Bolivia is in the midst of a gold rush caused by record gold prices and growing international demand. This gold rush has been facilitated by permissive mining regulations that blur the line between legal and illegal.

The spread of mining throughout the country and the broader Amazon in the last few years has left deep environmental scars. Mining has become one of the main drivers of deforestation and is threatening protected areas and native communities.

Unlike other Amazon countries, such as Peru and Colombia, the main mining players in Bolivia are mining cooperatives. Their economic and political power, and the loosely regulated national industry they operate in, have emboldened them to expand their mining operations to the most remote corners of Bolivia’s Amazon, including protected areas. But their operations are too often associated with flagrantly illegal acts, as they operate without environmental license or in alliance with dubious Chinese and Colombian companies.

*This article is part of a joint investigation by InSight Crime and the Igarapé Institute on illegal mining, wildlife, timber, and drug trafficking in the Bolivian Amazon. Read the other chapters here, or download the full PDF.

Prospectors are tearing up Bolivia’s Tuichi River in search of gold. The waterway descends into Madidi National Park, a natural wonder, home to more than 1,000 species of birds and some 200 species of mammals.

As the miners have grown more brazen in breaching the reserve, patrols by park rangers have been cut back, said Marcos Uzquiano, Madidi’s former director. When rangers do head out, they reduce their inspections to merely noting illegal activity, such as cylinders of diesel fuel being carried in. But lately, they fear doing even this, after having received threats. In certain sections of the park, the miners “decide who enters,” Uzquiano said.

“We have reached a point where all authority has been lost,” said Uzquiano, who was transferred from his post after speaking out about the situation.

Using heavy machinery that includes backhoes, dump trucks, and front-end loaders, the miners level embankments and dig pits. Mounds of rubble are left behind, and the once-clear river has become choked with silt, Uzquiano said.

“All the mining waste is being dumped directly into the river without any mitigation measures,” he said. The waste, also known as tailings, includes toxic mercury used in the separation of gold. “It’s completely out of control,” Uzquiano said.

Bolivia’s government, though, has not stopped the plunder, despite having established the reserve in 1995 to form one of the world’s most biologically diverse protected areas. Rather, it has encouraged gold mining, handing out concessions within the reserve, which runs along Bolivia’s upper Amazon River Basin.

SEE ALSO: Beneath The Surface of Illegal Gold Mining in the Amazon

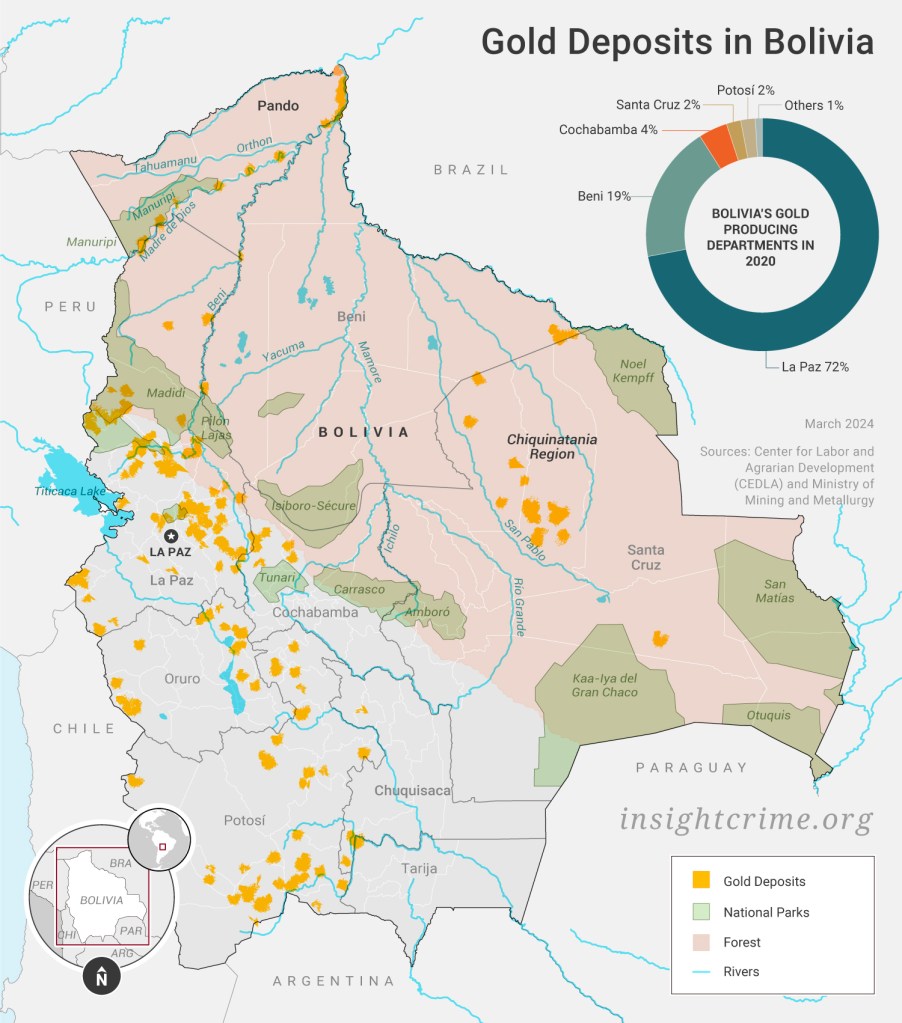

Bolivia is in the grips of a gold boom, stoked by soaring prices. Eight of Bolivia’s nine departments produce gold. Gold production came from 6.3 tons in 2010 to 42 tons, worth about $1.7 billion, in 2019. Between 2010 and 2021, Bolivia exported 240 tons of gold. The previous decade, it exported just 70 tons. The open secret is that Bolivia’s gold rush is fueled by its having virtually no controls on the mining, sale, or export of the precious metal. “There is no monitoring, from the operator at the site all the way to commercialization,” said Alfredo Zaconeta, a mining researcher at the Center for Labor and Agrarian Development (CEDLA).

Digging Into Gold Mining Cooperatives

Nearly all of Bolivia’s gold is produced by small-scale mining cooperatives, known locally as cooperativas. These sometimes act like mafias. Politically powerful, the cooperatives have been known to hold the government hostage, to corrupt and coerce mining agency officials, and to have shady dealings with Colombian and Chinese mining outfits. These miners enter protected areas and employ destructive techniques, including using wildcat equipment such as excavators, massive dredges, and poisonous mercury. They operate in a near state of impunity, thanks to gray areas in Bolivian law and little oversight by the government’s mining agency, the Jurisdictional Mining Administrative Authority (AJAM).

“There is a level of flexibility and exceptions (…) that give the cooperative mining sector the possibility to really behave like an illegal miner,” said Oscar Campanini, who has investigated mining as director of the Documentation and Information Center Bolivia (CEDIB), a non-profit organization that reports on social issues.

Though they existed even earlier, mining cooperatives emerged in the 1980s after the dissolution of Bolivia’s state-owned mining company, Comibol. Made up of unemployed miners, the cooperatives were provided mining concessions in abandoned shafts or on pieces of land for little money.

A boom in mineral prices beginning in the 1990s caused Bolivia’s mining cooperatives to surge in number. In recent years, gold cooperatives have led the charge. In 2010, there were 459 registered gold cooperatives in the La Paz department. By 2019, that number more than doubled to 1,230.

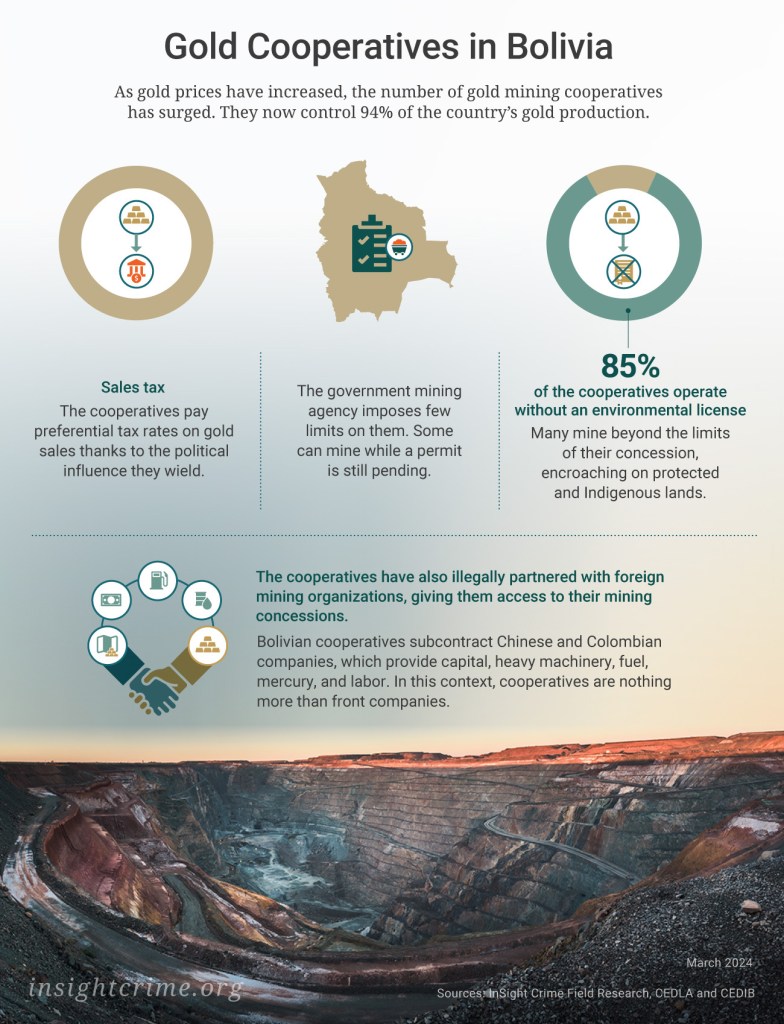

According to CEDLA researcher Zaconeta, the cooperative sector controls 94% of the country’s national gold production. The remaining percentage is in the hands of the private and state sectors. Unlike in neighboring Peru, there are few big foreign-owned mining firms.

The cooperatives are supposed to be collaborative ventures in which each member is a socio, or partner. The reality is that they are often owned or controlled by families or small groups. Many of their individual members remain poor, while cooperative leaders consolidate power and wealth.

On a national scale, the mining cooperatives are organized under larger federations. Most of them operate in La Paz department, but also in Bolivia’s Amazon region. These include the North La Paz Mining Cooperative Federation (FECOMAN), the Regional Mining Cooperative Federation (FERRECO), and the Bolivian National Mining Cooperative Federation (FECOMIN). A 2014 paper on the cooperatives described FECOMIN as cloaking itself in “discourses about ideological alliances and mutual support, while it blackmails and coerces the government.”

The cooperatives supported former President Evo Morales (2006-2019) when he came to power. They backed Morales during much of his tenure, and he rewarded them with political posts. But they also bent him to their will – often through massive demonstrations – whenever the government dared to defy their interests, like increasing taxes or limiting mining concessions. In 2016, protesting mine workers kidnapped and beat to death Bolivia’s deputy interior minister, Rodolfo Illanes, amid an escalating conflict over mining legislation.

The government pursued those responsible for the murder of Illanes, but there was no strong implication for the cooperative sector. In fact, today, the cooperatives continue to play an important role in the government and in the ruling party, Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), while also maintaining the ability to mobilize members to further their interests.

“They evidently have a political presence that has allowed them throughout these 15 years to direct and define part of the actions, legal norms and policies on the issue of mining,” Zaconeta said.

One measure of cooperatives’ political power can be seen in the excessively low royalties on gold. Bolivia’s government levied just a 2.5% royalty on the gold they mine. Even that amount was not always paid, Zaconeta said. Figures from 2021 indicate that royalties on gold came to just 2.2% that year, according to Zaconeta. After a tense negotiation in October 2022, the mining cooperatives and the government agreed to pay another special tax of 4.8% on the gross sale of gold. By March 2024, this initiative has not been approved, but if approved, the cooperatives would have to pay 2.5% in royalties and the additional 4.8% in special taxes.

What’s more, the legal framework around mining, established by Law 535 in 2014, makes the cooperatives almost unaccountable. Cooperatives need merely to have requested registration as a legal entity to receive a mining title, or Administrative Mining Contract (CAM). Certain cooperatives established prior to 2014 can continue to mine, including in protected areas, while a request for a contract is in progress.

Bolivia’s mining agency, AJAM, is willfully ignorant at best – and at worst complicit – in giving free rein to the cooperatives. Mining concessions have been granted within protected areas in the Amazon. Little to no inspection is done to ensure that cooperatives constrain extraction to 25-hectare concessions. And some 85% of cooperatives operate without any environmental licenses at all.

Foreign nationals often underwrite mining operations. A Bolivian cooperative receives the mining contract, while heavy machinery and workforce are paid for by outsiders, who take up to 80% of the profits. Such dealings violate both the country’s constitution and mining laws, Zaconeta said. Mining cooperatives often merely act as fronts for foreign operators.

Rafts and Backhoes Plunder Amazonian Rivers

Dredging rafts operating in Bolivia’s Amazon waterways openly vacuum up mud to capture gold particles. These barges, mostly managed by Chinese and Colombian miners, can span two or three stories in height and are equipped with enormous pumps and high-pressure hoses to dredge the riverbed. Concurrently, backhoes are used to excavate riverbanks for additional gold.

These illegal rafts have infiltrated the extensive Beni River and its tributaries in the lowland Amazon region, including the Challana, Tipuani, Mapiri, and Kaka rivers.

Jimena Mercado was among the first Bolivian journalists to report on the presence of the dredges in the Amazon region. She said they had already begun “to besiege” Madidi in 2018 when she traveled to the region.

Officials in nearby towns were alarmed, Mercado said. In her book, “Tras el Dorado. Crónicas de la explotación del oro en la Amazonía” (After El Dorado. Chronicles of Gold Exploitation in the Amazon), Mercado described that she spoke with Edwin Peñaranda, a former council member for the riverside town of Teoponte. Peñaranda had become so concerned about the influx of Chinese illegal miners damaging the waterways that he corresponded with the AJAM to find out whether it had contracts with any Chinese miners.

The AJAM did not, but the cooperatives did. Mercado saw contracts between what she described as Chinese individuals and a wealthy cooperative owner with three dredges docked in Mayaya, just upriver from Teoponte.

Although foreign companies are prohibited from participating in the mining sector in Bolivia, Chinese and Colombians miners partnered with cooperatives that already have mining plots legally assigned to them to extract gold, said Zaconeta. They subcontract the mining operations, providing equipment, fuel, and mercury. They also hire laborers, which cooperatives – by their very nature – should not need.

SEE ALSO: A Toxic Trade: Illegal Mining in Amazon Tri-Border Regions

Some Chinese and Colombian companies have created “armed militias” to protect their operations, Mercado said. Shooters control some 50 mining plots around the village of Arcopongo, in central La Paz, she said.

The gold rush has also brought human trafficking to the Bolivian Amazon. In the towns of Mapiri, Guanay, and Ixiamas, bus terminal walls are plastered with photographs of missing women and girls. Some are lured to these mining towns with false promises of work as cooks, waitresses, or nannies.

Others are kidnapped, said Mercado, who recently spoke with a girl who was 8 years old when she was taken. She was among a group of 40 girls who were being sexually exploited in Mapiri, Mercado said.

Exporters Whisk Away Gold

Bolivia has long seen its mineral riches removed to foreign lands. During the Sixteenth Century, silver mined in Bolivia bankrolled the Spanish crown and made its way into the jewelry of Arab kings and the treasures of Ming dynasty emperors.

Gold is still exported today, but amounts have fluctuated wildly in recent years, jumping from 8 tons in 2013 to 36 tons the following year. Although it is not known how much gold is of illegal origin, “the drastic oscillations tell you something is wrong,” said Zaconeta.

Exports have also exceeded national production. In 2012, Bolivia exported some 27 tons of gold, about 15 more tons than it officially mined. Similarly, an extra 10 tons were exported in 2014. Zaconeta said the inflated gold exports suggest that illegally sourced gold, likely from Peru’s Amazon, is being laundered in Bolivia.

Gold extracted by numerous rafts along the Brazilian Madeira River, which connects the state of Rondônia with Beni, is also laundered, and traded in Bolivia, according to an investigation by Peruvian news outlet Ojo Público.

Gold passes through various hands, and sources are mixed prior to export, providing many opportunities for laundering. Individuals, including cooperative members, sell to gold shops that have sprung up around mining sites. A single miner can legally sell up to 2 kilograms per month, fetching up to $62,000. Buyers need only see an identity card.

Export companies purchase gold from these buyers, as well as from cooperatives. Approximately two dozen export companies are registered with the government. The law requires that these companies submit affidavits to Bolivia’s National Minerals and Metals Industry Registration and Control Service (Senarecom), documenting the provenance of the gold being exported and payment of taxes.

The source of the gold, in theory, is identified through mining identification numbers, which gold prospectors and sellers must obtain in order to operate legally. But the mining numbers and gold sources are self-declared at the time of sale, and Senarecom has no effective way to track the information provided.

The lack of oversight permits both gold buyers and exporters to falsely document titles, entities, and gold sources. This allows for the free movement of gold among cooperatives. Regulated as small-scale operations, most gold cooperatives are restricted to selling 20 kilograms per month. To get around this, a cooperative extracting more gold will transfer it to another – in effect laundering it.

For example, an estimated 31 tons of gold were produced in 2018 in all of Bolivia. About half was supposedly mined in the Beni department, despite having only 20 cooperatives registered there, according to Zaconeta. Gold is also sourced to fake cooperatives and mining numbers.

“There is no follow up,” Zaconeta said of Senarecom’s inspection activities. “The only thing the state does is to hold on to the declarations made by the operators.”

Unscrupulous international buyers contribute to the problem. Since 2017, buyers in India and the United Arab Emirates have accounted for more than three-quarters of Bolivia’s gold sales. This was an abrupt shift from 2016, when US companies bought more than half of the country’s gold. The switch came shortly after US metal dealers were scrutinized for buying gold of suspect origin exported from Bolivia as metal waste. It also came after a broad crackdown by US prosecutors on imports of gold mined illegally.

Exporters have since turned to buyers in India and Dubai, who pay quickly and ask few questions, according to experts. Exporters themselves have been caught taking gold out of the country illegally. In December 2020, at the El Alto airport in La Paz, authorities seized 331 kilograms of gold, worth $18 million, en route to Dubai.

The exporter, Goldshine SRL, allegedly falsified documents to avoid taxes. After the seizure, prosecutors opened an investigation against the company’s owner, Amit Dixit, on charges of illegally buying and selling mineral resources and making false declarations.

Despite the cloud of suspicion around Dixit, Bolivian prosecutors ordered the confiscated gold returned to him the following year. They also shelved the case. In March 2022, the senate held a hearing during which the head of Bolivia’s mining agency told legislators Dixit had fled the country, taking the gold with him. While under investigation, Dixit also managed to export another 278 kilograms of gold, officials revealed.

Bolivia has asked INTERPOL to put out an alert for Dixit’s arrest, but nothing has come from it so far. Opposition Senator Cecilia Requena called the investigation a disaster. “We all have lost,” she said. “The corrupt have won.”

Madidi: A Paradise Lost?

In 2000, National Geographic magazine celebrated the creation of Madidi, which it called Bolivia’s “spectacular new national park,” with a cover image of two red macaws in flight. Now the reserve serves as a grim illustration of the destructive power of Bolivia’s gold miners.

According to Madidi’s management plans, the area where resource extraction is permitted in the park increased nearly 65% from 2006 to 2014. Marcos Uzquiano, Bolivia’s park ranger, said he recalled some 53 mining concessions within the park in 2013. In 2021, when “we revised the grids again,” there were “100 concessions” inside the park. “That has been increasing year after year,” Uzquiano said.

Late last year, Bolivia’s mining agencies and the cooperative federations hatched their latest agreement, allowing for the increase in mining rights in Madidi and two other reserves, Cotapata and Apolobamba.

When the backdoor deal became known, a group representing Indigenous rights had people from across ten Indigenous territories march to and take over the offices of Madidi and the Pilón Lajas Biosphere. The outrage caused the government to quickly annul the agreement, in October 2022.

Such rare victories matter little when there is no one to guard Madidi from miners illegally entering its protected areas. “The park rangers in Madidi at the moment are completely alone,” Uzquiano said.