Leftist opposition candidate Xiomara Castro appears to have ridden a wave of outrage to become Honduras’ next president, beating out her right-wing rival in the ruling party, which has come under fire for its involvement in drug trafficking and corruption.

As the candidate for the Libre party, Castro is set to become Honduras’ first female president after receiving more than 960,000 votes, or around 54 percent, with a little more than half of all votes counted, according to data from the National Electoral Council (Consejo Nacional Electoral – CNE). Her historic victory marks the end of 12 years of National Party rule, which began in mid-2009 after then-President Manuel Zelaya, Castro’s husband, was removed from power in a military coup backed by business elites.

Her victory is a repudiation of the ruling party and outgoing President Juan Orlando Hernández – long a close ally of the United States – whose tenure has been marked by repeated accusations by US prosecutors that he protected drug traffickers, including his own brother, in exchange for bribes.

SEE ALSO: One Party, Many Crimes: The Case of Honduras’ National Party

Below, InSight Crime looks at what Castro’s win – amid massive citizen turnout – means for narco-politics, anti-corruption efforts and policing in Honduras.

An End to Narco-Politics?

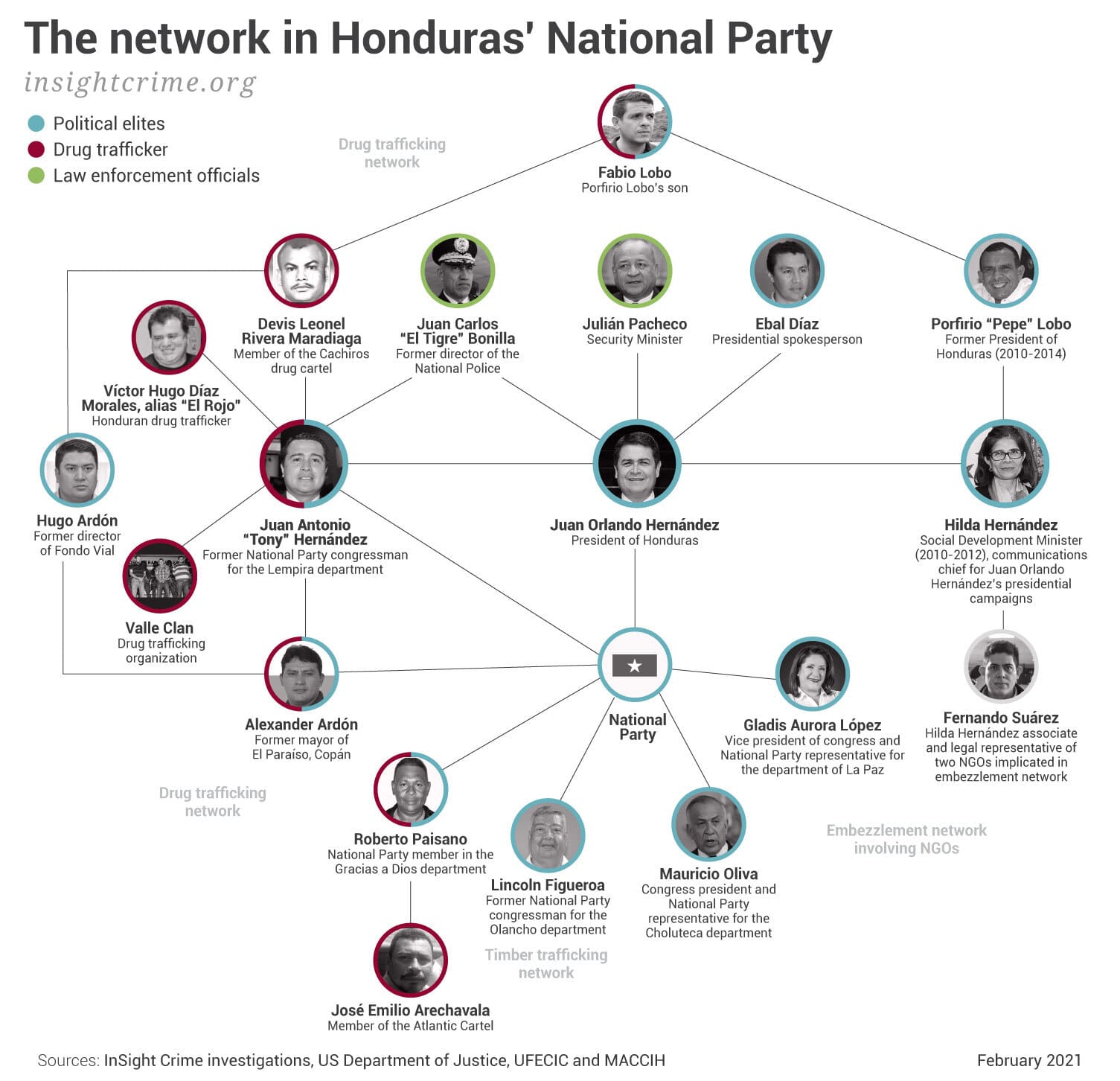

From local mayors up to president Hernández, the National Party’s tenure has been overshadowed by narco-political scandals, including allegations of systemic corruption and intimate ties between organized crime groups and political power at every level.

Former President Porfirio Lobo Sosa, who assumed the presidency after Zelaya’s ouster in 2009, allegedly accepted bribes from the infamous Cachiros drug clan. Lobo’s son, Fabio, was later convicted and sentenced to 24 years in US prison for trafficking cocaine alongside the Cachiros.

The most ignominious example of the National Party’s drug ties was the conviction and life sentence given to President Hernández’s brother, Tony, for using his political connections to traffic cocaine into the United States for the better part of a decade.

At the local level, Tony brokered deals with National Party officials, such as former El Paraíso mayor Amilcar Alexander Ardón Soriano, to secure funds and support for the party. In exchange, Ardón and the drug trafficking group he directed, known as the “AA Cartel,” received government protection and the appointment of allies to prominent posts. Roberto and Seth Paisano Wood, brothers and National Party operators, were also accused of trafficking drugs with the Atlantic Cartel along Honduras’ northeastern Caribbean coast.

President Hernández himself emerged as one of the main protagonists in Tony’s trial, with former traffickers describing million-dollar bribes to Tony for the president and official protection for cocaine labs.

US prosecutors have repeatedly named President Hernández in court filings, implicating him in a wide range of criminal activity, which he has consistently denied. Speculation has swirled over whether President Hernández could face charges upon leaving office early next year.

In her official plan, Castro acknowledged that drug trafficking groups have “captured” the Honduran state and its security forces, citing “multiple accusations” by Honduran and US prosecutors in which officials have been “identified as drug traffickers or accomplices of these structures.”

However, it remains to be seen if Castro will have the resources and support needed to dismantle the deeply embedded criminal structures that National Party officials and criminal groups built up over the last decade, often with the backing of corrupt security forces.

Restoration of Anti-Corruption Efforts

In her last rally in Tegucigalpa, Castro told supporters that a woman was needed to “manage funds with transparency and to say ‘out with the corruption’ in Honduras.”

It wasn’t hard for Castro to set herself apart from the National Party, which misused public funds, dismantled anti-graft efforts and instituted reforms that preserved widespread impunity.

One of the most egregious examples came amid the COVID-19 pandemic when the head of the government agency charged with procuring emergency medical supplies was accused of profiteering in the purchase of seven mobile hospitals for $47 million. Five of those hospitals never opened.

In her plan, Castro promised to restore an anti-corruption commission that was disbanded under Hernández’s watch. The end of the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (Misión de Apoyo Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad en Honduras – MACCIH) came in early 2020 when the Honduran government failed to reach an agreement with the Organization of American States (OAS) to renew its mandate.

Despite a number of obstacles, including financing and meddling by congress, the MACCIH had managed to take on high-profile cases, including that of former first lady Rosa Elena Bonilla de Lobo, the wife of former President Lobo. She was convicted on charges of fraud and embezzlement.

Its days, however, were clearly numbered when it came under withering attacks from political and economic elites, who claimed it had exceeded its powers. Some of those same elites, including legislators, were under investigation by the Attorney General’s Office with the help of the MACCIH.

Court decisions also appeared to favor the corrupt. For example, the conviction against the first lady was later overturned by Honduras’ Supreme Court. An appeals court ended the prosecution of public officials accused in the Pandora Case – a vast corruption scheme that saw millions in government funds embezzled for political purposes. A number of the officials came from the National Party, and sham non-profits used in the scheme were linked to the family of President Hernández, according to a Univision investigation.

Legislators, meanwhile, approved controversial amendments to the penal code that lowered sentences for corruption and drug trafficking cases and made it more difficult to prosecute money laundering investigations.

Maureen Meyer, the vice president for programs at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), said the Honduran population was frustrated by a number of issues related to corruption. These ncluded not only drug trafficking but government corruption, such as the embezzlement of public funds meant to assist with hurricane relief, COVID-19 response and anti-poverty efforts.

“There was a growing frustration at the level of corruption that country has experienced during the last decade,” she told InSight Crime.

Demilitarizing Public Security

When it comes to law enforcement, Castro’s top priority is not combating the country’s gangs but reining in militarized policing and iron fist security policies, which have largely failed to produce any substantial security gains.

This focus is a significant break from the ruling party and President Hernández, who came to power on the promise of putting a “soldier on every corner.” At that time, Honduras was one of the most violent countries in the world due in part to turf wars between its two largest street gangs, the MS13 and Barrio 18.

Hernández made good on his pledge, deploying several new military police units, including the Military Police of Public Order (Policía Militar de Orden Público – PMOP). Violence reduction came at a high price, as the force was also accused of human rights abuses, including cases of extrajudicial killings, torture and illegal detentions. Members of another US-trained elite police unit, known as the Tigres, were charged with stealing $1.3 million in drug money and accused of other misconduct.

In her security plan, Castro promised to foment community policing efforts, which will have a “more horizontal and trusting relationship with the population.”

As recently as last year, PMOP officers shot and beat three brothers selling bread, killing one and leaving the other in critical condition. The officers were enforcing pandemic lockdowns.

Meyer said Castro’s message was important to voters because “people need to feel safe at home and feel that the police can be part of the solution.”

Tellingly, Castro made no direct mention of street gangs in her plan. Veiled references to them came in a section about violence that included businesses having to pay impuestos de guerra (war taxes, a term for extortion payments) and schools being used for forced recruitment.

The gangs also were not a direct focus of her violence reduction efforts, which included providing better mental health services, ensuring people have work and providing secure environments for students.

Though the street gangs continue to plague the country, voters were less inclined to be swayed by the same law and order message when many were suffering themselves, Meyer said, particularly in the wake of economic devastation from the pandemic and hurricanes.

“We’ve seen poverty increase and a real sense of desperation by a growing part of the population,” Meyer said. “So while yes, they may be concerned with MS13 operating in their neighborhoods, they are also concerned with surviving.”