Why Bolivia is Burning

Behind the wildfires in the Bolivian Amazon

In 2019, a series of wildfires — largely set to clear land for agribusiness and make way for new residents — devastated Santa Cruz, the Bolivian state on the edge of the Amazon. Behind the fires was a pernicious force: organized crime. Illegal land grabs and timber traffickers spurred the wildfires, which continue today. In this podcast, through the stories of two volunteer firefighters, InSight Crime will tell the story of these fires and the criminals behind them, some of whom come from the government itself.

*This podcast is in English, but you can review the transcript and related content in Spanish here.

Transcript*

Steven: [00:00:02] This story starts with a fire. Actually, it starts with a lot of fires. The year was 2019. Bolivia had had plenty of forest fires before, but 2019 was special. Dozens of fires spread up and down the edge of the Amazon rainforest.

Newscast 1: [00:00:25] Incendios en la Amazonia parecen no tener fin. Sólo en la selva boliviana se han quemado más de 1 millón de hectáreas y los equipos de extinción trabajan en condiciones casi al límite para intentar controlar los fuegos.

Steven: [00:00:37] It was all over the news.

Newscast 2: [00:00:40] Bolivia is experiencing its worst fires in living memory.

Newscast 3: [00:00:44] Mais de 500 mil hectáreas foram destruídos nos últimos días por incêndios na Bolívia.

Newscast 4: [00:00:50] De l’autre côté de la frontière, en Bolivie, d’importants feux de forêt font également rage depuis trois semaines dans la zone de la Chiquitania située à l’est du pays.

Steven: [00:01:00] In the forests of Chiquitania, which is a region in the department of Santa Cruz, the fires turned into runaway blazes. According to the government, between July and October of that year, more than 3.5 million hectares were burned. This is an area about five times the size of New York City. But if you weren’t in Bolivia, you probably didn’t hear about it because it was the same year Brazil’s Amazon was burning in record amounts.

Newscast 5: [00:01:29] Fires are raging across Brazil’s Amazon Rainforest. There were roughly 20,000 fires there last month…

Steven: [00:01:36] Bolivia, like most countries, relies on volunteers to fight fires. People like Julio Zebers.

Julio: [00:01:43] … Conocemos que el 98% de los fuegos son por intervención antrópico, es decir, por el ser humano.

Steven: [00:01:51] Y Julio is a full-time activist, and he’s a part-time firefighter, although sometimes it feels a little bit like the other way around. If he sounds exasperated, it’s because he is. Ninety-eight percent of the fires, he says, are man-made.

Julio: [00:02:06] Pero de esos 98% que son intencionales en la Chiquitanía, ya prácticamente son todos. La mayoría son intencionales. No se sabe de accidentales.

Steven: [00:02:14] And in the area where he works, the Chiquitania forest in the state of Santa Cruz, all of the fires are man-made. The story of the fires and the organized crime that sparks them was part of an InSight crime investigation in the Amazon Basin. On this day, Julio was showing our investigators around an area that had recently burned to the ground.

Julio: [00:02:35] Esto fue justamente hace un mes y medio. Pasó el fuego… porque el fuego no te va a esperar. Él avanza en el día unos 7 u 8 kilómetros dependiendo del viento…

Steven: [00:02:43] Depending on wind conditions, fires can travel up to eight kilometers in one day, he says. As he speaks, he points to the damage which stretches about as far as the eye can see. This could have happened in one day, he adds.

Julio: [00:02:58] Entonces esto pudo haber pasado en un día. Desde allá de donde entramos, desde donde se empezó a ver el bosque.

Steven: [00:03:03] This is not your typical crime story. But it does reach all the way to the top of the political ladder in Bolivia. It’s also a story about migration and economic development, and how organized crime takes advantage of both. Ultimately, it’s about how organized crime accelerates the destruction of our environment and the people fighting to save that environment. That’s where Julio and other extraordinary volunteers, including a courageous housewife, come into the story.

Welcome to InSight Crime’s Podcast. I’m your host, Steven Dudley.

From street gangs in Central America to guerrilla and paramilitary groups in Colombia to prison gangs in Brazil, I’ve been investigating organized crime in the Americas for about 30 years. I’ve also been directing InSight Crime for close to 15 of those years, during which we’ve sent investigators to over 30 countries in the region to investigate criminal organizations.

This podcast will explore some of the most compelling stories we’ve found while we’re in the field. Sometimes we’ll talk to victims of crime. Other times we’re going to talk to crime fighters and other times to the criminals themselves. These are complex stories, and in this podcast, we will give you the human side that is too often overlooked while explaining the organized crime side that’s at the heart of the problem.

In this episode, with the help of two of our investigators and people like Julio, we’re going to explore why Bolivia is burning.

Mafe: [00:04:42] We were there because we were investigating environmental crimes in the Bolivian Amazon, but also in the outer edge of the Amazon jungle.

Steven: [00:04:51] That’s María Fernanda Ramírez, Project Manager at InSight Crime. We call her Mafe for short. She was traveling with Juan Diego Cárdenas, another InSight Crime investigator. We call him Juandi for short. They were talking to me after their trip to Bolivia where they were investigating illegal mining, illegal logging and land theft schemes.

Mafe: [00:05:11] So we met a whole host of people: environmental activists, government officials, park rangers. But, you know, one person that really stood out for me was Julio Zebers.

Steven: [00:05:26] That’s the same Julio I was talking about in the introduction. They told me he’s in his early 40s. That he was a tall guy. He was a bit skinny, strong. But he was also a chain smoker.

Mafe: [00:05:39] We asked him, why do you smoke so much? And he told us this story, that it was to keep away the lameojos.

Steven: [00:05:47] Lameojos. That’s a crazy type of gnat that heads straight for your face, and as Mafe told me, licks your eyes. Julio hoped his smoke would keep them at bay because when Mafe and Juandi met with him, the lameojos were dying of thirst. That’s because Julio had taken them to the site of the latest fire in the area. It had happened in the eastern part of the country, the lowlands, the so-called Santa Cruz and Grand Chiquitania region. It’s a remote place. It’s near, for example, where Bolivian authorities, with the help of the CIA, caught up with the legendary revolutionary Che Guevara and killed him. But it still has lush tropical areas which are fertile and ripe with a huge variety of trees.

Mafe: [00:06:33] But by the time we got there, we only saw destruction. The fire painted the trees and the ground a dark gray color that only fire can create. And several trunks, the bigger ones at least, had been cut down, except for one single tree. It was an almendro, a hard and resistant wood used in local markets for the manufacture of furniture.

Steven: [00:07:02] As they walked through the embers of the fire, Juandi asked Julio who, or what, was responsible for this destruction.

Julio: [00:07:08] Hay madera buena todavía, pero como nadie los controla, agarran este tipo de troncos y comienzan a cortar para sacar madera.

Juandi: [00:07:17] Well, the first thing he’ll say is that that fire was a man-made fire, as most of the fires that happen in Bolivia.

Steven: [00:07:25] Julio also told Juandi that timber traffickers create fires to facilitate deeper access to forests, which could otherwise not be reached. And they then pillage the forests of valuable trees like the almendro.

Juandi: [00:07:38] He said that this tree, the almendro tree, was exactly what they were looking for because that is a strong tree. And yeah, unfortunately, these strong trees may survive fires, but they cannot survive chainsaws.

Steven: [00:08:02] They do not survive the chainsaws. It was not surprising. Timber trafficking is a mainstay in the Amazon, and the almendro was huge. It can grow to 50 meters tall, with a circumference of up to 10 meters around the trunk. And it was also largely resistant to fire, so it’s perfect for building a house and window frames. This type of man-made fires were typical in this part of Bolivia. Where the Brazilian Amazon gets most of the international attention, fires have destroyed thousands of hectares in recent years in Bolivia as well.

Mafe: [00:08:36] And actually this was one of the thousand man-made fires set in Bolivia that get out of control due to high temperatures, strong winds, and the abundance of what firefighters called the natural fuel, which are the dry leaves and the dry sticks. Since 2016, some 60 million hectares have burned in Bolivia, and fires are, in fact, one of the main drivers of deforestation in the country.

Steven: [00:09:09] But as Julio told Mafe and Juandi, there was much more to this story. As it turns out, illegal logging is not the main goal of the criminals. In fact, it was much more a byproduct of another criminal activity: land trafficking.

Mafe: [00:09:23] Illegal logging has also been exacerbated by illegal settlements of people in protected areas or on public lands throughout the department of Santa Cruz. So what happened here is that, these people, this organized crime that are logging these trees are not necessarily going after the timber, but they’re going after the land. So the timber is just like a bonus. So it’s kind of a dos-por-uno, a two-for-one.

Steven: [00:09:59] In order to understand the two-for-one part of the story, we’ve got to go backwards. Over the years, while he was president, Evo Morales pushed numerous measures to incentivize economic development. Now, some of these measures targeted large industries, such as cattle or soybeans for export. Others were designed to push people in the highlands of Bolivia, such as the cities of La Paz and Cochabamba to move to the lowlands, places like Santa Cruz, where the fires would later take place.

The measures did three things for Evo Morales and his ruling party, the Movement Toward Socialism, or MAS, as it’s known by its Spanish acronym. First, it was a safety valve. It gave small farmers in the highlands a place where they could seek land elsewhere. Second, it furthered the government’s goal to develop areas on the edges of the Amazon. It’s not just cattle and soybeans. It’s also things like biofuels. But the third reason was much more political.

Newscast 6: [00:11:05] Santa Cruz había sido tradicionalmente un bastión opositor en Bolivia, pero este domingo sus votantes dieron una gran sorpresa y celebraron por primera vez el triunfo del presidente Evo Morales en este departamento.

Steven: [00:11:21] It moved the president’s supporters in the MAS party, who are traditionally in the highlands, to areas like Santa Cruz where MAS doesn’t have a lot of support. That shifted the electoral map, and by 2014, Morales was winning the election in Santa Cruz.

Mafe: [00:11:38] So this is a political strategy to bring or to move supporters down from the highlands to an area where they traditionally did not have support — that is, Santa Cruz — so they could change the political equation.

Steven: [00:11:55] This process happened quickly, which gets us to the two-for-one: timber trafficking and land trafficking happening at the same time and largely managed by the same corrupt and criminal networks. In these schemes, the fires are not an accident, but a key feature of the plans themselves to open up the land for development and to get the timber. Un dos-por-uno. The migration, in other words, is where the real money is. These migrants need land, and the criminals provide those moving from the highlands to the lowlands with this land.

Mafe: [00:12:32] And once they arrive in Santa Cruz, they clear forests through fires to make way for agriculture and cattle. But along the way, they also extract valuable species of wood. So the main goal is not even to get the timber but the land, and the timber is just a bonus.

Steven: [00:12:54] Part of the thing that’s making this hard to understand is that this program seems to be run from the central government. In other words, they’ve given them incentives to move down there and clear out this land. Is that the case? Am I understanding that correctly?

Mafe: [00:13:13] Yes, that’s exactly the case. The government has prioritized the economic development of the country based on agriculture and cattle. But this obviously took a high cost on the environment that resulted in high levels of deforestation.

Steven: [00:13:30] Under normal circumstances, transferring this land to colonizers would take months, if not years. But the government’s land agrarian institute, or INRA, as it’s known, is notoriously corrupt, and many activists and crime watchers in Santa Cruz told Mafe and Juandi that they are part of an elaborate scheme to help both MAS and themselves in the process.

Juandi: [00:13:53] There are huge corruption schemes where INRA officials, fixers, and squatters all work in an organized crime network: where squatters, to get access to the land, pay a fee to the fixers, and they connect them to the INRA officials or the former INRA officials to get ownership of the lands.

Steven: [00:14:12] Mafe and Juandi also said the brokers sell to large agricultural and cattle farmers, who also get land titles expedited by corrupt INRA officials.

Mafe: [00:14:23] And the other way is that these land trafficking networks are just invading and accumulating lands in Bolivia, but they don’t even get the titles. They don’t even bother to get the titles, but they just accumulate land, and then they pass on these lands to different people who are colonizing as well, in a way.

Steven: [00:14:48] This colonization accelerated through 2019, as did government measures to facilitate it. On July 9, 2019, for example, the Morales government passed a measure allowing small fires in Santa Cruz and the neighboring state of Beni. It was one of many he had passed over the years that facilitated these fires, which helped the colonizers clear the area they wanted to develop. Just two days later, the local fire watch issued a warning saying the fires were starting to burn out of control. The next day, Santa Cruz registered the largest number of fires ever. By then, Julio and the other volunteer firefighters were already scrambling to get those fires under control.

Julio: [00:15:31] El 2019 fue crítico. Ese fue lo peor.

Steven: [00:15:35] 2019 was critical, Julio told Mafe and Juandi. It was the worst.

Mafe: [00:15:40] In early August, some 500 fire outbreaks were recorded in Santa Cruz, but in less than two weeks, that number jumped to more than 15,000. And this is why people like Julio or other civil society people that I met there are so important to fight the fires and also to fight environmental crime in Bolivia.

Steven: [00:16:07] They’re literally the firewall. I mean, it’s amazing. I mean, Julio is part of the firewall. How many of these volunteer firefighters are there out there?

Mafe: [00:16:21] At the time, they received like 360 volunteer firefighters. They arrived in Bolivia from the rest of the country and from different parts of the world. One of these was Senia.

Steven: [00:16:41] At the time. Senia was a 50-year-old housewife living with her husband and her children in Santiago de Chiquitos, Santa Cruz. So, she was accustomed to fires in her area. She herself had started fires, the small fires to clear brush or revive a patch of land. But the 2019 fires blanketed her house with smoke.

Senia: [00:17:02] Vengo de estar compartiendo y preservando nuestro medio ambiente.

Mafe: [00:17:06] In 2019, she told us that she was at her home looking at the fires and she said, I cannot sit here and do nothing. And she told her husband, we have to do something. And [she told] another 20 women in the town, and she encouraged all of them to join the firefighters.

Senia: [00:17:29] Entonces me reuní unas 20 mujeres.

Steven: [00:17:33] After a short training, they found themselves fighting fires. Senia was the leader. And she told the other women, ‘Let’s go! Let’s go protect our forest!’

Senia: [00:17:42] Y les dije, ‘Vamos, acompañemos a los bomberos. ¡Vamos! Seamos parte de la protección de nuestros bosques.’

Newscast 7: El fuego avanza en la zona oriental de Bolivia y hasta ahora habría devorado alrededor de medio millón de hectáreas, según informes oficiales de la Gobernación de Santa Cruz, que declaró desastre departamental.

Steven: [00:18:05] It wasn’t easy. As Julio describes it, the fires that year ran wild.

Julio: [00:18:12] Pero el 2019 era — lo raro era que, era fuego aquí, fuego acá. En Roboré tenías nueve, diez, 11, 12, 15, 25 incendios. No focos de calor. Incendios forestales.

Steven: [00:18:26] In one area called Roboré, they began counting the fires: nine, 10, 11, 12, 15, up to 25. Not brush fires, he said, real fires. We would put them out in one place, and they would pop up a few kilometers away in another.

Julio: [00:18:43] Apagaba este, aparecía otro acá, a tres kilómetros del que apagaste. Pero ninguna relación con, mirando el satélite andando, de cómo pudo haber llegado ese ahí.

Steven: [00:18:52] Meanwhile, Senia and the other volunteers were doing whatever they could to help. They carried food and water to the front lines, sometimes on their shoulders or on their heads. Others acted as nurses or cooks.

Senia: [00:19:04] Cuando cocinamos, no había acceso de movilidad. Al hombro, a la cabeza, llevamos la olla, llevamos … los apoyábamos con agua, con comida, y si era posible, también nos metíamos [al fuego]. También nos metíamos [al fuego].

Steven: [00:19:19] The work went on for weeks. Volunteers like Senia felt helpless, and she prayed that nothing would happen to her fellow volunteers.

Senia: [00:19:27] Y con esa pena de que a alguna señora le pase algo, estaba bajo mi responsabilidad. Entonces yo pedí al Señor que nada le pase a las mujeres porque había rato que me daban ganas de llorar, de ver esa impotencia que no podíamos hacer nada.

Steven: [00:19:43] She actually wanted to cry, she told them, but the other women, they pushed her to keep going.

Senia: [00:19:48] Y las señoras que estaban a mi cargo decían, ‘No, doña, vamos! Nosotros podemos’. Entonces me animaban. ‘Yo cargo esta mochila! Yo cargo esta pala. Vamos a ayudar!’

Steven: [00:20:01] ‘Let’s go!’ they said. ‘We can do it! Grab that backpack. Grab that shovel. We’re going to keep going.’

Senia: [00:20:06] Ese apoyo, y me daban ánimo a seguir adelante. Entonces la verdad es que tuve que seguir adelante por esas mujeres y por mí.

Steven: [00:20:18] It gave her hope, she said.

Steven: [00:20:24] Eventually, with the help of the federal government, they were able to control the fires. It was ironic. This was the same government who was incentivizing the colonizers to burn the area and pay off corrupt officials to get the land titles. Juandi said they used backhoes and other big machines to carve out gullies and squeeze the fire against the river.

Juandi: [00:20:46] They start to isolate the fire. It’s not just putting water onto the fire because many times that is not helpful because of the wind, because of the water, because it is too hot in the environment. The success of eliminating a fire also relies on these big trenches to isolate the fire. So that was what they were also doing there.

Steven: [00:21:08] The fire was out, but for Senia, nothing was the same. She eventually decided to train and become a regular firefighter. Soon, she was the head of her firefighting unit.

Juandi: [00:21:21] They have like these big yellow suits, with a helmet on, and a bag — a really, really big bag where they carry the gallons of water — that is connected to some kind of manguera so they can spray the fires, and they could diminish the fires.

Steven: [00:21:40] Manguera, that’s a hose. Senia’s firefighting unit has between 15 and 20 people. Each member has personal protection equipment, so suits, gloves, boots, glasses. These shield them during their eight to 24 hour workdays they have to face.

Juandi: [00:21:57] And a funny part of it was that we were speaking to Senia at the hotel, and she was like this sweet old woman — she could be my grandmother. But she was showing us photographs, selfies of herself with the fires behind her. It was like this was our painting of her being so proud, so proud of having made that decision that we are going to fight this ourselves. Actually, we don’t need the government. We’re going to, as a community, we’re going to fight this ourselves.

Steven: [00:22:30] Senia drafted her husband and other neighbors to join as well. It’s difficult and dangerous work. She hurt her arm, for example, when a burning branch tumbled on top of her. But she says the hardest part is walking for kilometers and kilometers with 20 kilograms of water on her back. But she’s pretty committed.

Senia: [00:22:47] Nosotros como bomberos tratamos de cuidar, y pues frenar un poco los avasallamientos y la deforestación, que es muy dañino para todo.

Steven: [00:23:02] The war against the fires, against the government, against organized crime and the many faces it takes, is an impossible task for people like Julio and Senia to take on.

Mafe: [00:23:15] I left Bolivia impressed by the people that we met, that is like the first line of defense against the organized crime that is destroying the Amazon in Bolivia and the forests in Bolivia. It was impressive to see these people that are fighting alone this huge threat.

Steven: [00:23:38] It’s a tough road ahead, though, for them. I mean, between Julio and Senia, I wish them all the best. But, it seems like they’re fighting forces that are a little bit bigger than they are. I mean, all the way from the presidency down to timber traffickers and land traffickers getting their two-for-ones and selling their land. And you know, it’s an uphill battle.

Mafe: [00:24:01] But you know what, Steve, their commitment to the defense of the forest, I think it’s much more important for them and their encouragement to move forward in this task of being a firefighter. It’s stronger than everything else.

Steven: [00:24:31] This show is a co-production of InSight Crime and La No Ficción. This episode was produced by me, Steven Dudley, with help from Elisa Roldán. Special thanks to our reporters, María Fernanda Ramírez and Juan Diego Cárdenas. And of course, to Julio and Senia for sharing their stories. Our editors are Elisa Roldán and Tomás Uprimny. Our sound designer, Valentina Fonseca, and our graphic designer, Isabela Soto.

InSight Crime is a nonprofit think tank and media organization, and the work we do is rigorous and costly. So please, consider supporting us with a donation, so we can keep telling these important stories.

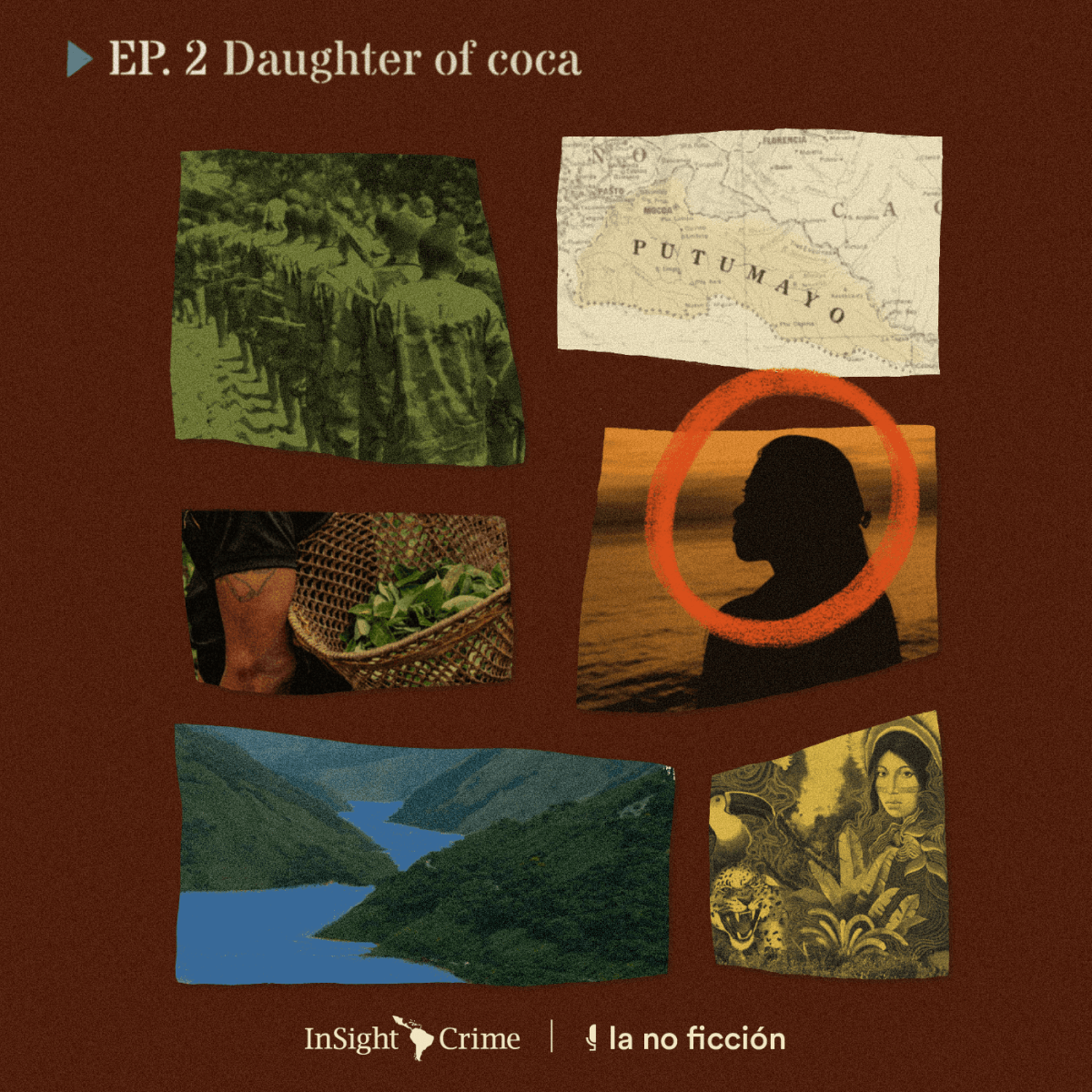

We’ll be back in a couple of weeks with a story from Colombia about a small coca grower who teaches an important lesson about how coca gives, and cocaine takes away.

Julio: [00:25:11] Yo prefiero la abeja africana que la veo. Se te mete adentro del ojo aquí. Aquí adentro se te mete. No respeta la boca. La nariz.

Steven: [00:25:22] Thanks for listening. See you next time.

Did you enjoy this episode?

We want our content to remain free. Please consider donating to support our work. Every little bit helps.

In-Depth

Since 2019, Bolivia has grappled with the formidable challenge of managing and preventing forest fires, a complex confluence of natural factors, human interventions, and the escalating impacts of climate change. The latest updates underscore an ongoing and concerted battle against the flames, with a strategic focus on prevention, preparedness, and swift response mechanisms.

Over the past three years, these wildfires have exacted a toll on Bolivia’s ecosystem, imperiling Indigenous territories, disrupting peasant communities, and casting a shadow on society at large.

In 2022, Bolivia’s environmental landscape was marked by two prominent issues: the alarming progression of deforestation, ranking the country second among nations facing the greatest forest loss in Latin America, and the surge in gold mining within protected natural areas and indigenous territories.

While not surpassing previous years’ figures, Bolivia ravaged over 800,000 hectares of vegetative cover, according to the Ministry of Defense.

Equally noteworthy, a report from the Bolivian government on October 29, 2023, reveals that over 2.6 million hectares of land were engulfed in flames during the year. While this marks a substantial reduction from the critical situation in 2019, the flames are still scattered throughout Bolivia.

Our coverage of environmental crimes does not stop. On March 20, we will publish our new in-depth investigation, “The Roots of Environmental Crime in the Bolivian Amazon.” In this investigation, we will delve into the criminal economies that have ravaged Bolivia’s Amazon region: land trafficking, timber trafficking, illegal mining, wildlife trafficking, and drug trafficking. Follow us on social media and subscribe to our newsletter to stay up to date.

Dig Deeper: Bolivia and Environmental Crime

Colombia’s Historic Drop in Deforestation Could Be Linked to Criminal Groups

Deforestation in Colombia has fallen to its lowest levels in 23 years, suggesting the government’s fight against environmental crime has yielded results.

…

The Mafias Behind Sand Trafficking in Latin America

Criminal mafias are making massive profits from the illegal extraction and sale of sand for construction purposes.

Illegal sand extraction causes environmental damage,…

Cocaine Surge Fuels Violence as Opium Falls: UN Drug Report 2024

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) released its annual drug report, highlighting the manifold destruction caused by a surging cocaine…

Episode Credits

This show is a co-production of InSight Crime and La No Ficción.

Produced and written by Steven Dudley with the help of Elisa Roldán

Edited by Elisa Roldán and Tomas Uprimny

Reporters: María Fernanda Ramírez and Juan Diego Cárdenas

Sound Design by Valentina Fonseca

Cover Illustration by Isabella Soto

Thanks to Julio and Senia for sharing their stories.

Explore Our Investigations