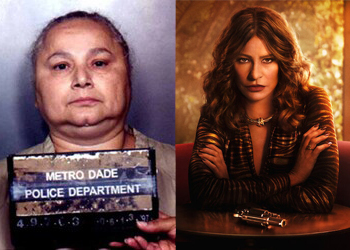

Netflix recently released its eponymous Griselda Blanco biopic, starring Sofía Vergara, which follows the drug trafficker’s journey from Medellín to becoming “The Godmother” of Miami’s drug empire. But like many other narco TV shows, it falls into the stereotype trap.

Griselda Blanco was one of the most prolific Colombian drug traffickers of the 1970s and ‘80s, and the most famous woman drug trafficker in Latin America.

SEE ALSO: Griselda Blanca, alias ‘La Madrina’

Blanco grew up in Medellín, and later moved to New York, where she began her drug trafficking career in the early 1970s. Together with her then-husband Alberto Bravo and his brother Carlos, she imported cocaine and marijuana to the United States. In 1974, Blanco was indicted and added to the state’s most wanted list. She and her husband fled the country, settling down in Medellín, Colombia, to keep running their illicit business.

By 1975, she had allegedly killed her husband and moved to Miami, where she continued her drug trafficking operations and became the head of a powerful drug trafficking ring.

Blanco successfully ran her operation until 1985, when she was arrested during a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) operation. After one of her hitmen testified against her, she was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Blanco was released in 2004 and moved back to Colombia, where she lived until 2012, when she was shot by a hitman in the streets of her neighborhood.

The show, by the producers and writers of Narcos and Narcos Mexico, picks up Blanco’s story in 1975. “Griselda” follows the trend set by its predecessors of presenting fictionalized versions of the lives of infamous Latin American drug traffickers, though very few of these have focused on women. The show has been marketed as a new take on the narco TV show in an attempt to set it apart from other adaptations like La Reina del Sur, an adaptation of the novel by Arturo Pérez Reverte, said to be loosely based on Sandra Ávila Beltrán.

InSight Crime Analysis

The fictionalized version of Blanco’s story presented by Netflix is advertised as a groundbreaking narrative about a woman who makes it in the male-dominated world of drug trafficking, but it ends up reproducing common stereotypes about women involved in organized crime.

The series attempts to portray Blanco as a mother who had no other choice than to get into the drug trade to provide for her sons after running away to Miami to escape her husband.

SEE ALSO: Female Criminal Leadership and Differing Use of Violence

Women’s involvement in the violent world of organized crime, especially in leadership roles, makes audiences — and society — uncomfortable. As a result, the show tries to turn her ascent into a drug queen into a melodramatic story of a mother going to extreme lengths to provide for her children, engaging in violence only to protect herself and her family. In contrast, in stories featuring male drug traffickers, violence is almost expected, and such justification is often absent, like in depictions of the Medellín Cartel leader, Pablo Escobar, in Narcos.

“The motherhood aspect seems to be necessary in order to anchor this violent character in femininity so that we can sort of accept the violence,” María Luisa Ruiz, a professor at Saint Mary’s College of California who has studied representations of women in the world of the drug trade, told InSight Crime. “There’s always this need to associate these ultra-violent heads of organized crime to their domestic life, which I don’t see in the portrayal of men.”

In reality, Blanco became a well-known figure for her use of violence. She was known to be ruthless with her enemies, and even pioneered the modus operandi of sicariato, or assassins-for-hire, which has become common in every country in Latin America.

The use of violence by female criminal leaders, which is varied and complex, is regularly overlooked by researchers, security forces, and prosecutors. Violent women, especially those associated with organized crime, are treated as outliers because they defy the gender stereotype of women as natural caregivers rather than perpetrators of violence.

“There’s something about that violation of social norms or expected cultural norms that I think people are still uncomfortable with,” said Ruiz.

Despite Vergara’s claims that she wanted to avoid glamorizing Blanco’s life, the show does the opposite, presenting her life as an (anti)hero’s journey of rise and downfall.

“This story is ‘Scarface,’ it’s ‘The Godfather’ with drugs,” said Ruiz. “It’s still that idea of one person having their journey… And to me, that focus on the individual really loses the fact that you do have this organized [criminal] network.”

Women involved in drug trafficking are not usually leading drug empires. They are more frequently employed in the lowest ranks of criminal groups, as human couriers, lookouts, and retail vendors, and few of them manage to climb the ranks of the male-dominated organizations. Despite their lower rank, women are frequently punished with harsher sentences than their male counterparts for the same crimes because they have betrayed the traditional ideas of femininity. The reality of women in prison, and their relationship with the criminal underworld, is less glamorous than the rise and fall of a drug queenpin, but just as illustrative of criminal dynamics.

The show also willfully ignores the true start of Blanco’s drug trafficking career, as several reviews have pointed out. By 1975, when the show begins, Blanco was already a prolific drug trafficker, managing a lucrative business with her husband. However, the show minimizes her role in his business to make her supposed ascent into a crime queenpin more dramatic. She is portrayed as a secondary character in her husband’s drug business, and at one point it is insinuated that he sexually exploited her to pay back debts to his brother.

However, court documents and journalistic investigations into her life show she was a central player in the trafficking scheme. This is another common error in narco TV shows: Despite being key players in illicit activities, women are often portrayed as secondary characters. Throughout the six episodes of “Griselda,” women, including Blanco herself, are referenced as sex objects and trophy wives who display little agency in their lives and are swept along by the men who run the drug business.

In the end, “Griselda” is just another narco TV show aimed at entertaining English-speaking audiences, rather than telling the true story of a hyper-violent woman that rose through the ranks of the drug world, and set a precedent for how we understand women’s participation in organized crime.