The hunt for “Memo Fantasma” had stalled once again. The name Guillermo Camacho did not register with anyone. Had The Ghost managed to wipe all traces of his real identity? Was he now living under a false name? Was he gone forever?

In 2017, without realizing it, InSight Crime hired the author of the El Espectador article which named Memo Fantasma and Sebastián Colmenares as Guillermo Camacho. Ana María Cristancho brought with her the information she had on Memo Fantasma and a keen desire to keep working on the story. In the aftermath of the publication of her article, another source had come forward anonymously, presenting herself as a woman who had had an intimate relationship with Memo Fantasma that had ended badly.

While Ana had been unable to verify the identity of the source, whom we shall call “Zara” (after the William Congreve play “The Mourning Bride”), she provided valuable information, all of which checked out over more than two years of investigation.

Zara’s first and perhaps most important nugget of information was that Guillermo Camacho was a false identity that Memo Fantasma had created to protect himself while he worked with the paramilitaries of the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC). He even had a false ID card with the name printed. She provided another name: Guillermo León Acevedo Giraldo. We were back in business.

*Drug traffickers today have realized that their best protection is not a private army, but rather total anonymity. We call these drug lords “The Invisibles.” This is the first article in a six-part series about one such trafficker, alias “Memo Fantasma,” or “Will the Ghost.” Read all chapters of the investigation here, or download the PDF.

Investigations were divided into several fronts: searching through all databases and company records for that name; scouring the records of the paramilitary peace process, the Justice and Peace Tribunals testimony; checking with Colombian and international law enforcement sources; consulting Medellín underworld players; and finally, speaking to former AUC paramilitaries.

Trusted Sources Go Silent

But doors began to slam very quickly. Some police sources, whom I have known for over a decade, suddenly refused to cooperate once the name Acevedo was mixed with Memo Fantasma.

“Not that one,” said one long-trusted police contact, “don’t ask me again.”

US law enforcement sources also went strangely quiet. One, whom I especially like and trust, told me this was one I might need to leave alone: “You could easily have an accident in Medellín, and no one would ever be able to trace it back to him.”

Another suggested that he was “protected.”

A senior paramilitary source, whom I will call “Héctor” and with whom I had a long history going back to 2000, also warned me off: “This is one of the few guys that scares me. He is connected at the highest level. He does not need bodyguards, he has the police. He is connected. This is a spiteful and vengeful man. I will not help you.”

SEE ALSO: After Prosecutor’s Murder, Will Colombia Protect Its Anti-Crime Crusaders?

There was no better luck with Medellín underworld sources. Many had heard of the alias Memo Fantasma and had heard he had been at a certain party with a certain member of the Oficina de Envigado but nothing concrete. “You need a photo,” one Medellín criminal source insisted. “Without that, you will not get anything.”

There was no criminal history for any Guillermo León Acevedo Giraldo and not a single source was prepared to go on the record about him. Once again, Memo had managed to wipe all trails leading to him. It seemed he had high-level protection, had penetrated elements of the Colombian police and might even have been a US informant. Once again, defeat stared us in the face. The Ghost seemed destined to remain invisible.

Until we were saved by a Colombian TV show.

On February 25, 2015, the popular “Séptimo Día” program dedicated an episode to the abuse of women, and how people react when they see women being abused in public. The show staged a fight between a couple in a cafe in Bogotá, then registered the reactions of people. Seated in the cafe with two others was a man with dark hair and his tie undone. As the actor began to abuse the woman he was with, the camera zoomed in (at 4:55 mark).

For just a couple of seconds, it focused on the face of a man enjoying his coffee and trying to ignore what was going on in the background. It just so happened that the show was very popular with a group of former paramilitaries, including some from the Central Bolívar Bloc (Bloque Central Bolívar – BCB) of the AUC. They would gather while in prison to watch the program. During this episode, one of them apparently pointed at the screen and cried “that’s Memo Fantasma.”

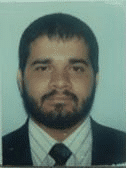

Ana María Cristancho came through once again. She not only managed to find the episode of Séptimo Día and the relevant segment, but a source got her a passport photo from what may now be a disappeared police file on a trafficker known as Memo Fantasma.

Suddenly, we had two pictures of Memo Fantasma. They were the same man. At the same time, a search of the Medellín and Bogotá Chambers of Commerce turned up a Guillermo León Acevedo Giraldo as a stakeholder in a company, Inversiones ACEM S.A. There was an office address in Bogotá: Carrera 14 Nº 85-68, office 408. All shareholders have to attach a copy of their identity card to the registration of any company with the Chamber of Commerce.

We had an official ID card and two photos. The Ghost began to take on a solid form and his story took shape.

Memo Cut His Teeth in the Medellín Cartel

Memo Fantasma was born in Medellín in 1971 and registered himself for his national identity card in the municipality of Envigado, part of Medellín’s urban sprawl. Envigado was where Pablo Escobar grew up and started his criminal career. Escobar set up a criminal structure in the municipal building of Envigado known as the “Oficina de Envigado,” a debt collection agency. Escobar would use the Oficina de Envigado to keep track of the debts that drug traffickers owed him for protection or logistics services. If anyone was foolish enough not to pay, the Oficina would contract the feared “sicarios,” or cartel hitmen. Much of the Medellín Cartel’s infrastructure was based out of Envigado.

Getting the story of Memo’s early days has been arduous. Most of the major traffickers of those days are dead or in prison in the United States. But Zara, the scorned lover, was able to get us started.

Memo was a scrawny kid with long hair when he started his criminal career as a teenager. He went to the United States to help receive drug shipments where, according to Zara, he worked with Fabio Ochoa Vasco.

Ochoa Vasco was one of the key members of the Medellín Cartel and responsible for much of the US end of its operations. Such was his importance that the United States put a $5 million bounty on his head. This was when he was handling an estimated six to eight tons of cocaine to the United States every month. Ochoa Vasco worked for Escobar and then his successor, Diego Murillo, alias “Don Berna,” until he turned himself in to US authorities in 2009. He was crucial to the development of routes into the United States via Mexico, and it seems likely that the young Memo learned the ropes from this top-level Medellín Cartel operative while making some important Mexican connections that were essential to his future criminal career.

Memo’s break allegedly came in 1992, when he was just 21 years old. Pablo Escobar was sat in a prison of his own making, dubbed “The Cathedral” in Envigado, having made a deal with the Colombian government and turned himself in once extradition had been taken off the statute books. Perched on a hillside overlooking Medellín, Escobar was getting angry, pacing around his golden cage. While he sat in prison, the rest of the Medellín Cartel was making money hand-over-fist, and he felt he was not getting his fair share of the proceeds.

SEE ALSO: Colombia Elites and Organized Crime: ‘Don Berna’

Before turning himself in, Escobar had placed much of his smuggling interests in the hands of senior traffickers, among them Fernando Galeano and the Castaño brothers. Galeano was one of the more prolific traffickers in the organization, and he was growing rich, protected by his head of security, Diego Murillo, alias “Don Berna.” The Castaños, whose father had been killed by Marxist rebels, were building their own paramilitary army to fight the guerrillas and becoming ever more powerful thanks to their cocaine earnings. Led by Fidel Castaño, alias “Rambo,” and his two brothers Vicente and Carlos, the Castaños were slipping out of his control, thought Escobar.

They were all summoned to the Cathedral to explain themselves. The Castaños refused to go, but Galeano went up the mountain, against the advice of Don Berna, hidden in a secret compartment in one of the trucks that supplied the prison. He was killed by Escobar in the prison, his body incinerated. Escobar then sent his sicarios to wipe out the Galeano clan and seize all its assets and drug business. Don Berna escaped. The killings sparked a civil war in the Medellín Cartel. The Castaño brothers allied with Don Berna and sought funding from the rival Cali Cartel, setting up a vigilante group called the PEPES (People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar). They set about intimidating, turning or killing Escobar supporters.

All this kicked off just as Memo Fantasma, sat in the United States, received a hefty drug consignment. Suddenly he had no boss looking over this shoulder, expecting payment.

“He was an associate of Pablo Escobar and the infamous Medellín Cartel, and ended up making off with a large load of high quality cocaine that he stole from Escobar and set up his own operation,” said Peter Vincent, formerly a senior US Justice Department official who worked in Bogotá from 2006 to 2009 and has deep knowledge of the Colombian drug world.

Memo suddenly went from a small-time player to the big leagues. He had the contacts in both the United States and Mexico, and now had the seed money to set himself up. He started dealing cocaine for himself.

Memo Builds Reputation After Fall of Escobar

As the Medellín Cartel war grew ever more brutal, Memo sat it out on the sidelines making money. In December 1993, Escobar was killed on a Medellín rooftop. The Medellín Cartel died with him, only to be replaced by the next generation: Don Berna in Medellín and the Castaños in the countryside of Antioquia and Córdoba departments, building up their paramilitary army and gobbling up drug trafficking real estate.

Towards the tail end of 1995 or early 1996, Memo was back in Colombia.

He was spotted in Medellín by Cruz Elena Aguilar, a former Colombian prosecutor and sister to one of the most feared enforcers in the Oficina de Envigado, Carlos Mario Aguilar, alias “Rogelio.”

“I heard my brother talking of a Memo Fantasma in 1995 or early 1996. I saw him once or twice around the same time, speaking to my brother,” she told us.

When shown the photos, she immediately said, “That’s Memo Fantasma.”

She added: “The only thing I know about him is that my brother had to collect a debt from him related to drug trafficking. Memo was kidnapped by him over this debt and was later released. He ended up becoming a friend of my brother.”

Three other sources who knew people in the paramilitaries and the Oficina de Envigado also told us of the relationship between Memo and Rogelio. Rogelio, it appears, had become Memo’s criminal Godfather.

SEE ALSO: Oficina de Envigado News and Profile

By this time Don Berna was running much of the Medellín underworld via the Oficina de Envigado. Rogelio was one of Don Berna’s most trusted lieutenants and at the heart of drug trafficking and the Medellín underworld. It may have been that Memo was acting as an independent drug trafficker without “protection.” The Oficina would routinely identify these traffickers and squeeze them. Nobody was allowed to operate in Medellín without paying their dues to Don Berna.

Memo Fantasma was now part of Medellín’s drug trafficking elite, and sources place him not only with Rogelio, but even alongside Don Berna at several meetings. At just 24 years old, Memo was moving in the highest circles of the Colombian drug world.

It seemed that he needed to get his hands on product. He had the network and the smuggling route to the United States via Mexico. But he was having problems getting enough cocaine to feed his buyers. So he decided to set up his own laboratory in the rural area of Yarumal, a town several hours north of Medellín.

We returned to Héctor, the former paramilitary commander, who became a little less reticent once confronted with the identity and photo of Memo.

“The Yarumal story I heard from a guy who later joined the paramilitaries, who had been there and knew Memo,” he told us. “This must have been around about 1997. Memo had set up a laboratory in Yarumal and was churning out cocaine. At this time the paramilitaries under the Castaño brothers were expanding out of their stronghold of Urabá and arrived in Yarumal. It seems Memo was acting without the permission of the Peasant Self Defense Forces of Córdoba and Urabá (Autodefensas Campesinas de Córdoba y Urabá – ACCU, the first paramilitary unit set up by the Castaños.) Or Memo might have actually claimed he was protected by the Castaños when he was not. Either way, he was summoned.”

Memo arrived to meet Carlos Castaño accompanied by Don Berna. He was given the option to pay for his “mistake” or to become part of the paramilitary franchise, thus officially gaining the protection of what was becoming one of the most powerful drug trafficking organizations in the country. Vicente Castaño, who handled the financial side of the business, introduced Memo to a powerful trafficker who had established himself in the municipality of Caucasia, a certain Carlos Mario Jiménez, better known by his underworld alias “Macaco.”

They were told by the Castaños to “conquer” the south of Bolívar province for the paramilitaries, long a stronghold of the Marxist rebels and home to hundreds of hectares of coca crops. Memo was to provide the money, Macaco the muscle. The Central Bolívar Bloc of the newly formed AUC was born soon after.

All of this was confirmed by José Germán Sena Pico, alias “Nico,” when he testified years later before the Peace and Justice tribunals set up as part of the paramilitary peace agreement.

“When it all started, the partner of Carlos Mario Jiménez [Macaco] was Sebastián Colmenares, alias Memo Fantasma. And when they were given the zone of southern Bolívar, more connections arose between Vicente Castaño and Sebastián Colmenares than with Carlos Mario Jiménez. So the links Memo oversaw were all to do with drug trafficking,” said Sena Pico.

The investigations into Memo’s criminal career were moving swiftly, but we wanted something on the man himself. The company registration of ACEM S.A., which gave us Memo’s identity card, also provided a wealth of other clues, including other investors. One of them, Catalina Mejía, whose Colombian ID card was also included in the company registration, turned out to be his wife or long-term partner.

While Memo had managed to wipe all traces of his personal life, his wife was from a prominent family in Medellín, which owned a big furniture business and was part of the city’s social elite. Penetrating that circle was not hard, and soon we found a relative, whom we shall call “Olga,” who could shed light on how the young Memo was not only intent on building up his business, but also looking to reinvent himself socially.

“It was clear he was of humble extraction but he always dressed well, usually in European suits,” Olga said, delicately stirring a coffee at a cafe in Medellín’s exclusive El Poblado district.

When confronted with the notion that Memo was a powerful drug trafficker known as The Ghost, Olga showed no surprise.

“He has plenty of money and is a very calculating man. I believe that he planned to find someone socially acceptable who could give him a leg up, introduce him to the right people and allow him to move freely among high society,” she said.

The Ghost was now positioned at the highest levels of the drug trade and the social world in Medellín. His ambition was to go much further.

*Investigation for this article was conducted by Angela Olaya, Ana María Cristancho, Laura Alonso, Javier Villalba, Juan Diego Cárdenas and María Alejandra Navarrete.