collect a quota of at least $100 per migrant. This may not seem like much. But assuming, as Peraza did, that as many as 30,000 migrants pass through Altar a month, that is $3 million just from that quota, just in Altar, just in one month.

SEE ALSO: Human Smugglers Outsourcing Drivers, Wreaking Havoc on US-Mexico Border

“The larger organized crime groups realized there was big business in migration,” he said. “There’s less trouble [bronca] with migrants and much more money [than in drugs].”

Peraza and others InSight Crime spoke to along the border coincided with that sum, and some estimated it was far higher.

In addition, these criminal groups may have also usurped other criminal economies that were once under the purview of the mom-and-pop operations that Sanchez described in her dissertation. The so-called “cartels,” for example, charge $1,000 to experienced Mexican migrants for “permission” to cross the desert in small groups of four or five without guides.

They also appeared to be taking few chances regarding the quotas they expect from smuggling networks. In spite of the path being made almost impenetrable by the recent rains during monsoon season, at least six pickup trucks sat at the edge of a dirt road winding north out of Altar to Sásabe when we drove past in Peraza’s candy-apple Jeep.

Using a notebook and pen, two men logged the names of those who were about to embark on their journey north. Dressed head to toe in camouflage with their faces covered in scarves, around a dozen male passengers sat shoulder to shoulder in the bed of one of the pickup trucks.

***

At the starting point of the road to Sásabe stood three long, slender white crosses. Each had a date and a name.

For those on the other end of these elevated prices, there are few guarantees. With the United States’ policies of prevention through deterrence and ports of entry now closed to those seeking asylum, migrants have been pushed into ever-more dangerous crossing points in remote areas of the desert.

From Altar, it’s less than 100 kilometers to the US-Mexico border at Sásabe. But the route through here is treacherous, absent of water or cover to protect from the red-hot sun of summer or the frigid temperatures that arrive with nightfall.

Besides these costs and the northern Sonora desert’s unrelenting conditions, the migrants face other dangers, including the armed rip crews that extend throughout both sides of the border.

“We have one organization now knowing, ‘Hey, there’s a smuggling event [going] on [so] let’s take their load of [migrants] and now hold them hostage,’” Leo Lamas, the Deputy Special Agent in Charge in Tucson for Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), the investigative division of the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), told InSight Crime.

Back at CCAMYN, there are plenty of reminders of the risks. Passing through the doorway, tiny pamphlets sat atop a wooden dresser offering information so migrants better understood their rights, how to report abuses, and where they could find services to support them on their journey. A demand hung on the bulletin board above: “No More Deaths.”

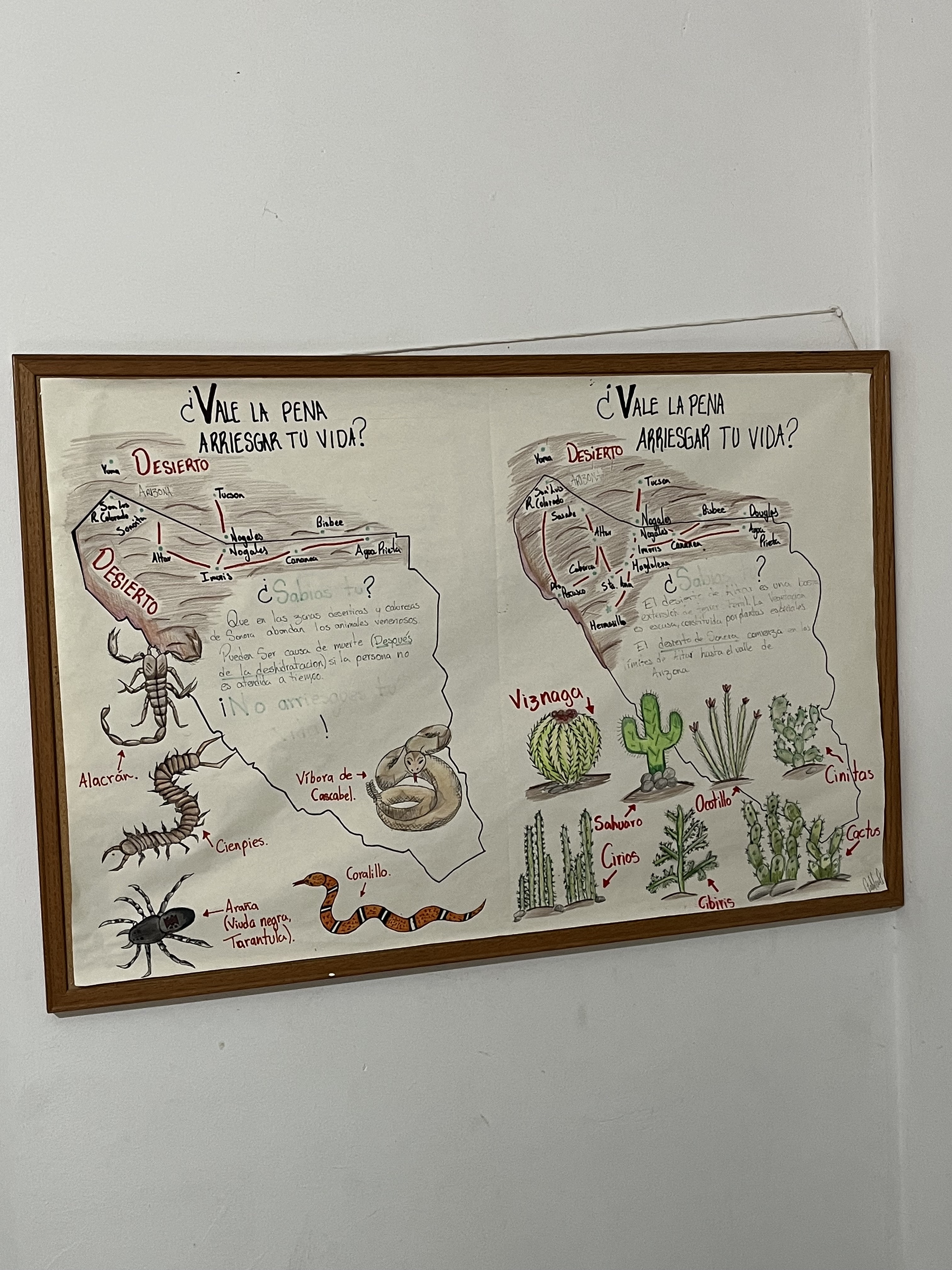

To the left of the table, a two-part diagram hung on the wall leading to the entrance of the primary room. The shelter used detailed handmade drawings to guide migrants through every kind of flora and fauna they could encounter crossing the desert.

“Is it worth risking your life?” the diagram asked.

In the dining area, a map of the southwest border separating Arizona and Sonora hung on a wall. A large cluster of tiny red dots was centered around one specific section of the desert in southern Arizona between Sásabe and Lukeville to the west. Between late 1999 and mid-2021, the majority of the almost 4,000 migrants found dead were located there, according to data collected by Humane Borders.

However, the true tally of migrant deaths on the US-Mexico border is likely far greater since these are just the bodies that advocates and local and federal authorities found — CBP only counts the deaths their agents encounter — before the earth swallowed any trace of them.

Still, deaths don’t seem to slow the human smuggling-industrial complex. As the sun sets, the CCAMYN cooks announced dinner-time. After the close to two dozen migrants at the shelter sat at their tables to eat, CCAMYN employees led a prayer.

Most of them were getting ready to leave in the coming days. Should they perish along these paths, it’s unlikely they will get a cross built to remember them, not even on a lonely Mexican road.