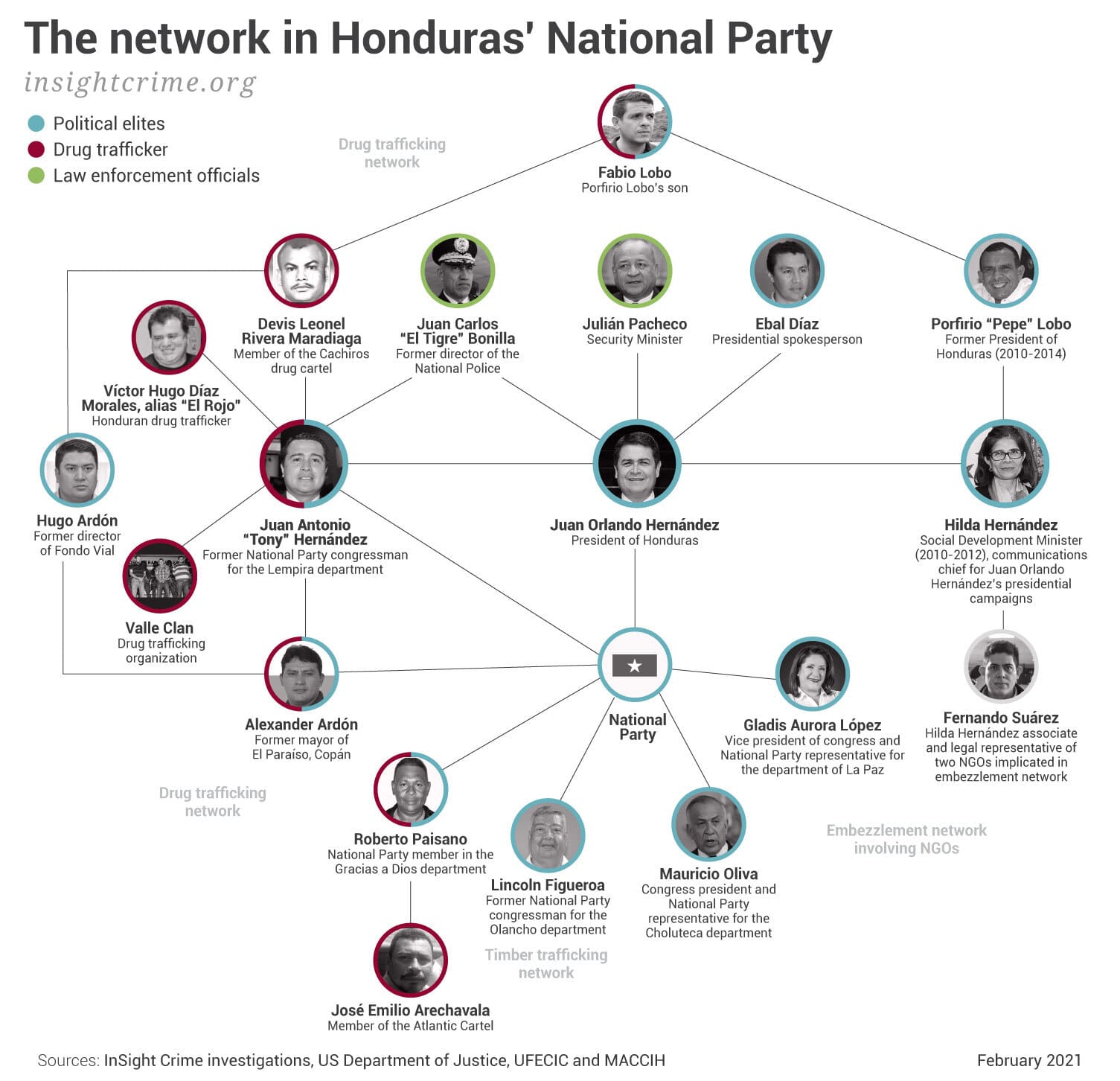

The party that has governed Honduras since 2010 has become a federation that welcomes politicians and officials involved in criminal businesses ranging from timber to drug trafficking to the misappropriation of public funds.

An informant working in the western department of Lempira looked at General Leandro Osorio and spoke: “I know a place where there are drugs.”

It was mid-January 2014 and Osorio was chief of intelligence for Honduras’ National Police. Osorio, who would later make some startling declarations about the case, asked for evidence and the informant promptly produced photos of what appeared to be a greenhouse hidden in the mountains.

The informant also provided the general with the coordinates but warned that the drugs and some of those who worked there were protected by a high-ranking police official and a very powerful politician.

The greenhouse was close to La Iguala, a small village embedded in the mountains of Opalaca, some four hours by car and another hour and a half on foot from Tegucigalpa. It was close to Gracias, the capital of Lempira and home of the Hernández clan.

The clan was known for its small coffee plantations and its political ambitions. Juan Orlando Hernández is the head of the country’s ruling National Party and Honduras’ president since 2014. His brother, Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, was an alternate congressman at the time. His other brother was a colonel in the army.

But Osorio was determined to check the informant’s report, so after midnight, January 31, 2014, without notifying his superior officers in Tegucigalpa and giving only vague information to the Attorney General’s Office, Osorio and an elite police unit began driving towards the mountains.

“Only I knew what we were going to do,” Osorio recounted to InSight Crime years later in Tegucigalpa. “I only told the prosecutors that we had information about a place where there were supposedly drugs.”

SEE ALSO: Border Crime: The Northern Triangle and the Tri-Border Area

At 5 a.m., Osorio and his unit had driven as far as they could, descended from the truck and started making their way on foot. It was a difficult climb, Osorio said, a kilometer-long march upwards through thick brush and forest.

But when they arrived at the coordinates, they could see the coca and marijuana plants, thousands of them, surrounding what looked like a greenhouse but was really a small laboratory. They combed the fields and the laboratory where they found a .22 rifle, two large generators and several barrels of diesel fuel. And they arrested two suspects who appeared to be tending to the fields – a Honduran and a Colombian, the same ones who the informant said had top-cover.

In total, the general and his unit found some 1,800 poppy plants and 800 marijuana plants. The general also told InSight Crime they found some 6,000 coca plants.

“It was close to a hectare and a half of forest,” he said.

InSight Crime corroborated Osorio’s account with documents from the United States Justice Department. These documents, which appeared years later in a separate investigation, make references to the laboratory, the police protection it was receiving, and the alleged connections between Tony Hernández and the instalation in La Iguala. An Attorney General’s Office official and a member of the National Police intelligence branch also confirmed to InSight Crime that authorities were investigating the instalation and the two men who were captured during the raid. The police intelligence officer added that Hernández had been named in the investigation.

Osorio said he packed some of the plants in his vehicle to show as evidence of his find and burned the rest, which he said was standard operating procedure. Later, he went to Gracias to inform the national police and the Attorney General’s Office based in Lempira’s capital city. That’s when his problems started.

Funding the Political Project

Long before Juan Orlando assumed the presidency and his brother Tony began moving drugs through the country’s main cocaine trafficking routes, their sister Hilda Hernández found her own path within the ranks of the National Party. She started when she was 36, during the administration of President Ricardo Maduro (2002-2006), but her political career really took off when she served as the Minister of Social Development and Inclusion under President Porfirio Lobo (2010-2012).

As minister, her job was to coordinate the disbursement of public money for social programs. Her post gave her the tools to create a powerful political juggernaut: a network of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and front companies through which she could channel government-allocated resources. These NGOs and companies signed contracts with the government for social development projects. Some of the money went to those projects.

However, according to investigations conducted by the Special Prosecutor’s Unit Against Impunity and Corruption (Unidad Fiscal Especial Contra la Impunidad de la Corrupción – UFECIC) and the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (Misión de Apoyo Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad en Honduras – MACCIH) — the two entities that were entrusted to investigate corruption in Honduras – some of the money was diverted to politicians and political campaigns, including to that of Hilda’s brother, Juan Orlando, during his presidential bid in 2013.

Specifically, a high-ranking government official who worked on the investigation told InSight Crime that Hilda created around 279 foundations. From those, investigators think as much as $360.6 million in public funds may have been misappropriated.

From the beginning, it was a family affair. Hilda requested money for projects through what was known as the Departmental Development Fund. The fund was controlled by Congress, whose president at that time was her brother Juan Orlando. Congress authorized for the funds to be distributed to the foundations. That money was diverted to the personal accounts of politicians or collected in cash by Hilda’s associates.

According to an investigation by Univisión, some projects were small (like the distribution of school supplies) and therefore difficult to trace. In other cases, contracts were given to NGOs for things like pesticide and fumigation, when the NGOs specialized in youth development. According to Univisión, 360 former and serving politicians and government officials benefited from this scheme.

“All the funds were stolen,” an official who worked on the investigations told InSight Crime in reference to the money misappropriated by the ministry.

The case was so big that authorities split it into parts. A document presented by MACCIH and UFECIC to the Honduran courts in June 2018 mentioned two NGOs, Dibattista and Todos Somos Honduras (We Are All Honduras), which they claimed misappropriated $12 million. The money, the investigators said, went to political campaigns of the National Party and the Liberal Party in 2013. The case came to be known as “Pandora’s Box.” But these court documents did not mention the names of Hilda or Juan Orlando Hernández.

It was only after Fernando Suárez, one of Hilda Hernández’s associates that collected payments for her, turned himself in to authorities in November 2018 that the family was connected. Suárez — who was the legal representative of the two foundations mentioned by the MACCIH and UFECIC — said that a part of these funds was used to support Juan Orlando Hernández’s political campaigns.

Suárez’s testimony linked two presidents to the corruption scheme. According to Suárez, under Porfirio Lobo’s administration funds were funneled to the NGOs. Once the funds were deposited in the foundations’ accounts, the money was withdrawn.

“It was very simple: The money was withdrawn in cash and taken away in vehicles from the secret service,” Suárez told the authorities, referring to Lobo’s presidential guard.

It’s not clear what happened next to the money, but the prosecutors say the money went to both to private pockets of politicians and to the National Party’s coffers. For his part, Lobo has said that Suárez is a “fabricated witness”.

Additionally, Suárez said it was Hilda Hernández who instructed him to have the payments directed to her brother’s campaign. She never withdrew the money or made the payments herself, so that her name would not appear on any documents, investigators said. Nevertheless, according to Suárez, once the funds were in the National Party, Hilda was the person who held the purse strings.

The presidential campaign appeared to be tight, and Suárez said the funds “were indispensable” for Hernández’s 2013 campaign. Hernández won with 37 percent of the vote, a larger margin than expected.

Meanwhile, another even more nefarious family project, was taking form in the countryside, near the border with Guatemala.

The Narco Connection

At the beginning of 2014, as Osorio and his elite police unit were making their way through the thick brush towards the coca, poppy and marijuana fields in La Iguala, the drug trafficking map in Honduras was experiencing some important changes. That year, the country’s two most important cocaine trafficking groups suffered heavy blows when their leaders turned themselves over to the United States or were captured and later extradited to the US to face charges.

At the same time, according to United States prosecutors, Antonio “Tony” Hernández, the president’s brother and an alternate congressman, tried to take advantage of his political connections to position himself as a top drug trafficker in Honduras. He never quite succeeded, but between him and his powerful family, they established a sort of federation with various political leaders and government officials that supported the legal and illegal operations in their territories.

According to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and US prosecutors, Tony was working with his siblings, Juan Orlando and Hilda Hernández, who authorities say were facilitating his drug trafficking enterprise.

From Gracias, Tony made his way. While his notoriety has grown in Gracias and elsewhere in the country, an old local politician, whose family also is considered part of Honduras’ political power, recalled Tony as an affable type, who was known in Gracias for selling meat near the soccer stadium. Those days in this city surrounded by mountains must now seem long gone.

Perhaps due to its proximity to Lempira, the Hernández family’s cradle of political power, Tony focused his operations in the neighboring departments and the border with Guatemala, where historically cocaine had found its North-bound path. There, in the departments of Copán, Santa Bárbara and Ocotepeque, a territory marked by fierce territorial control exercised by the clan of the Valle Valle family and others, Tony started his quest. His first important alliance was with Alexander Ardón, the mayor of El Paraíso, Copán, and a partner of the Valles.

During this period, Tony was “an errand boy,” a former military intelligence official told InSight Crime, but then he started working with Víctor Hugo Díaz Morales, alias “El Rojo.” Rojo was a key player in the drug world, and through him, Tony Hernández began participating more directly in the business. In return, Rojo told US prosecutors that he gave money to Tony to finance Juan Orlando Hernández’s congressional campaign in 2005.

In 2010, according to US court documents, Tony told Ardón that he wanted to be independent of the Valle Valle family. And both agreed to receive cocaine shipments in La Mosquitia, a jungle region in the northeast of Honduras. Some of them were later stamped with the initials, TH, then sent to the US.

It was about then that Osorio entered the drug laboratory in La Iguala. Before descending the mountain, Osorio interrogated the Colombian that he had arrested at the laboratory. The Colombian told him he had been paid $25,000 to take care of the place. He did not say who had hired him, but Osorio got an inkling that it was someone important as soon as he told prosecutors and police about the case.

“It was a nerve-racking place where the prosecutors did not want to take on the cases of those arrested, and the judges did not want to collaborate,” Osorio recalled, referring to his visits to the police and prosecutors’ offices in Gracias.

At some point, while debriefing other authorities, another policeman reiterated what the informant had told Osorio, only this time with more specifics: that Osorio was dealing with well-connected networks, which included the National Police Commander, Josué Constantino Zavala Laínez, who was assigned to the area, and Tony Hernández.

Osorio returned to Tegucigalpa and informed his bosses, but it only got worse. The Colombian was released, Osorio found out, and the investigation into the drug laboratory was halted. Prosecutors also refrained from looking into Tony Hernández’s possible connection to the plantations. Osorio was transferred and later discharged by the police altogether.

“My discharge goes back to that operation in La Iguala, and from other similar operations where I could not count on the support of the military or prosecutors. There is not a single allegation against me for human rights violations, nor for anything else,” he told InSight Crime.

For Osorio, the irony was thick. In October 2018, Tony Hernández was arrested in Miami on drug trafficking charges. A year later, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) requested information about the presumed “criminal activity of [Tony] Hernández Alvarado and/or his associates,” including one of his purported partners: Police Commander Zavala Laínez, the same one who had handled the case of the laboratory in La Iguala. According to a witness cited by the DOJ, Zavala Laínez met with Tony Hernández in order to coordinate activities at the laboratory. In one of these meetings, Hernández “thanked” Zavala Laínez for his protection, the documents say.

The scheme was also political. According to the US prosecutors that later formally accused Tony, the Hernández family and other co-conspirators used drug trafficking funds to “finance the campaigns of candidates from Honduras’ National Party (PN), including presidential campaigns in 2009 and 2013, so as to maintain its power and political influence. As a result, in 2014, the accused was not only a violent drug trafficker, capable of moving several tons [of drugs], but also a congressman.”

Tony was not the National Party’s first connection to transnational drug trafficking. Before him, there was Fabio Lobo, the son of President Porfirio Lobo, who was sentenced in 2017 to 24 years in prison on drug trafficking charges. Court files said the Lobo asked for more money to pay Julián Pacheco, the army general-turned security minister that, according to court testimony, provided protection to a convoy transporting drugs to the border with Guatemala. Pacheco, who is still President Hernández’s security minister, was also linked to Tony’s enterprise. He dismissed the allegations as lies, saying they were made by criminals who want their sentences reduced in the United States.

In 2019, Tony Hernández was convicted of drug trafficking in the United States.

Continued Drug Trafficking Connections

At the heart of criminal activities in Honduras is a symbiotic relationship between criminals and some high-level politicians. According to court filings by US prosecutors, the quid pro quo with the Hernández family, for instance, was an agreement with President Juan Orlando Hernández not to extradite some criminals in return for financial support for his party and his family. The president has denied these claims and points out that he has extradited numerous drug traffickers to the US, including supposed allies of his brother, Tony.

Nonetheless, US and Honduran investigators say the financial support from criminals helped Hernández win the presidency, once by a legitimate popular vote in 2013, and once under very dubious circumstances four years later, when, following a suspicious power outage after the vote, results shifted wildly in his favor to overcome a deficit. Although international observers from the Organization of American States later declared his 2017 re-election was obtained under suspicious circumstances, Hernández held on to the presidential palace.

In the meantime, some party leaders continue their close relationship with drug trafficking, in spite of Tony Hernández’s conviction and the near constant diplomatic chatter about President Hernández’s own relationship with traffickers. “The level of penetration of drug trafficking in the political world in Honduras continues to be very high,” one Latin American diplomat, who worked with MACCIH until the end of 2019, told InSight Crime.

One example of this configuration is in Gracias a Dios, in an area known as La Mosquitia, a sparsely populated jungle along the coast that borders the northeastern part of Nicaragua. Here the limited presence of the Honduran state combined with the difficult topography – mountains, swamps and desolate coves – have made the Mosquitia a prime respite and staging area for large cocaine producers in South America.

For years, these routes were dominated by the Atlantic Cartel. The cartel’s power grew largely thanks to its connections with, among others, local political leaders like Roberto Paisano Wood. Paisano Wood was the National Party’s strongman in Gracias a Dios for years, according to government sources as well as a political leader in La Mosquitia interviewed by InSight Crime.

“Nothing happens here without him knowing about it,” said the political leader, who asked for anonymity given the continued strength and danger the criminal networks posed.

Paisano Wood and his brother, Seth, were also trafficking drugs, according to an agent in the Honduran military intelligence unit who was based in La Mosquitia until 2018. The brothers were linked to José Emilio Arrechavala, one of the leaders of the Atlantic Cartel.

In October 2019, authorities arrested the brothers and charged them with money laundering. Specifically, prosecutors said the family was “an organization dedicated to drug trafficking that has its center of operations in Gracias a Dios.”

Political Party or Criminal Conspiracy?

More criminal enterprises have emerged around National Party — from environmental predators in the northern departments of Olancho and Gracias a Dios to local party leaders implicated in massive misappropriation of government funds.

Hundreds of kilometers from La Mosquitia, in the southern department of La Paz, for example, Gladis Aurora López has built her own fiefdom. López is a congresswoman and vice president of the Congress. She has also been listed by the US Treasury Department as someone who has “credibly alleged to have committed or facilitated corruption.”

Most notably, she was one of the politicians that benefited from the networks siphoning state resources for her own political campaigns. An official at the Attorney General’s Office told InSight Crime that the congresswoman’s husband was connected to Pandora’s Box case and that her daughter and her husband were connected to a related corruption case.

López’s husband is the administrator of at least two hydroelectric dam projects in La Paz that have also sparked controversy. An independent investigation by Global Witness linked the congresswoman to the violent repression of environmentalists that protested the construction of the dams, which obtained questionable permits and allegedly ignored indigenous groups’ protests of the massive projects, according to Global Witness.

InSight Crime tried to contact López to get a statement in response to these accusations but did not receive any response.

In Olancho, criminal networks dedicated to illegal logging and timber trafficking have also settled in the area thanks to the political power of some of its members. In the city of Catacamas, the mayor and former national congressman Lincoln Figueroa has been investigated for his alleged participation in illegal timber extraction networks in the neighboring mountains. In July 2011, his name was listed in an Inter-American Court of Human Rights report (Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos – CIDH) for his suspected involvement in the murder of an environmental activist in Olancho.

Since then, environmentalists and political opponents have linked Figueroa to illegal logging. Figueroa says the accusations against him are related to quarrels between political parties. And while various municipal environmental commissions in Catacamas have also investigated him, he has never been formally accused of a crime.

Other investigations in party officials’ illicit activities have also fallen short. After the Hernández family was connected to the Pandora’s Box case, the UFECIC and MACCIH began investigating the Honduran president. In the end, however, the Honduran judiciary buried the Pandora’s Box case. Shortly thereafter, in early 2020, the Hernández administration dismantled the MACCIH.

Consolidating Power

Tony Hernández’s conviction rocked the president and his party, and for a moment, he teetered. But Juan Orlando quickly regained his balance, with help of some of his closest allies, among them Mauricio Oliva, a leader of the National Party who is the president of Congress.

Oliva played a key role in dismantling MACCIH and, according to a source from the Attorney General’s Office, he helped push through reform of the penal code that limits the functions of the prosecutors to investigate corruption cases.

Oliva had his own ghosts in the closet. He was investigated by MACCIH and UFECIC for corruption, and a recent investigation by the media outlet Expediente Público found that a front man for the drug trafficking organization known as Los Cachiros had transferred four properties worth over a million dollars to him and his relatives.

But there are no known investigations into Oliva or President Hernández. In fact, there is currently very little political opposition to National Party. Opposition parties are divided, and civil society resistance has become much less visible.

UFECIC was also debilitated. A source in the Ministerio Público told InSight Crime that, after changing its acronym to UFERCO, officials of the unit have had their salaries cut and the staff was reduced, tripling the length of time it takes to do investigations.

“Juan Orlando has never been so strong,” a former MACCIH official told InSight Crime.