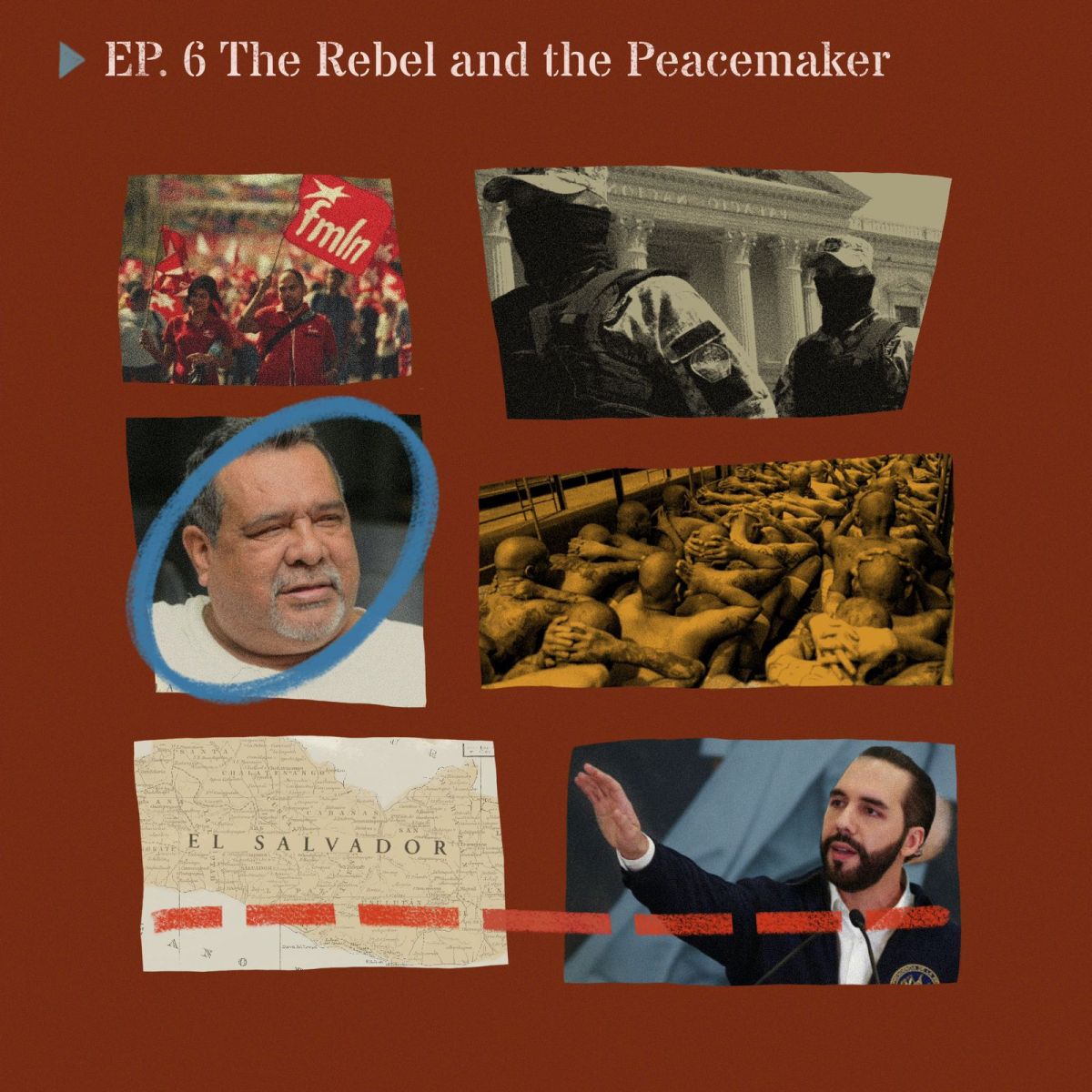

Crime Strengthens Crime

The rise of the biggest gang in the southern hemisphere and a Brazilian judge that still believes in justice.

In this episode, we talk to Ivana David, a Brazilian judge who has had a front-row seat to the creation and the evolution of the region’s largest criminal organization, o Primeiro Comando da Capital, or PCC, as its known for its Portuguese acronym. The judge has spent her life trying to combat the forces responsible for the group’s incredible rise to power and has some unexpected takeaways from that journey.

Listen on

Transcript

Steven: [00:00:00] On the afternoon of March 14, 2003, a Brazilian judge named Antônio José Machado Dias left a courthouse in a city called Presidente Prudente in the southeastern state of São Paulo. Antônio Machado, or Machadinho, as people like to call him, was one of the judges responsible for the vast São Paulo state prison system. Since São Paulo had close to a third of all Brazil’s prison population at the time, Antônio’s job was difficult. It included investigating prison abuses and signing off on transfers between regular prisons and maximum security prisons where some of the most dangerous criminals in Brazil were held.

For his work, Antônio had received threats and had an occasional security detail, but he often didn’t use it, especially when he had to travel from the headquarters of the state judicial system, the city of São Paulo, which goes by the same name as the state, to far away places like Presidente Prudente, which is a few hundred kilometers away. Besides, in Brazil, there wasn’t a history of attacks on judges.

So as he got into his black Vectra, he had little reason to worry. But on that day, not long after he began driving, he was intercepted by a white Fiat Uno that swerved into his lane. In his attempt to avoid a collision, he turned his car onto a curb and hit a tree. As Antônio struggled to get out of his badly damaged vehicle, a passenger from the Fiat, which had stopped, approached the Vectra with a nine millimeter handgun and shot the judge three times, including once in the chest and once in the head, killing him on the spot.

Meanwhile, back in the city of São Paulo, another judge, Ivana David, was in her office. Judge David had basically the same job as Judge Machado, so if someone was going after him, it wasn’t unreasonable to think that she too could be a target. Years later, Ivana told me she remembered the moment she found out about her colleague’s death. It was almost like it was yesterday, she said.

Judge Ivana: [00:02:21] Eu lembro que, eu lembro direitinho …

Steven: [00:02:24] It was about six or seven in the evening, and a call came through: “Are you sitting down?”

“Yes,” she said. “I’m sitting at my desk.”

“Something terrible has happened. Judge Machado has just been assassinated.”

Judge Ivana: [00:02:40] O juiz Antônio Carlos Machado foi assassinado.

Steven: [00:02:41] “What?” Ivana said. The person on the other end of the phone relayed the gruesome details: the crash, the body slumped over the steering wheel, the coup de grâce. She was stunned.

Judge Ivana: [00:02:54] Eu confesso que eu fiquei transtornada, a gente nunca tinha vivido isso.

Steven: [00:02:57] She later collected herself. But she knew something had changed for the worse. Something was different now. As she told me, she had never felt the power of a criminal act so personally and so profoundly.

Judge Ivana: [00:03:12] Foi a primeira vez que a gente sentiu essa força tão grande.

Steven: [00:03:19] Welcome to InSight Crime’s podcast, where we investigate from the ground up to help you understand how organized crime works in the Americas. I’m your host Steven Dudley, InSightCrime’s co-director.

In this episode we talked to Ivana David, a Brazilian judge who has had a front-row seat to the creation and the evolution of the region’s largest criminal organization, o Primeiro Comando da Capital, or PCC as it’s known for its Portuguese acronym. The judge has spent her life trying to combat the forces responsible for the group’s incredible rise to power and has some unexpected takeaways from that journey.

I spoke to Ivana back in 2019, but I thought about her after a recent series of prison riots in Ecuador. The riots came after the new government announced an offensive against the country’s criminal organizations and a transfer of top criminal leaders to maximum security facilities. The government claimed it would squelch the gangs with force both inside and outside of prisons, and the gangs responded.

Newscast 1: [00:04:35] Ecuador roiled by violence as gangs and terror groups stir up chaos nationwide.

Newscast 2: [00:04:40] The latest outbreak of violence in Ecuador …

Newscast 3: [00:04:41] Inmates in rival gangs using machetes and grenades. Nearly 120 people killed.

Newscast 4: [00:04:45] It is the latest in a series of deadly riots inside Ecuador’s prisons.

Newscast 5: [00:04:50] … has declared a state of emergency to deal with a wave of riots and crackdowns.

Newscast 6: [00:04:54] You could be forgiven for asking what’s happened to Ecuador.

Steven: [00:04:57] They overran prison blocks in various parts of the country, and took numerous guards hostage, as well as burned cars in the streets and ransacked a television channel while it was broadcasting live.

Newscast 7: [00:05:12] This is the chilling moment when armed men stormed the set of a public TV channel in Ecuador, firing off guns and waving apparent explosives …

Steven: [00:05:19] Ecuador’s most well-organized criminal gangs got their start in prisons. They have since become the base from which they can coordinate criminal activities: pay bribes to police, politicians, judges, and prosecutors, and launch full-on sophisticated assaults on rivals and the state.

These types of operations have become all too familiar in the Americas from the United States to Colombia, Bolivia, Venezuela, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. At InSight Crime, we’ve tracked criminal dynamics in all of these places, and we’ve found they all have something in common. Some of the most important leaders are in jail, and often the most powerful criminal groups run their operations from their prison cells.

Nowhere is this more true than in Brazil. And perhaps no one knew this better than Judge Ivana David.

Ivana told me she first noticed something different was happening in the prisons around the year 2000. At the time, she was working as a judge for internal affairs.

Judge Ivana: [00:06:30] Se o preso revelasse qualquer tipo de lesão, eu, como juíza, tinha que chamar esse preso para saber o que aconteceu …

Steven: [00:06:36] When a prisoner was beaten or tortured and filed a formal complaint, Ivana would go to the jails and get that inmate’s testimony directly.

Judge Ivana: [00:06:43] E eu era a única mulher.

Steven: [00:06:46] She was the only female judge at the time and close to thirty years old.

Judge Ivana: [00:06:49] Imagina eu com 30 anos ou menos. Uma menina.

Steven: [00:06:52] But she said she didn’t have any problems. The key, she said, was treating the prisoners with respect and never hiding what her function was — administering justice.

Judge Ivana: [00:07:02] Nunca, nunca tive problema com preso, um preso nunca me desrespeitou.

Steven: [00:07:08] As she talked to the inmates, she realized something was happening. One group was kidnapping new prisoners and holding them for ransom inside the prisons. That group, she found out later, was the PCC.

Judge Ivana: [00:07:21] O Primeiro Comando da Capital.

Steven: [00:07:27] Prison gangs in Brazil had a peculiar history. During Brazil’s last military dictatorship, between 1964 and 1985, the jails were filled with political prisoners who were mixed with criminals. Ivana told me the two mingled, and soon the criminals were developing an ideology that centered on prisoners’ rights and improving prison conditions.

Judge Ivana: [00:07:51] São dois mundos que se encontram.

Steven: [00:07:53] Out of this came the country’s prison gangs. The first of them was known as Comando Vermelho, or Red Command, which emerged in the prisons of Rio de Janeiro in the 1970s.

Judge Ivana: [00:08:05] E também nasce de um envolvimento de presos comuns com presos políticos na Ilha Grande.

Steven: [00:08:11] Ten years later came the PCC, whose birth is traced to a prison uprising in 1992, in what was then the country’s largest prison system in the state of São Paulo.

Newscast 8: [00:08:22] Os presos fizeram fogueiras e queimaram roupas e colchões. Toda a região estava cercada. Quando a polícia resolveu agir, o resultado foi trágico.

Steven: [00:08:32] In the brutal crackdown that followed, at least 111 inmates were killed.

Newscast 9: [00:08:37] A maior chacina de presos em todo o mundo.

Steven: [00:08:42] Out of this came a group: the Comando da Capital, the Capital Command. It organized around fighting what it called “the oppressors.” This meant the government, of course, but also society writ large, which they felt had excluded them. The ideology struck a cord. Not just inside prisons, but in huge parts of Brazil, a country that is one of the most unequal on the planet and a place where repression and police killings are commonplace.

They drew up a constitution and a set of rules. This included prohibiting rape and sexual assault in the prisons. But it wasn’t just about protecting each other. They also enveloped you like a family would. New initiates were baptized. They called each other “brother,” and, like blood relatives, they required a lifetime commitment.

They were also violent. From the beginning, anyone who crossed them got killed. In 1993, they organized a soccer match with a rival gang. But instead of playing, they ambushed the opposing team, then cut off the heads of their leaders before leaving them on the pitch. Shortly thereafter, they changed their name to Primeiro Comando da Capital, or the First Capital Command.

The PCC quickly expanded, and by the time Ivana started hearing about them, although the government did not officially recognize them yet, they were committing horrendous acts of violence against any would-be rival.

Judge Ivana: [00:10:14] Então a gente começa a ver as mortes …

Steven: [00:10:18] She said that, at one prison, she saw a severed head without the eyes, perched on a flagpole.

Judge Ivana: [00:10:23] A hora que eu entrei eu vi no mastro uma cabeça colocada no lugar da bandeira.

Steven: [00:10:29] The PCC would also cut out the tongues of alleged snitches, she said, and even extracted the hearts of their enemies. As Ivana told me, if you had no heart, then you weren’t fit to be a member. It was a symbol of their control and a very effective terror tactic.

Judge Ivana: [00:10:45] Uma das marcas dessa facção é, por exemplo, tirar o coração.

Steven: [00:10:49] The terror gambit worked, and soon the PCC had taken control of nearly the entire prison system of the state of São Paulo. Evidence of this came in February 2001, when the PCC launched what it called “the mega rebellion,” taking over 29 prisons at once.

Newscast 10: [00:11:07] Tudo começou no final do horário de visitas. A rebelião terminou nove horas depois. O movimento seguia as ordens do Primeiro Comando da Capital.

Steven: [00:11:16] The mega rebellion was a sign that the PCC was moving to stage two: that of direct confrontation with the government. Authorities had finally begun talking openly about the criminal group and targeting its most lucrative criminal activities, namely bank robberies. In the process, it had arrested the person who later would become its leader: Marcos Willians Herbas Camacho, alias “Marcola,” an infamous bank robber.

It was Marcola, Ivana said, who had organized the hit against her friend and colleague, Judge Antônio José Machado Dias, as he drove from Presidente Prudente de São Paulo on March 14, 2003.

Judge Ivana: [00:11:59] A motivação não tem nada a ver com a facção. A motivação tem a ver com a execução da pena do irmão do Marcola.

Steven: [00:12:06] Ivana said the attack was personal. Marcola targeted Antônio because he was making sure that Marcola’s brother, who was in another prison, would have to carry out his sentence. But the impact was institutional.

Judge Ivana: [00:12:18] Eu sempre recebia ameaças no fórum, que iam me metralhar, que iam me matar …

Steven: [00:12:24] I was getting threats constantly that they were going to kill me, she said. That they knew where I lived, that they had information about my daughter.

Judge Ivana: [00:12:32] O momento não era um momento muito fácil. Era a primeira vez historicamente que se matava um juiz no estado de São Paulo.

Steven: [00:12:39] It was a very difficult time because they had never killed a judge in the state of São Paulo, which is Brazil’s most populous state. But it was about to get worse.

As Ivana and other authorities amped up their efforts to control the PCC inside the prisons with transfers and isolation of certain prisoners, the criminal organization amped up its efforts to squeeze the government on the outside. Ivana said she started receiving a constant barrage of threats.

Judge Ivana: [00:13:12] De tudo quanto é jeito, ligavam do fórum, ligavam em casa. Era um inferno.

Steven: [00:13:15] They called her work, her house. “It was hell,” she said. We didn’t have cell phones, we had beepers, but still, they sent threats, she said. Even dropping notes under the door.

The government, however, kept pushing. It isolated more leaders and announced that it was transferring some 750 PCC members to different prisons. The PCC responded, orchestrating a series of riots inside the prisons and attacks across the city of São Paulo, beginning on Mother’s Day 2006.

Newscast 11: [00:13:48] Escutas telefônicas revelaram que a organização criminosa planejava realizar rebeliões em diversos presídios durante o Dia das Mães.

Steven: [00:13:59] Over the next few weeks, 59 law enforcement were gunned down.

Newscast 12: [00:14:03] The gang behind the police murders is believed to be Brazil’s notorious First Capital Command.

Steven: [00:14:09] The government’s response was even more brutal. At least 505 civilians were killed. A later investigation by a prominent state university said that, of these civilian deaths, 118 were killed in so-called confrontations with police, while another 88 were killed by masked and unmasked vigilantes. It was as if, even amidst the PCC-led uprising, the government was reinforcing the PCC’s argument that they were the oppressors of the people.

Newscast 13: [00:14:41] São Paulo has long been known as a violent city. But the fear is that this recent spate of murders might be the beginnings of an undeclared civil war between organized crime and the police.

Steven: [00:14:54] Ivana took a different lesson from the events. For her, this was proof that the PCC would not be confined to operating behind the walls of the prisons.

Judge Ivana: [00:15:04] Não está limitada aos muros do presídio …

Steven: [00:15:07] Soon, their domain would be the entire country.

During the time the PCC was first expanding, prisons in the Americas were going through a massive transformation. Following the lead of the United States, which had successfully lowered violence and criminality in part by incarcerating people at some of the highest rates in the world, countries all over the region began jailing suspected criminals and convicted prisoners at unprecedented rates. Between the years 2000 and 2010, the incarceration rates doubled in El Salvador and Venezuela. In Colombia, they went up by 60%. In Ecuador, by 50%. And in Brazil, during the same time period, the incarceration rate went up by 100%.

But while they were adding prisoners, these governments were not adding personnel, infrastructure, or measures to deal with the newly incarcerated at nearly the same rate. Prison gangs exploded, and so did the violence inside prisons. The MS13 and the 18th Street gangs in El Salvador, for example, fought numerous bloody battles for control of the prisons where they were held. In response, the government split the gangs, moving them into their own separate prisons. With their de facto respite secure, the gangs got stronger.

In Brazil, the authorities tried the opposite strategy. They sent the PCC to other states, or kept them mixed in the general population, thinking they could dilute their power. This plan also backfired. The PCC spread at an alarming rate. A few years after the 2006 Mother’s Day uprising, Ivana began traveling to different parts of the country where, to her surprise, she found the gang’s tentacles reached hundreds of kilometers from their birthplace.

Judge Ivana: [00:17:07] Eu fui pra Bahia por exemplo, eu fiquei um mês na Bahia …

Steven: [00:17:10] One of her first stops was the northeastern coastal state of Bahia. There, she spoke to numerous PCC members in prisons.

Judge Ivana: [00:17:20] Lá já tinha facção. E como …

Steven: [00:17:20] One of them, she said, had been released or escaped, then recaptured in Bahia. And almost like a missionary, the PCC member had evangelized his fellow inmates with the PCC gospel: No to the state oppression; yes to protection from your new family. Many of them, she said, had become members of the PCC.

Judge Ivana: [00:17:42] Eu fui para a Bahia, eu fui para o Rio de Janeiro e já tinha.

Steven: [00:17:45] When she visited other places, she found the same thing. From Rio de Janeiro in the south to the Amazon up north, the PCC was spreading throughout the country.

The PCC won over inmates in many ways that went well beyond their ability to inflict gruesome acts of violence on their rivals.

Judge Ivana: [00:18:08] E nessas audiências, quando os presos vinham conversar comigo, eles começavam a contar …

Steven: [00:18:13] The prisoners told her how they had to pay a tax on the inside and how that translated into a kind of support network on the outside. If the wife of a PCC member was pregnant, for example, then they would give money for a taxi to get her to the prenatal checkup.

Judge Ivana: [00:18:34] … o representante era quem pagava um táxi.

Steven: [00:18:35] For those of us who have not been in prison, it’s difficult to fathom how important it is for prisoners to feel like their family is taken care of on the outside, and how important it is for them to maintain connections to that world from the inside. The PCC understood this perfectly and harnessed these feelings to their advantage.

Judge Ivana: [00:18:56] Ele garante para o preso que vai cuidar da sua família.

Steven: [00:19:01] They not only paid small expenses, they also facilitated visits and regulated security during those visits to make sure no one was assaulted or worse.

Over time, the organizations set up what they referred to as “sintonias,” or committees. The PCC has committees for nearly everything. The sintonia de ajuda, or help committee, for example, was the one that assisted families with expenses, like the cost of the taxi for prenatal care at the hospital. There are sintonias for the different criminal economies they manage and to help them administer their membership, their finances, and their internal discipline. There’s a sintonia that provides basic supplies for prisoners — things like toothbrushes and toothpaste. Another that provides lawyers. Another that takes care of logistics and expenses for family members who want to visit loved ones in far away places, including lodging, transport, and food. As Ivana told me, they take care of both the emotional and the financial needs of the prisoners.

The PCC also has a peculiar way that it manages its factions. From the beginning, as a counter to Brazil’s vast inequities between the rich and the poor, and a response to the oppressive way the state administered justice, it espoused what it called “igualdade,” or equality. What this means in practice is that the organization is more horizontal than hierarchical. When someone breaks a rule, it holds debates, or a form of court proceedings, where a group of prisoners decides the outcome and the penalty.

The PCC rotates leaders frequently inside and outside of the prisons, and seeks to forge consensus rather than issuing top-down directives. Its factions have widespread independence as long as they do not break some basic rules and always give some of the proceeds to the upper echelon. To be sure, Marcola remains the leader of the PCC or, as Ivana says, the CEO.

Judge Ivana: [00:21:16] É como se fosse o grande CEO, o representante da empresa …

Steven: [00:21:19] But Marcola is part of a board of directors, and like the other senior members, he has a single vote when the board has to come to an important decision. Below this board is the criminal structure, which is organized into cells that do not interact with one another. The PCC is, in other words, a kind of network of criminal entrepreneurs. Akin to a secret society like the Masons, it’s able to undertake national strategies and support one another, but also acts on a local level very independently of one another. As they like to say, o crime fortalece o crime — crime strengthens crime. This amorphous and compartmentalized aspect of the PCC, as well as its use of the committees, makes the job of law enforcement very difficult.

Judge Ivana: [00:22:10] Por exemplo, uma sintonia dos gravatas necessariamente não conversam com a sintonia financeira.

Steven: [00:22:17] That means that if I’m talking to a person in one committee, they have no knowledge of who is in the other committee, Ivana said. Specifically, she cited the example of a group that commits large-scale theft of cargo and trucks, a major activity of the PCC.

Judge Ivana: [00:22:34] Hoje, por exemplo, roubo de carga é uma estrutura, como é uma facção criminosa.

Steven: [00:22:40] Whoever robs the truck, she said, is not the same group that got the weapons to rob the truck.

Judge Ivana: [00:22:46] Quem rouba o caminhão com a carga não é a mesma pessoa que locou a arma.

Steven: [00:22:52] Nor the same group that’s going to sell the stolen goods.

Judge Ivana: [00:22:55] … que não é a mesma pessoa que vai vender a carga, que não é a mesma pessoa que vai desmontar o caminhão …

Steven: [00:23:01] In the end, no one who they captured that is part of this structure can tell her the beginning or the end of the story.

Judge Ivana: [00:23:10] … eu prender qualquer uma dessas partículas eu não descubro nem o antes e nem depois.

Steven: [00:23:16] What investigators also missed was that the PCC was getting ready to take yet another step up in the criminal world.

In 2017, alias Marcola appeared before a tribunal to testify in a PCC case.

Tribunal: [00:23:37] O nome inteiro do senhor.

Marcola: [00:23:38] Marcos Willians Herbas Camacho.

Steve: [00:23:40] Unlike other CEOs, the PCC’s Chief Executive Officer does not give interviews or appear in public forums, so it was rare to see him and hear his voice.

Marcola: [00:23:52] Bom dia, doutor.

Steven: [00:23:57] Even so, the hearing was hardly revealing. During the question and answer session, Marcola repeatedly denied that he is a leader or even a member of the PCC.

Tribunal: [00:24:08] Você faz parte do PCC?

Marcola: [00:24:10] Não.

Tribunal: [00:24:10] É integrante do PCC?

Marcola: [00:24:12] Não.

Steven: [00:24:12] While he admitted he knew who the PCC leaders were, he claimed that his conversations with them happened because they were in a dispute, and that he was defending himself and his family.

Marcola: [00:24:25] Tenho três filhos pequenos para criar, eu tenho que ter suavidade com a minha família. E era isso que eu fazia …

Steven: [00:24:33] Ironically, at the time he testified, Marcola and the PCC were arguably stronger than ever. They had as many as 30,000 members spread across almost a third of Brazil’s states. They controlled giant portions of the increasingly lucrative local drug markets and the contraband cigarette trade. The government kept battling, of course, but it couldn’t win. The more PCC it incarcerated, the stronger the group got inside the prison system. The PCC had also started to make bold moves to expand outside of Brazil, most notably in neighboring Paraguay, where they had become a major player in the cocaine and marijuana transportation markets.

Newscast 14: [00:25:16] Lo que vamos a ver va a ser lo siguiente: Vemos esta camioneta, pero ahora lo que va a llamar la atención es lo que tiene adentro. Lo que tiene adentro es una antiaérea, una ametralladora …

Steven: [00:25:27] A couple of years earlier, the PCC, using a .50 caliber Browning machine gun that was specially mounted like a turret on the back of an SUV, ambushed the most powerful underworld figure in the Paraguayan city of Pedro Juan Caballero, blasting through the front windshield of his armored vehicle and leaving him dead in the driver’s seat.

Newscast 15: [00:25:50] Es una ametralladora que comenzó a usarse antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Es para derribar aviones — zona de guerra. Realmente esta ciudad Pedro Juan Caballero …

Steven: [00:26:01] The killing was the beginning of a tit-for-tat that has yet to subside in what is one of the most important drug areas for cocaine coming from Bolivia. Besides, throughout Brazil, fights have broken out between various prison gangs who themselves are vying for many of the same criminal economies and trafficking corridors along the border. Many of these gangs rose to power using the same basic and highly effective formula that the PCC had employed: violent, sometimes even savage, action in order to secure power and social and financial incentives to keep that power. But few can do it as well as the PCC. In the prisons that it dominates, for example, violence between inmates drops. And the group has extended its influence to the street, where in the areas it has hegemony, violence also goes down precipitously. In many of these places, as Ivana told me, the PCC is the de facto police, and no one wants to get in trouble with the police.

Judge Ivana: [00:27:02] Eu tenho um caso que é interessantíssimo: Um indivíduo foi vítima de roubo da sua motocicleta …

Steven: [00:27:08] She said she once had a very interesting case where someone came to her to report that his motorcycle had been stolen.

Judge Ivana: [00:27:15] E eu ouvi esse indivíduo no processo …

Steven: [00:27:17] A few days later, the same guy returned to our office and told her he no longer wanted to get the authorities to investigate.

Judge Ivana: [00:27:24] Ele disse para mim, “Doutora eu não quero mais o processo!”

Steven: [00:27:28] “What happened?” she asked.

Judge Ivana: [00:27:29] “Já recebi a minha moto de volta.”

Steven: [00:27:32] To which she responded that he had gotten his motorcycle back from the local PCC leader.

Judge Ivana: [00:27:37] E meu amigo, eu não quero nem saber o que aconteceu com quem furtou.

Steven: [00:27:41] “I don’t want to know what happened to the person who stole it,” Ivana said. Still, resolving crime is only one part of the work the PCC does to keep the population on their side. The PCC also works as a preventative police.

Judge Ivana: [00:27:57] Qualquer moça, às 11 horas da noite, ninguém, ninguém mexe com elas.

Steven: [00:28:03] Ivana says that in some of the areas they control, women can walk around late into the night without any fear. It’s part of the social contract they’ve created with Brazilian society, and Ivana calls the PCC a parallel state.

Judge Ivana: [00:28:19] Ele concorre com o Estado o tempo inteiro.

Steven: [00:28:21] Where the state is absent, she said, that’s where the criminals are. They are where the people are going hungry, don’t have hospitals, don’t have security. She added that in some poor areas, especially those in big cities like São Paulo, the PCC has the respect and the support of those who live there.

Judge Ivana: [00:28:42] Ele tem o respeito da comunidade, ele ajuda financeiramente a comunidade.

Steven: [00:28:46] “It’s incredible,” she said.

Judge Ivana: [00:28:48] É incrível isso.

Steven: [00:28:55] But what may be more incredible is that after 30 years as a judge, in which she’s seen tragedies like the murder of her friend and colleague Judge Machado, and after 25 years of watching the PCC go from a handful of small-time jailhouse kidnappers and bank robbers to the largest criminal group in the hemisphere, she still believes in justice. While many in Brazil, as well as throughout the region, push for hard line strategies in the face of such challenges, she says that these strategies are not the solutions.

Judge Ivana: [00:29:31] Matar preso e prender não vai acabar nunca com a violência.

Steven: [00:29:35] “Killing them, locking them all up, is not going to solve the violence,” she said.

Judge Ivana: [00:29:43] Se fosse assim tava fácil, fecha os presídios e constrói cemitérios, né.

Steven: [00:29:44] “If it was so easy, then let’s just close the prisons and build cemeteries,” she added.

Judge Ivana: [00:29:51] O desafio não é tão simples. O desafio é maior.

Steven: [00:29:53] “Our challenge is much greater,” Ivanna said. “We have to teach people to be different. That we can all be different. I think that’s what’s needed.”

Judge Ivana: [00:30:04] É ensinar para um cidadão que ele pode ser diferente, que ele pode se sustentar, que ele tem a chance de ser melhor. Eu acho que é isso que falta.

Steven: [00:30:28] This show is a co-production of InSight Crime and La No Ficción. This episode was produced and written by me, Steven Dudley, with a special thanks to Judge Ivana David. Our editors are Elisa Roldán and Thomas Uprimny. Fact-checking by Christopher Newton. Our sound designer is Valentina Fonseca and our graphic designer, Isabella Soto.

InSight Crime is a non-profit organization based in Medellín, Colombia and Washington DC. Our teams go inside prisons, jails, courthouses, police stations, military barracks and even judge’s private quarters, to find out why and how organized crime affects the lives of millions of people across the Americas.

If you think these stories are important, consider making a donation. Every little bit helps and will go directly to reporting these types of stories.

We’ll be back in a couple of weeks with a story about a former guerrilla soldier who died in prison after trying to forge a truce between El Salvador’s vicious gangs. See you next time.

Did you enjoy this episode?

We want our content to remain free. Please consider donating to support our work. Every little bit helps.

In-Depth

Some of the most notorious gangs in Latin America got their start in prisons. They have since become the base from which they can coordinate criminal activities; pay bribes to police, politicians, judges, and prosecutors; and launch full-on, sophisticated assaults on rivals and the state.

These types of operations have become all too familiar in the Americas, from the United States to Colombia, Bolivia, Venezuela, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. At InSight Crime, we’ve tracked criminal dynamics in all of these places, and we’ve found they all have something in common: some of the most important leaders are in jail and often the most powerful criminal groups run their operations from their prison cells.

Nowhere is this more true than in Brazil, and perhaps no one knows this better than Judge Ivana David, who has been working in the Brazilian judicial system for over 30 years. For the fifth episode of our podcast, we spoke to her about the rise of the PCC, Primeiro Comando da Capital, or the First Capital Command, from a handful of prison kidnappers and bank robbers to the most powerful gang in the southern hemisphere.