Seated at a plastic table inside a women’s prison on the outskirts of Honduras’ capital Tegucigalpa, Erika Bandy’s lips trembled as she spoke about her husband.

“In his last message to me he said that he knew that they were going to kill him and that if he lost his life, he begged me to tell everything I know publicly to save my own, to not stay quiet,” said Bandy, with a fearful, yet determined look. “He regretted having maintained his silence.”

This article is part of a special series detailing the rise and fall of former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was convicted on drug charges in the United States. Read the other articles in the series here.

A few weeks before Bandy met with InSight Crime reporters, on October 26, 2019, gang members had brutally murdered her husband, Nery Orlando López Sanabria, inside a maximum-security prison in northwestern Honduras, shooting him several times and then repeatedly stabbing his limp body.

The killing came soon after drug ledgers discovered in June 2018 in possession of Bandy and López were used by US prosecutors to help convict a brother of then-Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández on drug trafficking charges in a New York federal court.

Now, more than four years later, the ledgers will once again be presented as evidence in a drug trafficking trial – this time against former President Hernández – set to begin on February 12 in New York’s Southern District.

SEE ALSO: InSight Crime Series – The Downfall of Honduras President Juan Orlando Hernández

Prosecutors accuse Hernández of accepting millions of dollars in bribes from drug traffickers and overseeing a “narco-state” while president. The murder of López was intended to prevent his potential cooperation against Hernández and others, according to the indictment.

In a case built primarily upon the testimony of former drug traffickers who are now cooperating witnesses, the drug ledgers are a crucial piece of evidence.

Hernández has denied the allegations, citing his cooperation with the United States on anti-narcotics and immigration policies and his role in the passage of a constitutional amendment that paved the way for the extradition of Hondurans on drug trafficking charges. He was extradited to the United States just months after leaving office in January 2022.

Bandy – perhaps the only person other than López who could have definitively interpreted the contents of the ledgers – ultimately met a fate similar to her husband. But before she died, she spoke with InSight Crime in a previously unpublished interview.

InSight Crime interviewed more than twenty sources, including confidants of López and Bandy, and obtained numerous judicial files related to the couple, as well as a full copy of the drug ledgers. The reporting tells the story of how the ledgers fell into the hands of the authorities, and why López and Bandy feared they would be killed for their connection to the evidence that could prove key in Hernández’s upcoming trial.

Beginnings

Wearing a black blouse with a light blue cardigan and large, golden rings that swung from her ears as her body shook, Bandy recounted in the 2019 interview how she met López. A decade earlier, in 2009, the pair had a chance encounter while visiting a law firm. At the time, López sold used cars. Bandy was a 26-year-old widow with two children. Her first husband had been kidnapped and murdered the year before in a crime that was never solved.

López was from a family of peasants, while Bandy was from well-to-do landowners. They married in 2010 and Bandy gave birth to twins the year after that. But a quiet life in the suburbs was not in the cards.

By 2012, López was a large-scale trafficker, according to a US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) affidavit for his extradition. That same year, he met Hernández and his brother, Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández for the first time when they were campaigning, Bandy said. Juan Orlando was revving up his campaign to win the National Party’s nomination for president, and Tony was seeking a seat in Congress.

US prosecutors accuse Juan Orlando of accepting millions of dollars from traffickers during the campaign in exchange for protection from law enforcement, propelling him to victory in November 2013. Bandy did not say if she and her husband also made illicit campaign contributions, but Tony Hernández became a regular figure in their lives.

They met at campaign events, including at a dinner for the National Party held at a home of Alexander Ardón, another drug trafficker and National Party politician, Bandy said. Ardón would later become a star witness for the prosecution after turning himself into the DEA in March 2019, and is expected to testify against Juan Orlando Hernández.

SEE ALSO: How an Ex-Mayor Could Bring Down the Honduras President

Tony Hernández also visited the couple at their ranch. “I asked [López] who was coming,” Bandy recalled. “’A friend from the campaign,’ he said, without revealing the name. Then a helicopter arrived. I thought it was something to do with women. [Tony Hernández] got out wearing a white hat.”

“He offered my husband the chance to run for mayor or legislator,” Bandy said.

Villagers who lived near one of López and Bandy’s ranches in the Honduran department of Santa Barbara, along the mountainous border with Guatemala, reported seeing Tony Hernández with López on at least two occasions, according to a law enforcement official and another source who spoke on condition of anonymity.

DEA On the Trail

In November 2014, a drug bust gave López and Bandy a scare. Authorities intercepted a Mercedes Benz fuel truck carrying 351 kilograms of cocaine inside the tank near a ranch owned by the couple. The operation was led by members of an elite Honduran counternarcotics force that works with the DEA called the Special Investigation Unit (SIU).

According to an affidavit for the extradition of López and other co-conspirators, the shipment had been sent by plane from Venezuela, making landfall in the remote Honduran region of the Moskitia. The DEA was alerted of the shipment by cooperating sources who had infiltrated the drug trafficking network in South America. Only the driver was arrested, but the seizure no doubt set off alarm bells for all involved.

The next year, López hatched an elaborate plan to fake his own death, staging a funeral with a priest held at gunpoint. A photo of him lying inside a casket circulated on social media to complete the hoax. He corruptly obtained a death certificate and adopted a new identity, calling himself Magdaleno Meza, and underwent plastic surgery, altering his nose, hairline, jaw, and closing his dimples, recalled Bandy.

But the ruse did not work for long. In August 2016, US prosecutors indicted López under seal along with four Colombian and Venezuelan co-defendants. Soon after, the SIU conducted a search of properties linked to López and Bandy, and sent a request to the National Registry of Persons asking for records pertaining to both López and Meza, according to case files obtained by InSight Crime. The photos they received back were clearly the same person.

Meanwhile, the relationship with the Hernández brothers continued, according to Bandy. Tony gave López a paso fino horse, prized for their unique trot. Then, when López turned 36, he received a message that someone wanted to send him a gift and sent an employee to retrieve it. The employee returned with a $20,000 gold, Rolex “Presidential” watch from Juan Orlando. “He wanted to know where we were,” Bandy said, reflecting on the motive behind the gift.

The Capture

As the sun set on June 6, 2018 – two days after López turned 36 – he and Bandy were driving in a bulletproof Toyota Hilux pickup truck down a highway that leads to their Santa Barbara ranch when they came upon a checkpoint.

Acting on a tip, Honduran security officials had set up the checkpoint just for López and Bandy, ensnaring them as well as three of their workers that trailed behind in a Volkswagen Amarok pickup. But it was not the SIU, which had investigated the couple for years and usually conducts arrests of DEA targets. Rather, it was the military police, a controversial unit created by Hernández.

Upon being stopped, López attempted to bribe the soldiers, but they refused. The couple knew then that they were in real trouble. “[López] was crying before he got out of the car,” Bandy recalled. “‘They’re going to kill me,’ he said.”

More authorities arrived on the scene. They searched the detainees and then transferred them along with their vehicles to a nearby military base. On López, they found an ID card with his assumed name, Magdaleno Meza, more than $7,000 cash, and five Rolex watches. Bandy carried jewelry in her purse. They pretended like they hardly knew each other, and for a while, it looked like authorities might not find enough to hold them.

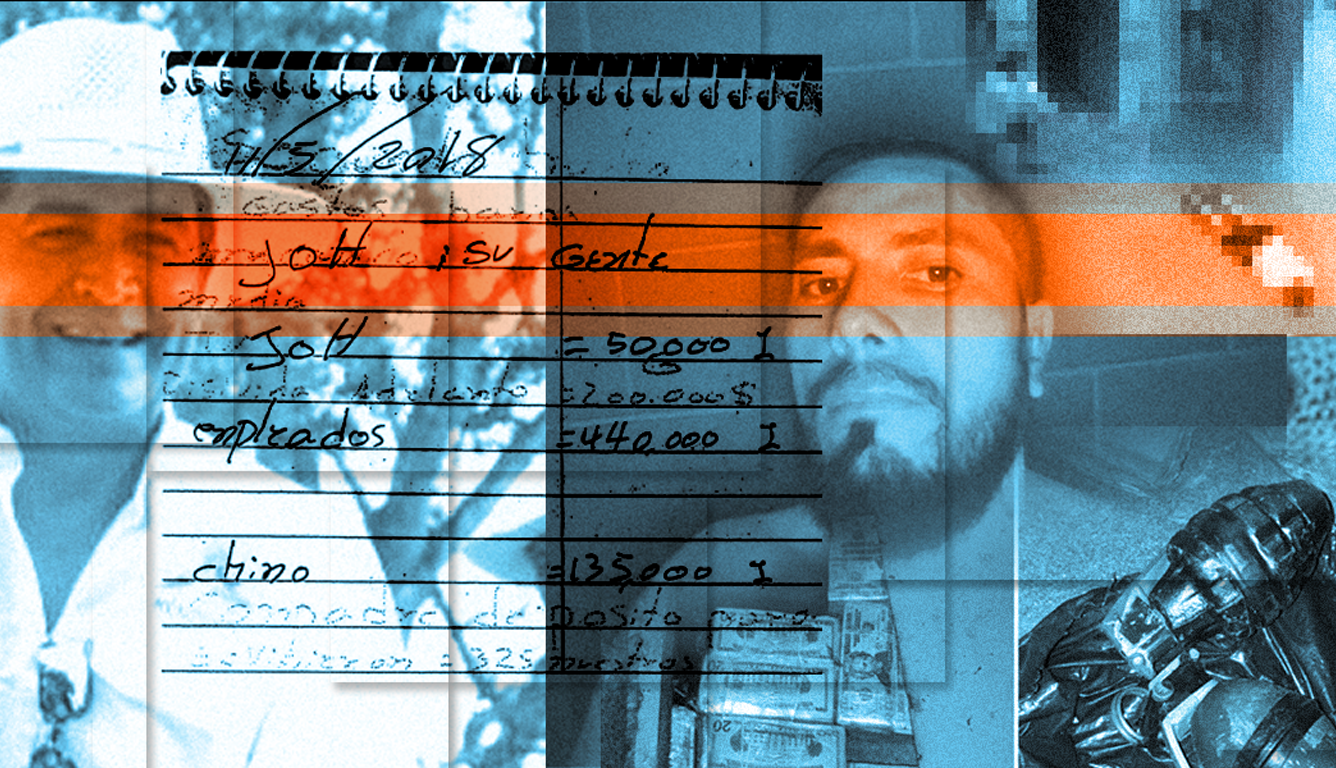

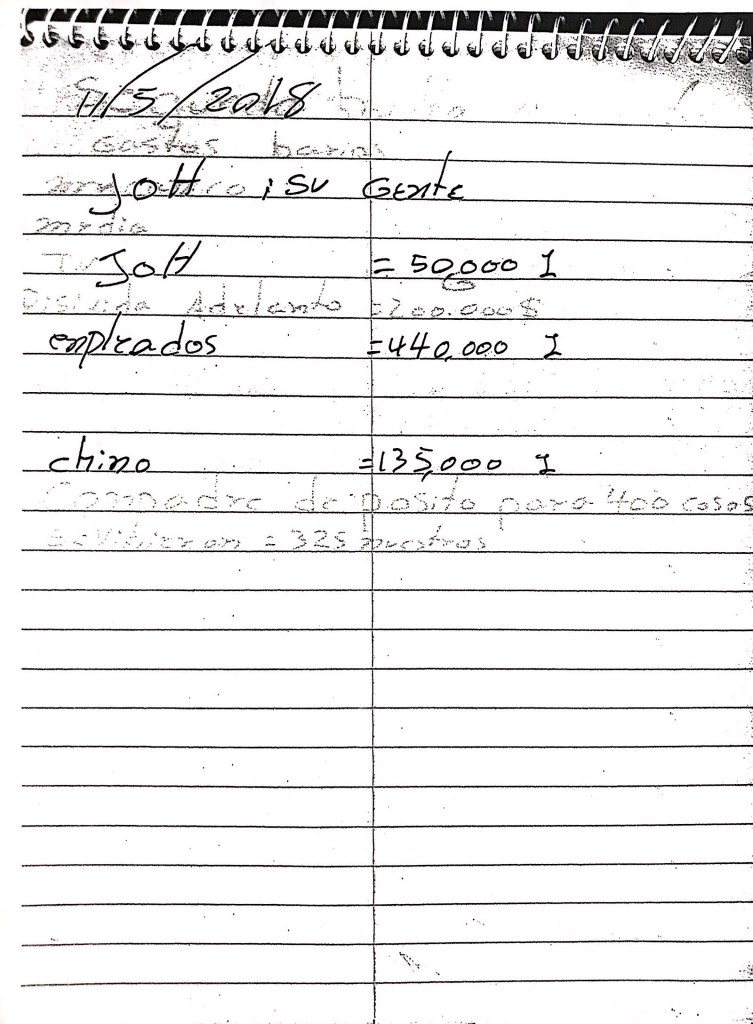

But then anti-narcotics agents cut open a hatch under the backseat of the Volkswagen, revealing nearly $200,000 in cash, grenades, and eleven ledgers. They discovered that a switch found in the Toyota connected to one found in the Volkswagen, and when connected together, a dashboard compartment popped open, exposing guns.

When the agents took the evidence to their office, they reviewed the ledgers and made an even bigger discovery. “At the time the Tony Hernández case was very well-known in Honduras, so upon the verification or the review of the ledgers, I found the name Tony Hernández,” one of the agents would later testify in court.

Another detail caught their eye. Several entries listed payments to an individual identified as JOH, the initials and alias of then-President Juan Orlando Hernández.

Bandy and López were booked into prison, the latter as Magdaleno Meza. When they had a hearing a week later during which the prosecution was expected to present evidence, the ledgers were conspicuously absent. Thirteen days passed between when the ledgers were reviewed and when they were registered into an evidence locker.

A lawyer for Tony Hernández used that gap in records to cast doubt on the veracity of the ledgers, suggesting that they might have been manipulated to implicate his client. Lawyers for Bandy and López, however, suggested that there was an attempted cover-up in favor of the Hernández brothers from within the Attorney General’s Office.

Pretrial

In November 2018, DEA agents arrested Tony Hernández on drug trafficking charges at Miami International Airport. There was no mention in the indictment of the drug ledgers or Tony’s links to Bandy and López. But a few weeks later, the Honduran Attorney General’s Office publicized the connection after seizing some of Tony’s assets, stating that there was evidence linking Tony to the couple’s arrest and that he had been interviewed in relation to the case.

US prosecutors made a passing reference to the Attorney General’s Office’s statement soon after, but did not make any further mention about the connection, or the drug ledgers, until the October 2019 trial. Meanwhile, people close to Juan Orlando and Tony worked to ensure that none of it could be used against them.

López received several visits on the brothers’ behalf in prison, first from another Hernández brother, Amilcar Hernández, a retired military officer. “Amilcar told him not to speak with anyone else,” Bandy told InSight Crime. “My husband said, ‘Ok, I’ll stay quiet, get me out of here.’”

But López grew suspicious as months went by and he remained stuck behind bars.

He hired a lawyer in the United States and attempted to negotiate with the DEA. The lawyer, Robert Feitel, visited López in jail. “We continued to try to further his case. Unfortunately, our client’s astonishingly brutal murder ended these efforts,” Feitel said.

In a voice message sent to one of his lawyers from prison, López made his intentions clear. “I am fully willing to be a collaborator of the American government, of American justice … I have a lot to offer … I’m at the service of, and with complete willingness, for whatever is necessary to be able to work with the DEA,” he said.

Then he received visits from a lawyer and a private investigator working for Tony’s defense. “A private investigator came right now on behalf of TH from the USA, on behalf of the lawyer that wanted me to tell him everything I knew about TH,” said Lopez in another voice message sent to one of his lawyers, referring to Tony Hernández by his initials. “I said to him, why am I going to tell you everything if it doesn’t benefit me at all?”

The lawyer also visited Bandy. “He said to me that he came on behalf of Amilcar, that he was a lawyer and a friend of Tony. He said that the president was sad for his brother and that his mother was suffering,” she recalled.

The lawyer attempted to pry information from Bandy, but she was not interested in talking about details, offering a warning instead. “I told him that my husband had told me everything. I know it all. If my husband doesn’t speak the truth, I will. If you kill Magdaleno, I have all the information,” she said.

Post Trial

At the last minute, US prosecutors brought the ledgers and one of the Honduran anti-narcotics agents who found them to New York for the trial of Tony Hernández. Prosecutors displayed for the jury an entry dated February 27, 2018 for an apparent shipment of 650 kilograms of cocaine sent by “Tony Hernandes.” The entry details expenses such as shipping costs, lost product, and a $1,000,000 deposit to “Toni.” It was the underworld version of an invoice.

On October 18, 2019, Tony Hernández was found guilty. His trial made clear that Juan Orlando could be the next target. The ledgers were one of the most damning pieces of evidence presented by the prosecution – and they implicated both brothers.

Although López wanted to cooperate with the DEA, he was trapped in prison in Honduras because US authorities had not sent a request for his extradition prior to his arrest. Even though he had been indicted by the United States two years before, he now had to serve out his legal process at home first. It was a loophole in the extradition treaty that could be exploited to keep traffickers in Honduras and prevent them from cooperating with US prosecutors.

Eight days after the verdict, López was standing in a hallway speaking with the prison warden when a masked guard opened a door to the side. Out popped members of the MS13 gang who fired upon López immediately, then mutilated his body as blood spilled across the floor. A video of the horrific act appeared on social media with uncanny speed.

The Interview

A couple of weeks after the murder of López, Bandy sat inside the women’s prison, her painted black fingernails rattling upon the table as cats and dogs crawled around and guards watched on from nearby. “It was completely shameless what they did!” she cried.

“[López] told me that the president of this country was going to kill him for his links with his brother, and we have the proof,” Bandy said.

Bandy said that the name Tony that appears in numerous entries in the drug ledgers corresponds to the former legislator, Tony Hernández, and that the initials JOH correspond to the former president, Juan Orlando Hernández. But the ledgers were not the only proof.

Soon after the interview, a lawyer for Bandy showed InSight Crime two photos. The first was a picture of Hernández outside a home that Bandy claimed was one of theirs. The second was a photo of an apparent kilogram of cocaine stamped with the initials TH.

During the trial of Tony Hernández, prosecutors presented a photo obtained through an intercept of an apparent kilogram of cocaine with the same TH stamp. Three witnesses testified that it was a stamp used by the former legislator in representation of his initials. Besides the picture presented at trial, the only similar one that exists in the public domain is from a seizure in Costa Rica in 2016.

InSight Crime made a contemporaneous comparison of the photo of the kilogram shown with the two public photos, noting that while the stamp was the same design, there were minor differences in the photo, such as the background and the wrapping, that indicated that it was a third, unique example.

The photo of the brick of cocaine, combined with the ledgers and the testimony of either López or Bandy, would have been damning for either Tony or Juan Orlando Hernández. But Bandy and others close to the couple said there was even more evidence, including more photos and more ledgers.

Partners in Crime

Throughout the interview, Bandy hid behind the stereotype of the innocent housewife. “Nery told me,” she would say. She knew things, but was merely a bystander. “I’m not a drug trafficker, I’m a victim in this situation,” she said. Still pending trial, any admission of her own guilt would have condemned her to a long prison sentence in Honduras.

InSight Crime spoke with a dozen people who were friends, associates, or otherwise had contact with Lopez and Bandy. While much of what sources knew about the couple supported the account she gave InSight Crime, including the details on the Hernández brothers, they differed on her involvement in trafficking.

“Erika was the brains, Nery was the arms,” said a lawyer.

While people who knew them described López as humble and calm, they described Bandy as a woman of contrasts, a doting mother who liked the finer things, but was also “volatile” and “bloodthirsty.” Workers called both “boss.”

Several sources suggested that Bandy was the one who had connections with drug traffickers. “I made Nery,” one recalled her saying. She might have proved more valuable to the DEA than her husband.

Life Outside

Within weeks of the interview, a lawyer who had worked for the couple was killed at a cafeteria. Then, the prison warden, Pedro Ildefonso Armas, who was speaking with López when he was shot, was murdered in a hit that had all the hallmarks of organized crime.

The killings had a chilling effect and Bandy went silent. She got out of prison in 2022 thanks to a reform to the penal code that upped the bar for money laundering charges. But she was hardly free. Each month she had to make an appearance at court as part of her probation and she was prohibited from leaving the country. Fear consumed her life and she was constantly changing phones and homes.

SEE ALSO: Landmark US Drug Trial Leaves Bloody Trail in Honduras

At different moments, people close to Bandy encouraged her to seek out a deal with US authorities to save her life, and in early 2023, the DEA tried to contact Bandy in an attempt to gain her cooperation, lawyers told InSight Crime. Had she agreed to testify against Hernández, it could have sealed the case for the prosecution.

Bandy made clear that the entries with the initials JOH correspond to drug money paid to Juan Orlando Hernández. Her photos and other documentation would have made powerful supporting evidence.

But she refused. “You don’t know the tentacles of these people,” Bandy told a lawyer, explaining her fear of retribution from the Hernández family. She worried about her children and there was no indictment to twist her arm, as in the case of her husband.

Bandy wanted to leave Honduras and was eagerly awaiting the end of probation so that she would be free to travel. But to do that she needed money, and since getting out of prison she had been collecting on old debts.

On June 22, 2023, Bandy parked at a bakery in a bulletproof Toyota Prado SUV, according to security camera footage. When her bodyguards pulled up in a truck, she got out and then suddenly rushed inside when another truck arrived, this one carrying heavily armed men wearing bulletproof police vests.

First, they secured the scene outside, forcing the bodyguards to their knees. Then they went into the bakery. Bandy, wearing a summer dress and sandals, rushed behind the counter. She held her hand out in front of her face as though to say, “Don’t shoot.”

Then they came behind the counter. They were not real police, but a sophisticated group of assassins in disguise. Bandy grabbed a bystander and attempted to use her as a human shield. A man gestured for her to move away from the woman. When Bandy refused, he fired over her shoulder, then, after she fell to the ground, a bullet to her head, then another two for good measure.

The next day, her lawyers received notice that her probation was over.