Since Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador took office in 2018, his morning press conferences have been known as a space where journalists can gauge the temperature of the administration more than obtain a truthful, verifiable account of what is actually happening in the country.

This is why it was surprising when Alejandro Svarch, head of the Federal Commission for Protection Against Health Risks (Comisión Federal para la Protección de Riesgos Sanitarios – Cofepris), took the stage at the conference on June 7, 2022, and gave a troubling speech about Mexico’s top health agency.

Cofepris is the state entity in charge of issuing import permits and the commercialization of chemical substances. It also watches over precursor and pre-precursor chemicals, which can be used to manufacture synthetic drugs, and monitors entities that have inventories of these substances. This makes Cofepris an essential actor in regulating the flow of precursor chemicals in Mexico.

Svarch did not appear to leave out key facts or try to shift the blame, as López Obrador and other officials have done when facing tough questions. Instead, Svarch stated that Cofepris had been an agency where “corruption went from top to bottom” for years.

“We found that, on the surface, [Cofepris] seemed to function smoothly, but deep down … there were corruption networks where interest groups held the health agency hostage,” he said.

Svarch would continue to offer up more details in the months ahead. In November 2022, he claimed that certain Cofepris officials had allowed the entry of various chemical substances without tracing them. These were reportedly later used for illicit purposes. He added that some agency officials would authorize permits and import applications “to whoever paid up.”

Officials essentially created an extortion scheme, which allowed drug traffickers to import large quantities of synthetic drugs like fentanyl, as well as the precursor and pre-precursor chemicals needed to synthesize such drugs, according to Svarch. Certain middlemen — which Svarch referred to as “coyotes” – even charged fees in exchange for guaranteeing a swift approval process for import permits.

Svarch seemed to be referring to a case that came to light in October 2021, when Health Minister Jorge Alcocer told reporters that Cofepris had to call in the Mexican Navy to assist with an investigation into the illegal importation of fentanyl.

In total, 32 Cofepris employees were fired. López Obrador confirmed during another morning conference in March 2023 that some of these had been linked to fentanyl trafficking, and that they had granted import licenses to ghost companies.

The Cofepris scandal is a classic example of the institutional corruption that has existed in Mexico for years, obstructing the implementation of regulations that appear strong on paper.

Mexico has an essentially impeccable legal framework for the regulation of precursor chemicals by international standards. But over the course of a year-long investigation, InSight Crime found that corruption and other problems make it far from effective in practice.

Mexico’s Robust Regulatory System

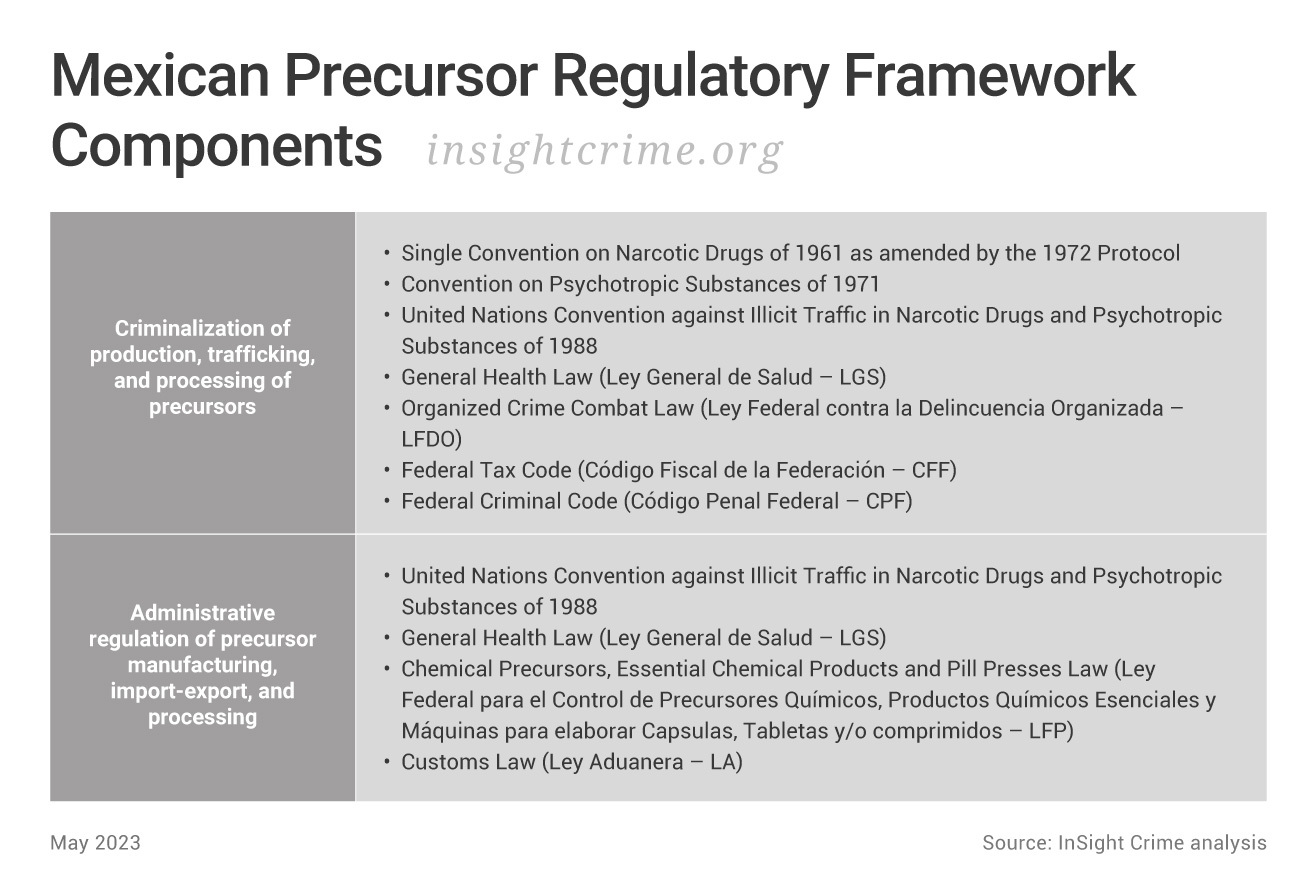

Mexico is part of several international cooperation agreements on drug trafficking and is a signatory to all United Nations (UN) conventions on the matter. It has also worked closely with the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) to standardize the control of precursor chemicals.

Mexico has one of the most complete lists of chemicals subject to monitoring, regulation, and control in the world, which almost entirely match their counterparts in the United States.

These are the lists of narcotics and psychotropic substances included in Mexico’s General Health Law (equivalent to the substances listed by the US Controlled Substances Act) and the Federal Law for the Control of Precursor Chemicals and Essential Chemicals (equivalent to the substances regulated by the US Chemical Diversion and Trafficking Act). In addition, the Mexican government has created the Dual-Use Susceptible Substances Watch List, which watches over unregulated substances that, although they may have legal uses, can be used to produce synthetic drugs.

Other laws and codes do not specifically criminalize precursors, focusing instead on their associated activities. These are the Federal Law against Organized Crime, the Federal Fiscal Code, and the Federal Criminal Code, which deal with the broader aspects of smuggling and its link to the production of illegal drugs.

Mexico’s health agencies are the primary regulators of chemicals. They are legally obligated to work with various ministries, including those for foreign affairs, finance, the economy, and communications and transportation, to enhance their visibility over the supply chain. All these institutions must also refer any suspected diversion of regulated chemical substances to the Attorney General’s Office (Fiscalía General de la República – FGR).

In addition, Mexican health authorities have increased their collaboration with the Ministry of the Navy (Secretaría de Marina – SEMAR) and the National Guard to detect and analyze chemical substances at ports and other entry points into the country.

This legal framework has been an essential step in addressing synthetic drug trafficking in Mexico. But these regulations are not sufficient, as law enforcement has been far from effective in practice.

Corruption At All Stages

Understanding why Mexico’s laws and regulations have not been properly implemented is a complex issue. Problems have stemmed from a lack of coordination between agencies, insufficient staff and training, and a lack of protection for whistleblowers.

But endemic corruption remains at the heart of the matter. Corruption schemes are common at the highest levels of the Mexican government, with senior law enforcement and security officials having assisted the country’s foremost criminal groups.

Examples of graft have been found at ports of entry and transit points, through which synthetic drugs and precursor chemicals travel, as well as in areas where clandestine laboratories operate.

SEE ALSO: 5 Takeaways From US Indictments of Chapitos, Associates

This was evident in the recent US indictment against the sons of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, alias “El Chapo,” known as the Chapitos. Prosecutors and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) claimed that networks dedicated to sourcing chemical precursors allegedly used bribes to ensure the substances would enter Mexico, to procure false labels for them, and to find intermediaries whose names can be used to create front companies.

During our fieldwork in the state of Michoacán, an epicenter for methamphetamine production, we found that several armed groups, including some involved in the synthetic drug trade, were protected by security forces in the areas where they operated. And one meth and fentanyl trafficker from the same state stated he would use bribes to ensure he could smoothly access essential chemicals.

Lack of Coordination

Poor collaboration between relevant government entities means that much of the precursor chemical supply chain goes unmonitored. Mexican government officials confirmed this to InSight Crime, stating that a lack of information-sharing between agencies further limited the scope of their work.

For example, one National Guard official, who asked to remain anonymous because he was not authorized to speak on the subject, stated the agency had no visibility over customs at Mexico City’s airport, at major entry points for precursor chemicals and fentanyl. Since February 2022, Mexico’s Navy has taken over responsibility for security at major customs points. While the National Guard is in charge of overseeing highways and certain other airports, there has been little exchange of information between the two bodies, leading to a significant information gap, the official explained.

“We don’t know what is coming in [to Mexico City airport], and we can’t coordinate efforts with our personnel in the city and at other customs points,” he said.

Similarly, Mexico has no standardized data about seizures of chemicals or other actions taken against the trafficking of precursor chemicals. Each agency involved collects its own statistics. In some cases, these reports do not specify the types of chemicals being seized or have only partial data.

In May 2020, for example, several media outlets reported that the Navy seized 169 kilos of fentanyl precursors in the port of Ensenada, Baja California. But such a seizure does not appear in official data shared by the Navy with InSight Crime.

The 2022 Mutual Evaluation Mechanism of the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD) noted that while Mexico has comprehensive national programs, “it has not established inter-institutional cooperation mechanisms between public and private institutions to provide a comprehensive response to illicit drug production.”

Little to No Prosecution

Although agencies must notify the FGR of possible diversions of chemical substances and similar legal violations, this system does not appear to be functioning. Information requests revealed that no related case has been referred to the FGR for possible prosecution in the last ten years.

The absence of any such cases is highly unlikely, given the number of seizures of precursor chemicals in Mexico, both at ports of entry and in lab raids. On the contrary, this may be a clear sign that, while Mexico’s reporting requirements are mostly in line with international best practicing, they are having little to no influence on actual legal action.

There is little incentive for any of the agencies involved to proactively report such diversions and criminal activity to the FGR. Doing so would see the officials or agencies involved in criminal proceedings which are costly and time-consuming.

In addition, while the number of precursors, pre-precursors, and essential chemicals being seized has remained steady, this has not led to more criminal investigations.

InSight Crime asked the Attorney General’s Office for statistics on investigations related to the diversion of chemicals for illicit use. The agency responded that this was confidential, as they could only share information on closed cases. However, this was not shared either.

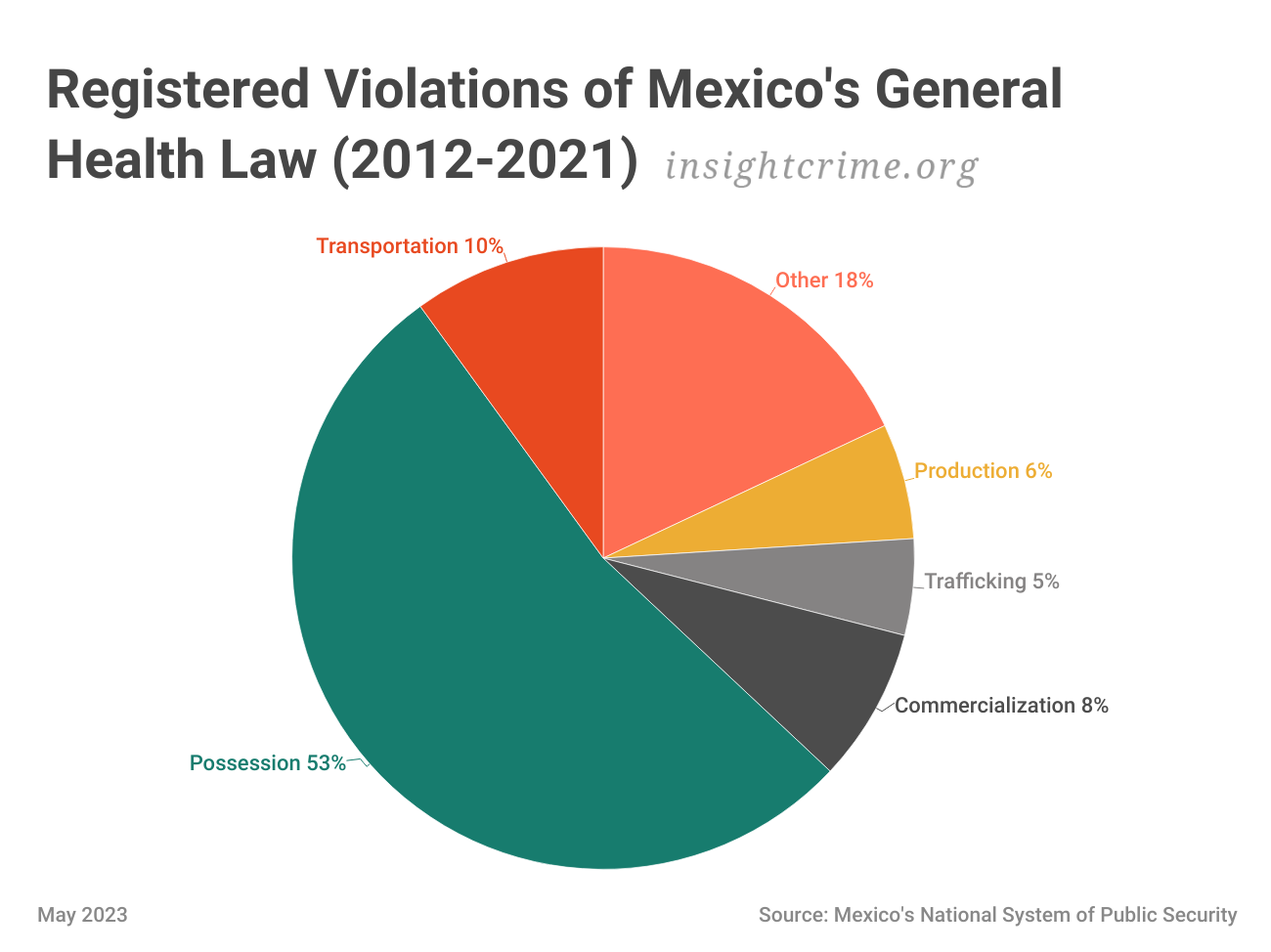

And while there have been a significant number of investigations related to infractions of the General Health Law, more than half are related to the possession of specific substances and only 6% to drug production.

Other cases related to precursor chemical trafficking have been few and far between and also do not correspond to the increase in seizures. The Ministry of the Navy, for example, told InSight Crime that, from December 2021 to December 2022, it only shut down eight companies related to the diversion of chemicals. Prior to this, while information had been released publicly about companies being investigated for their involvement, there had been no confirmation of their prosecution.

One of the best-known cases was that of Escomexa and Corporativo y Enlace Ram, two companies based in the city of Guadalajara and registered at residential addresses. Both have been linked since at least 2020 to the importation of fentanyl and its precursors. According to information shared by the FGR, investigations continue to this day.

*Steven Dudley and Jaime López-Aranda contributed to this report