Mexico’s fast-tracked extradition of a top fentanyl trafficker to the United States and a months-long, underworld-enforced prohibition of fentanyl production suggest Mexico’s government and some of its most-targeted criminal actors may be trying to reset US-Mexico counternarcotics relations.

On September 15, Mexico’s government extradited Ovidio Guzmán López, a top leader of the Chapitos, one of Mexico’s most powerful criminal groups. According to multiple US indictments released in April, the group is the most prolific trafficker of the deadly synthetic opioid, fentanyl, to the United States.

Guzmán López will face trial in Chicago, where federal authorities at the Northern District of Illinois indicted him on nine counts related to controlled-substance trafficking, arms trafficking, money laundering, and continuing a criminal enterprise.

Known as “el Ratón,” or the Mouse, Guzmán López was arrested in Mexico in January during what was the government’s second try to corral the elusive son of the legendary drug trafficker, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera. Along with three of his brothers, Ovidio is considered a leader of the Chapitos, one of the central pillars of one of the world’s most powerful criminal networks, the Sinaloa Cartel.

A Reset?

The extradition follows months of tense public and private communications between the United States and Mexico, during which President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as AMLO, has consistently denied that Mexican criminal organizations synthesize fentanyl in Mexico, in spite of strong evidence to the contrary and surreptitious diplomatic messages from his own security forces.

The fentanyl trade has become a political touchstone in both countries, with some powerful Republican Senators calling for US military force to stem the trade. Fentanyl — sprinkled into fake prescription pills and legacy drugs — is responsible for tens of thousands of overdose deaths a year in the United States.

In this context, the extradition of Guzmán López appears to be part of an effort to mend relations. Sherri Walker Hobson, a former US assistant attorney who prosecuted numerous fentanyl cases in California, said it moved faster than cases she worked in recent years.

“I’ve prosecuted Mexican cartel members who were pending extradition in Mexico for years before their ultimate extradition to the United States, so this expedited extradition of Ovidio Guzmán López is definitely strategic and political,” she told InSight Crime.

Guzmán López was a prized target for US law enforcement. The US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) — in particular its administrator, Anne Milgram — made Guzmán López’s organization, the Sinaloa Cartel, the bogeyman in the battle against synthetic drugs. And in the US indictments, prosecutors blame the 33-year old for developing the trade beginning in 2014 — a dubious contention given that fentanyl did not hit the US market in any substantive way until 2015 and even then mostly seemed to come directly from China — and trying to monopolize it in the years that followed.

Notably, following the extradition, US authorities applauded the Mexican government.

“We thank our Mexican counterparts for their partnership in working to safeguard our peoples from violent criminals,” the White House Homeland Security Advisor Dr. Liz Sherwood-Randall said in one of many US government statements lauding Mexican efforts.

Sherwood-Randall’s statement also appeared to include a nod to numerous Mexican military personnel killed during the January capture of Guzmán López in a small town outside of Culiacán, Sinaloa, the heart of the Chapitos’ stronghold. The arrest operation came just over three years after an aborted effort to capture him in Culiacán, during which several people were killed and dozens injured as armed cartel members blocked bridges, burned cars, and threatened members of the families of the military based in the area.

Still, it’s not clear this extradition will placate US authorities, especially the more rabid politicians who appear poised to make Mexico-sourced fentanyl a major political issue during the 2024 elections.

What’s more, experts believe the extradition is the least the Mexican government can do.

“Is it good that Ovidio was captured and extradited? Absolutely,” Vanda Felbab-Brown, a Brookings Institution scholar who has long followed the fentanyl trade, told InSight Crime. “But I don’t believe it’s a fundamental reset in the relationship between the United States and Mexico. This is the minimum necessary to be able to demonstrate that there is cooperation.”

The Fentanyl Prohibition

The extradition of Guzmán López comes as criminal organizations in Culiacán, the epicenter of synthetic drug production, have taken extreme measures to halt the production and trafficking of fentanyl through Sinaloa, in what is perhaps an effort to ease government pressure.

Three fentanyl suppliers — one a commander of a large synthetic production group, one an independent purveyor and producer, and one local cook, all of whom spoke on condition of anonymity — told InSight Crime during fieldwork in Sinaloa in September that they halted production and sales several months ago. Although they said their bosses didn’t explain their reasoning, the decision came following Ovidio’s arrest in January and the release of the US indictments against the Chapitos in April.

The suppliers suggested the ban on the fentanyl trade and the judicial pressure on the Chapitos may have been related.

“I don’t know why [the production] stopped,” the purveyor said. “But I am guessing that it is an agreement, so they leave them alone.”

Meanwhile, the cook said he thought it was related to US pressure.

“The DEA is very pissed with Iván and Alfredo,” he said, referencing Ovidio’s brothers, Iván Archivaldo and Alfredo, the duo that forms the heart of the Chapitos.

Our reporting follows a June 13 Ríodoce article, which said that fentanyl producers in the state had received an order from the Chapitos to cease all production and trafficking.

Shortly after the Ríodoce report, authorities began discovering bodies on the outskirts of Culiacán. Some of these victims were found handcuffed, bearing signs of torture, and placed alongside hundreds of fentanyl pills.

The message conveyed by these killings was unmistakable: This is the consequence for anyone who continues producing and trafficking fentanyl in Culiacán.

Other killings were less obviously related to the fentanyl ban but for local purveyors of the drug were equally alarming. On September 8, for example, authorities found the dead body of Luis Javier Benítez Espinoza in front of a local health clinic with multiple bullet wounds, according to a Ríodoce report.

Known by his alias “14,” Benítez had a $1 million reward for information leading to his capture issued by the DEA for alleged fentanyl trafficking. The suppliers told InSight Crime they suspected that Benítez was killed because he was defying the ban.

The fentanyl suppliers interviewed by InSight Crime alleged that networks associated with Ismael Zambada, alias “El Mayo” — another pillar of the Sinaloa Cartel — were also enforcing this shutdown.

“Right now, everything is at a standstill; we cannot work,” the independent purveyor told InSight Crime.

A Surge in Disappearances

The implementation of this order has sparked a surge of violence and disappearances in Culiacán and the surrounding regions.

“Anyone who disobeys must be executed,” one criminal security chief affiliated with the Chapitos told InSight Crime, speaking under a strict anonymity agreement.

The security chief estimated that a minimum of 50 people have been killed for defying orders regarding the production, trafficking, and consumption of fentanyl. The commander who spoke to InSight Crime also said he thought that close to 50 people had been killed for defying the production order.

The security chief said he manages a group of 20 enforcers who spend their time identifying those defying these orders, carrying out their executions, and confiscating all their production materials, including precursor chemicals.

While some victims have been left in public places, the underworld sources consulted by InSight Crime said the majority have been murdered in remote areas and their bodies disappeared.

“We find nearly all the fentanyl cooks in the mountains,” the security chief said, implying they also leave their dead bodies in those areas. “There have only been a few in the city.”

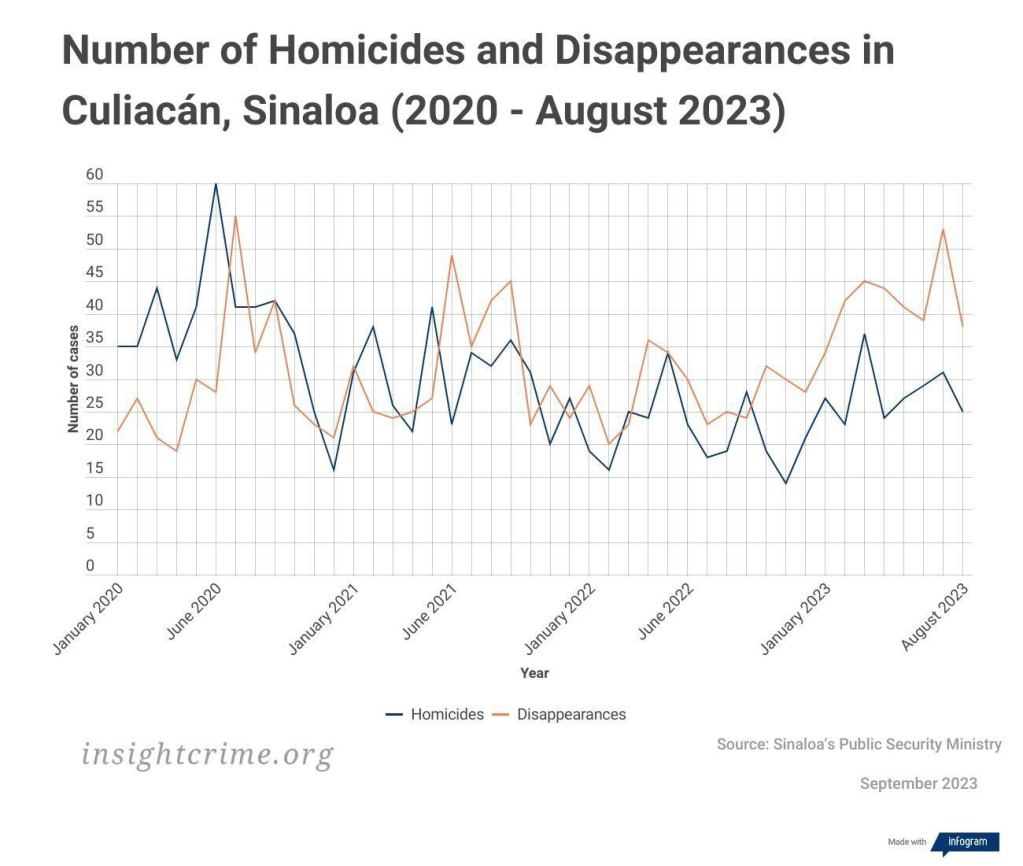

Statistics from the Sinaloa state government back their assertions. While the number of homicides has remained relatively stable compared to the first four months of the year, disappearances have surged, reaching a peak in July with 53 reported cases.

This corresponds with a pattern observed in Sinaloa over the past three years, where criminal organizations employ disappearances as a means to punish those who defy the rules related to drug markets, while striving to maintain control over homicides, so local politicians can tout their security successes.

*With reporting from Miguel Ángel Vega.