A decline in drug trafficking in northern Colombia has led to a rise in extortion as increasingly fragmented criminal groups seek new sources of funding.

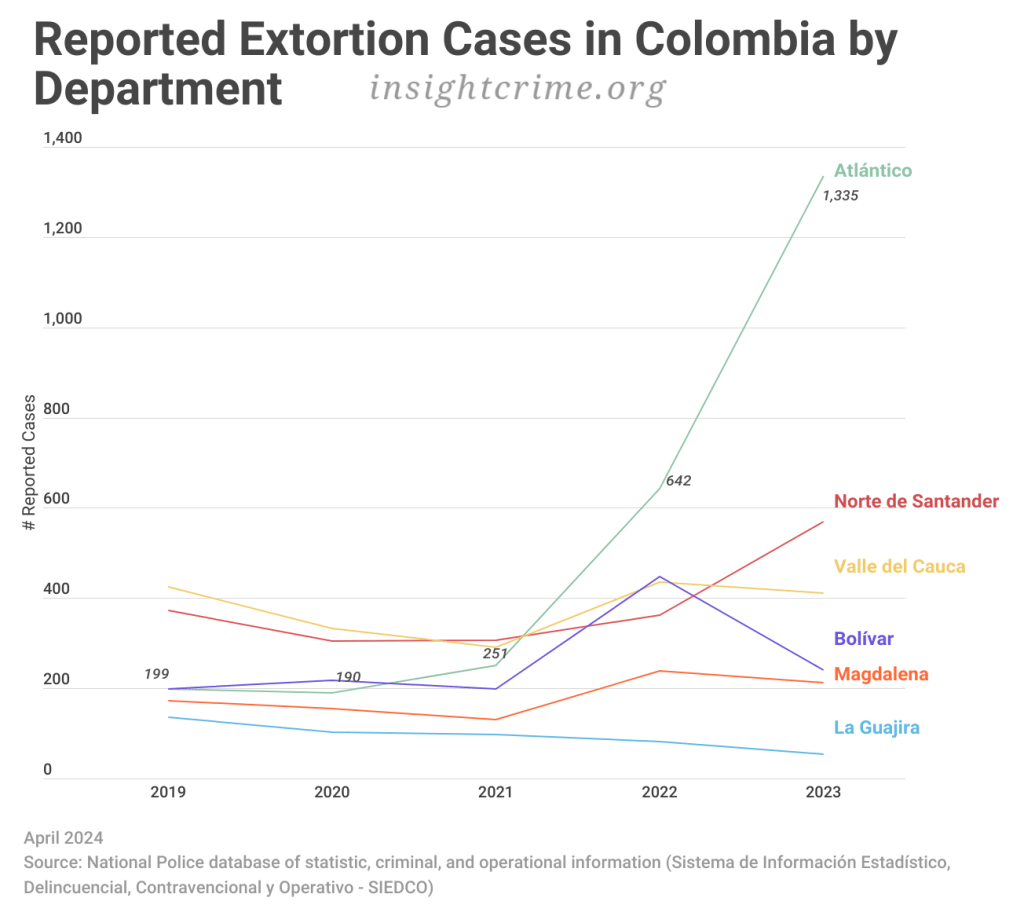

Reports of extortion in the department of Atlántico, Colombia, rose from 199 in 2019 to 1,335 in 2023 — a 570% increase — according to the national police database (Sistema de Información Estadístico, Delincuencial, Contravencional y Operativo – SIEDCO). The cases are concentrated in the metropolitan area of its capital, Barranquilla. The national police has sent hundreds of officers to help Barranquilla’s forces confront this issue.

SEE ALSO: Gang Killings of Bus Drivers Paralyzes Colombia’s Fourth City

The rise in extortion “primarily affects merchants, shopkeepers and transport workers,” said a report by the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation. According to the investigation, the criminal groups involved include the Gaitanistas – also known as the Gulf Clan, one of Colombia’s dominant drug trafficking groups – as well as smaller organizations such as the Costeños, the Pepes, and the Rastrojos Costeños.

Atlántico was the department with the highest increase in extortion complaints in the country over the last four years. Meanwhile, in other departments in northern Colombia, such as Bolivar, La Guajira, and Magdalena, as well as departments elsewhere with a significant criminal presence, such as Norte de Santander and Valle del Cauca, extortion complaints remained relatively stable.

InSight Crime Analysis

The increase in extortion in Atlántico is primarily the result of two factors: a reduction in cocaine trafficking during the COVID-19 pandemic and the fragmentation of criminal groups.

When cocaine trafficking decreased during the pandemic, smaller local criminal groups that acted as logistical operators for the Gulf Clan lost a significant portion of their revenues.

“They needed to replace those national revenues with local revenues,” Luis Fernando Trejos, a professor in the Political Science and International Relations department at the University of the North, told InSight Crime.

“When the quarantines were relaxed … local criminal organizations began to compete for the economies that were left standing,” he added.

SEE ALSO: Colombia Struggles to Tackle Prison-Based Extortion

Meanwhile, these local criminal groups also began to fragment.

“From the Costeños, come the Rastrojos Costeños, and then the Pepes. It’s no longer just one organization extorting, now others are competing for control of that income,” said Trejos.

Unlike large-scale drug trafficking, which requires an extensive network, smallercriminal groups can easily carry out extortion schemes, often using technology to reach and rob their victims.

“You don’t need huge numbers and territorial control. Just a small group — even two people on a motorcycle — who can pressure [victims] for the extortion payment, shoot at a business, or simply leave a note,” said Trejos.

Featured image: National police reinforcements in formation in Barranquilla. Credit: La Vibrante