Demented Society

The US-Mexico border and two demented worlds.

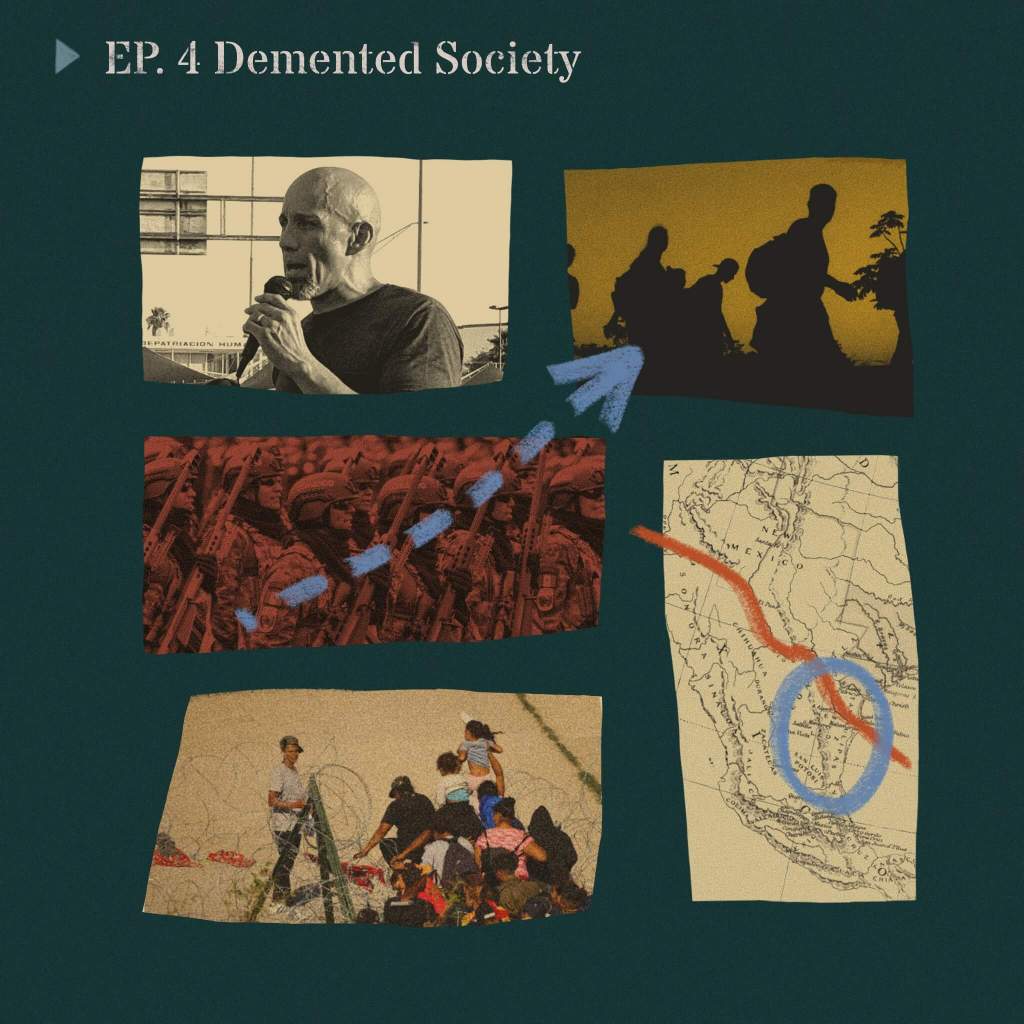

Abraham Barberi is a walking paradox. He is from Mexico but lives in the United States. He does missionary work but plays guitar in a death metal band. He is a Baptist pastor but advocates for migrants and asylum seekers. This is the story of how he navigates these contradictions in Matamoros, the birthplace of Mexico’s Gulf Cartel and one of the country’s most dangerous cities.

Listen on

Transcript

Steven: [00:00:01] It was a breezy, hot summer morning on the eastern part of the United States-Mexico Border.

Matamoros Background Audio: [00:00:09] The migration authorities intercede when they are doing crossing …

Steven: [00:00:10] The sun was already beating down, and we were inserting a metal token into a turnstile to cross from Brownsville, Texas into Matamoros, Tamaulipas, along the Gulf of Mexico. The price of admission was a single dollar.

Parker: [00:00:30] What brought us to Matamoros in May 2023 was the confluence of organized crime and immigration.

Abraham: [00:00:38] What I can tell you is that the cartel is in control.

Parker: [00:00:40] In the last few years, what was the provenance of small, almost mom-and-pop migrant smuggling services, run by people popularly known as coyotes or polleros, has come under the wing of large criminal groups, like the Gulf Cartel.

Abraham: [00:00:56] Matamoros is the house of the Cartel del Golfo. So this is like their strongest city.

Steven: [00:01:03] This was our guide, Abraham Barbary. He is a local pastor and also refers to himself by the Spanish version of his Biblical name, Abrahán. But we’re going to call him Abraham.

Abraham: [00:01:17] ¿Cómo andamos, hermanos?

Parker: [00:01:19] In Matamoros, the Gulf Cartel’s Central Hub, Abraham does what he calls missionary work. What this means in practice is that he helps migrants — thousands of them — as they traverse this dangerous gauntlet. On this day, he was taking us to visit a sprawling migrant camp along the Rio Grande, the famous, and often unpredictable river that separates the United States and Mexico.

Abraham: [00:01:45] Nobody crosses that river without paying the cartel. This is a dangerous town.

Steven: [00:01:56] Welcome to InSight Crime’s Podcast, where we investigate from the ground up to help you understand how organized crime works in the Americas. I’m your host, Steven Dudley, InSight Crime’s Co-Director.

Parker: [00:02:09] And I’m Parker Asmann, an InSight Crime investigator and today’s co-host.

Steven: [00:02:17] In this episode, with the help of Abraham, Parker and I will explore how the mighty Gulf Cartel went from a drug trafficking organization to one that has its hands in everything from human trafficking to migrant smuggling. We’ll also discuss how both US and Mexican immigration policies are helping strengthen already powerful criminal groups and how people like Abraham, with some traditional and some very non-traditional methods, face down the power of organized crime.

Abraham: [00:02:52] They’re smart, man. That’s why they’re called organized crime.

Parker: [00:03:02] Matamoros is a lively city of about 600,000 people. When you look at a map, the point where Steve and I were crossing is shaped like an upside-down V. On one side, the Rio Grande juts north along a boulevard. On the other side, it quickly snakes south along a narrow avenue where the camp was.

As we walked towards the camp, we crossed a small plaza with vendors selling everything from fresh juices to socks, balloons, and classic Mexican sombreros. Military trucks with soldiers riding in the pickup bed drove past and signaled at us not to take pictures of them.

The crowds thickened as we reached the entrance to the camp. In front were rows of houses and two- and three-story buildings. On the other side, down a steep flush riverbed, was the Rio Grande. The United States stood tantalizingly close.

The camp was spread up this elongated patch of land along the river, but was well-organized. There were clearly defined pathways, and rows of tents and other makeshift housing made of pieces of wood and zinc. There were kids running around and playing. There were vegetable and fruit stands, a barber, a place to collect water. Power strips hung from tree limbs, and cellphone charging cords draped the trunks like a weeping willow.

As we walked through the camp with Abraham, he greeted a group of migrants.

Abraham: [00:04:44] Cómo andamos, hermanos? Ayer vino el del agua? Si, vino? Okay.

Steven: [00:04:51] Abraham, has made a name for himself along this part of the border. He is the pastor of a local church, where he services many at-risk youth. He’s also a mainstay at the camp, where he helps migrants with everything from the basics — like food, water, and shelter — to the logistics. When we visited, Abraham was doing his best to help the migrants navigate a shaky cell phone application the US government had just launched to program visa appointments. It was nearly impossible to log into or navigate the app.

Abraham: [00:05:23] En Google esto va a estar la nueva aplicación y me estaban recomendando que el mejor …

Steven: [00:05:28] Abraham is slender and fit. He has a cleanly shaved head and a small well-groomed salt-and-pepper jazz patch on his chin. His mannerisms are deliberate, and his cadence is soft. He has an engaging smile, and he interacts with the migrants with ease.

Abraham: [00:05:46] … and that was because — ¡perdón jefita! …

Steven: [00:05:48] After all, he’s also a migrant.

Abraham: [00:05:50] Entonces este, ahí les encargo cuando venga el del agua. Hoy tiene que venir. Hoy es miércoles, ¿verdad? Okay. ¿Ayer vino? Okay.

Parker: [00:05:58] Life wasn’t easy for Abraham. Both his father and older brother were drug dealers. After his father’s death, Abraham moved from Cuernavaca in central Mexico to live with some relatives on the country’s Pacific coast.

A few years later, he and his mother moved to the Houston area, where he eventually started drinking, doing drugs, and engaging in petty crimes at a young age. In the United States, he found himself caught between two worlds.

[00:06:30] Cumbia music plays.

Parker: [00:06:33] While other Mexican teens were listening to cumbia and norteña music, Abraham was drawn towards a different kind of music: rock and roll.

[00:06:43] Rock and roll music plays.

Abraham: [00:06:52] One day, one of my cousins introduced me to Judas Priest, and I was like, “Oh my God!” And then Scorpions, and I was like, “This is awesome.”

Parker: [00:07:00] Eventually the Scorpions gave way to Black Sabbath, which gave way to Metallica, Anthrax, and a love for fast heavy metal.

Abraham: [00:07:10] You know, I’m playing my guitar and I met another guy, he played the guitar and the other guy played the drums, and the next thing you know, we’re jamming out. And they started a journey of me playing in different bands. I played in several bands, mostly heavy metal, death metal, speed metal, thrash metal.

Parker: [00:07:28] Before he found God, Abraham struggled in the United States. Like most immigrants at that time, he lived in the poorest part of Houston and as he started playing in bands, alcohol, marijuana, and harder drugs followed. And soon, so did trouble.

His drug use was what first led him to Matamoros. He traveled regularly from Houston to the border city to buy marijuana, and then cocaine. Soon he was selling drugs, and eventually, he started transporting small quantities from the border back to Houston. This led him to jail. He spent just a few months in a Houston prison cell, thanks to a good lawyer who got him probation.

Steven: [00:08:11] Abraham was in trouble. He was drinking heavily, using drugs, and he owed people money in Matamoros. But one day he remembered a small Christian Church in Houston where somebody had invited him once. In a later telephone interview, he told us he was hesitant because he’d grown up Catholic, but he went anyway.

Abraham: [00:08:30] I was watching the worship band, and they were really talented, so that got my attention. And eventually the preacher came, and I was going to leave. I was like, nah, I don’t want to listen to this bible-thumping preacher. You know, he’s gonna tell me that I’m a sinner and all that, and I just wanted to leave.

Steven: [00:08:45] At the pulpit was Keith Richards. Abraham, never forgot the name of that preacher, obviously, because he shared the name of the Rolling Stones lead guitarist, who was famous for his own public struggles with alcohol and drugs. But Abraham would remember much more about that fateful day.

Abraham: [00:09:03] When I went to that little church, I remember they were singing songs that were very different than the Catholic Church, and the lyrics were very moving, I would say. I guess that’s what I needed to hear that night. One of the songs was talking about, you know, “God renew me, give me a new heart. I’m tired of being the way I am.” I thought, “That’s exactly what I need, a new heart.”

Steven: [00:09:23] Abraham never looked back. He said that if God loved him, he wanted to love him back by changing his bad habits.

Abraham: [00:09:31] That was what changed my heart, you know, that God loved me unconditionally, and he was willing to take me the way I was. And I was a terrible person, my brother, I mean, had done some terrible things.

Steven: [00:09:43] He stopped playing in bands and started going to church regularly. Then he started seriously studying religion. He and his wife started engaging in missionary work all along the US-Mexico border. This included Matamoros, where he provided translation services to a friend who was working at a small church. He also began preaching regularly whenever he came to Matamoros.

Abraham: [00:10:05] And ever since, I just — my heart stayed here, and I kept coming back and coming back. And then it got to a point where I was coming back very often — every month, every two months, just to do missionary work.

Steven: [00:10:18] In 2009, in part due to the drug trafficking related violence along the border, Abraham and his family moved to the Matamoros area to do missionary work full-time. He felt it was his duty to come back to the place where he once got into trouble.

But by this time, the city had changed. It was not the same low-level violence and criminality he saw as a teenager. But even amidst what was a tumultuous tit-for-tat between the Gulf Cartel and their onetime bodyguards, known as the Zetas, Abraham and his wife founded One Mission Ministries.

This eventually included opening several churches across Mexico in Central and South America as well as a hip hop urban ministry they called Esencia Urbana, or Urban Essence, which works with at-risk youth in Matamoros.

Christian rap: [00:11:08] Hey, what’s up? En español ¿qué pasó? Enemigo al tiró, el MC Poncho ya llegó.

Steven: [00:11:13] Despite not being a hip-hop Fan, Abraham found the youth loved connecting to religion via rap music. It wasn’t just about singing and praising God, but taking power away from the Gulf Cartel. By showing young people a different way of life, the Gulf Cartel had fewer potential recruits. It’s a dangerous proposition. One song Abraham helped produced is aptly called “Medio Loco,” or “Half Crazy.” In the video on YouTube, two rappers take turns praising Jesus Christ.

Christian rap: [00:11:46] Je-su-cris-to

Steven: [00:11:50] And calling for others to join their movement.

Christian rap: [00:11:52] Reino de los cielos. Mi misión: si estás tirado, declaro en el nombre de Jesús que te levantas del suelo. Traigo bendición para el niño, el adulto …

Steven: [00:12:00] Back at the camp, Abraham tells us that because of this work, his nickname around Matamoros is el pastor de los raperos, the pastor of the rappers.

Abraham: [00:12:13] And eventually, there was like a little revival thing. One of them became a Christian, and then another one became a Christian, and then another one became a Christian.

Christian rap: [00:12:19] De mi se rieron. Es que junto con mi señor, mi vida pasada ...

Parker: [00:12:22] Abraham has helped a lot of young people in Matamoros. One of them, Samuel, is now serving as an assistant pastor and helping them with his missionary work.

Abraham: [00:12:33] He used to work for the cartel, he was a sicario.

Parker: [00:12:35] A sicario, or hitman. But now he is not only Abraham’s right-hand man in his ministry, but a talented rapper. Through rap music, Abraham has helped many like Samuel avoid being ensnared by the way of life sold by crime groups like the Gulf Cartel.

Abraham: [00:12:51] I never thought it was gonna work.

Parker: [00:12:53] Abraham had good reason to be skeptical. The Gulf Cartel had exerted power in Matamoros for decades, long before he ever started coming to the border city. It had its tentacles in everything and was expanding.

Steven: [00:13:10] There are many milestones for US immigration policy, but when it comes to understanding organized crime in its confluence with immigration, the most important came in the mid 1990s.

US government representative: [00:13:21] Mr. President, Mr. Speaker.

Steven: [00:13:24] In January 1995, US President Bill Clinton gave his State of the Union address. In the months prior, facing a fierce conservative political backlash, Clinton had re-engineered immigration enforcement.

President Bill Clinton: [00:13:39] All Americans, not only in the states most heavily affected, but in every place in this country, are rightly disturbed by the large numbers of illegal aliens entering our country. That’s why our administration has moved aggressively to secure our borders more by hiring a record number of new border guards, by deporting twice as many criminal aliens as ever before.

Steven: [00:13:59] The policy was called “prevention through deterrence.”

President Bill Clinton: [00:14:03] We are a nation of immigrants, but we are also a nation of laws. It is wrong and ultimately self-defeating for a nation of immigrants to permit the kind of abuse of our immigration laws we have seen in recent years, and we must do more to stop it.

Steven: [00:14:20] It was very simple: The US government believed that the harder you made it to cross the US-Mexico border, the fewer would try to cross. However, the policy didn’t work, evidenced by the fact that there has been a steady increase in migration over the last 30 years. In 2023, for example, US authorities saw a record number of what they call “migrant encounters,” government-speak for when the border patrol or the coast guard detains an undocumented migrant.

What’s more, faced with increased enforcement, migrants began to travel through treacherous territory. The list of ways to die went up exponentially: desert, mountains, rivers, cold, heat, thirst, exhaustion, injury, infection, and, of course, criminal organizations. Migrants were moving in greater numbers through the same corridors where these organizations were moving drugs and extorting other criminal groups.

Parker: [00:15:26] The approach had several unintended consequences. By making it harder to cross the border, a booming black market for clandestine border crossings emerged. And recognizing the scale of profits to be made, traditional drug trafficking groups like the Gulf Cartel, which is the dominant group in Matamoros, became more involved in migrant smuggling. Over time, they began demanding fees from coyotes. And if migrants were traveling without coyotes, they could be kidnapped and held for ransom. Or worse, they could be forced to work for the cartels as foot soldiers, or maids, or sex slaves.

Newscast 1: [00:16:04] The Gulf Cartel is among the most powerful criminal organizations in the entire country.

One of the reasons that human smuggling is so enticing to drug cartels is that, unlike drugs, humans come back — oftentimes get deported right back where they started and often very willing to shell out that money again. So, it’s a cycle.

Steven: [00:16:22] When the Gulf Cartel and the Zetas split around 2010, it got even worse. The Zetas would intercept migrants en route, charging them an additional ransom or simply murdering them. In August 2010, for instance, the Zetas massacred 72 migrants, just over 100 kilometers south of Matamoros.

Newscast 2: [00:16:42] Investigators believe the migrants were kidnapped by the drug gang and then killed after refusing to work for the cartel.

Steven: [00:16:48] The US-Mexico border is just one part of what has become a deadly gauntlet. We spoke with several migrants in the camp, most of them Venezuelans, who’d spent more than two months traveling across eight countries. Along the way, they’d been extorted by corrupt police and migration officials and threatened and abused by organized crime groups, paramilitaries, guerillas, and smugglers. Still, they all agreed on one thing: Mexico was the worst part.

Abraham: [00:17:17] Ahorita a las diez — ya pasó, ¿verdad? Ya, es la última vez que utilizan la aplicación.

Parker: [00:17:23] Back at the camp in Matamoros, Abraham tried to explain the new cell phone app that the US government had launched.

Abraham: [00:17:30] Va a salir la nueva aplicación. Esa ya no la van a utilizar.

Parker: [00:17:34] It wasn’t easy. The app kept crashing, or after the migrants would enter their information and hit submit, the app would just freeze, showing that spinning wheel of dots on the phone going endlessly in a circle. Everyone was exasperated, trying their hardest to do things the right way.

Migrant 1: [00:17:52] O sea, hago todo programado. De nuevo, de cero, todo, todo, todo.

Abraham: [00:17:55] Con esa aplicación, es la nueva.

Parker: [00:17:57] Because undocumented migrants have two ways to get into the United States: go through the US system or try to go around it.

Migrant 2: [00:18:05] Pero me gustaría que Dios me abra las oportunidades.

Parker: [00:18:08] When we were there, going through the US system meant hoping and praying they could get an appointment via the clunky cell phone app.

Migrant 2: [00:18:15] Donde yo pueda trabajar y ganar bien para ayudar a mi familia.

Parker: [00:18:19] One Venezuelan migrant we met had already gotten lucky and would later have his appointment in Texas. He made it all the way to Chicago, where he is going through the asylum process.

Migrant 2: [00:18:30] También que me guste. Que gane bien.

Parker: [00:18:32] But the vast majority of them would languish for months waiting for that little wheel on their phone to stop spinning.

Migrant 2: [00:18:39] Entonces, este bueno, vamos a ver cómo nos vamos allí.

Steven: [00:18:42] Their second option was to enter without documents. There were obviously numerous obstacles to this plan. The most obvious stood right in front of us: the Rio Grande. Another Venezuelan migrant who had made it across told us that he would have drowned were it not for a fellow migrant who snagged him by his shirt as the current was dragging him under. Still, they cross by the dozens.

As we walked over the international bridge to the migrant camp, we could see them making their way. Some were waist-deep in the river, trudging through the mud and leafy banks. Others were neck-deep.

On the other side, the US government awaited. In Texas, that meant both state and federal authorities, some of which were carrying heavy weaponry. If the migrants made it across the river, then through the razor-sharp Concertina wire, they would most likely be captured by the phalanx of border enforcement. It was desperate.

And from there, it could get worse. They could go to federal prison, where gangs often prey on them. They could be sent to another border crossing and return to Mexico, where criminal groups could prey on them again. They could also be put on an airplane and sent home, where they would have to start the journey all over again. Or they could be sent back to this camp in Matamoros, where things could also get complicated.

Newscast 3: [00:20:15] En Matamoros, Tamaulipas, quemaron intencionalmente 25 casas donde se refugiaban migrantes de diferentes nacionalidades en un campamento.

Parker: [00:20:22] Just days before our visit, a group of men burned several dozen tents and other makeshift housing.

Newscast 4: [00:20:28] Muestra de la desesperación, un incendio en algunas carpas de un campamento improvisado en Matamoros, Tamaulipas.

Parker: [00:20:34] Some of the migrants scrambled to put out the fire, but the fear it sparked spread much further and deeper into the camp.

Newscast 4: [00:20:41] Apenas con botellas de agua podían apagar el fuego para tratar de salvar lo poco que tienen.

Parker: [00:20:47] There were several theories about who started the fire, but all of them came back to one overriding theme: the control the Gulf Cartel exerts over the camp. As we toured the area along the Rio Grande. I talked to Abraham about the incident.

Abraham: [00:21:05] Well, there were a couple of families living over there, and they crossed the river and didn’t pay the cartel. So the cartel said if you do that again, this is what’s gonna happen to you.

Parker: [00:21:15] So it’s a warning.

Abraham: [00:21:15] It’s a warning, yeah. Everybody knows you get a pay to go across the river.

Parker: [00:21:20] And are they keeping records? Do they have ledgers of people that have paid? Is there a clave system here? Like there is …

Abraham: [00:21:27] Yeah, there’s a clave like anywhere else. Yeah.

Parker: [00:21:29] A clave, literally it means a key or a code. The way it works is similar to a fee. Anyone who wants to cross needs to pay the Gulf Cartel for a clave. How much that costs seems to fluctuate, but when we were there, the migrants said it could range from a couple hundred dollars to a few hundred dollars per person. But it’s not just about migration.

Abraham: [00:21:51] Anything illegal that you do, then they come and want a cut from you.

Parker: [00:21:55] Contraband, drug peddling, human trafficking — sometimes the cartel itself controls these businesses. Other times they collect from them.

Abraham: [00:22:05] If you do everything legal, you do it the right way, you’re paying taxes, they leave you alone. But as soon as you do anything that is illegal, then they come.

Parker: [00:22:14] In some paradoxical way, the cartel provides order to the chaos. For example, Abraham said that some people in Matamoros pose as lawyers and promise visas or asylum, then abscond with the money desperate migrants give to them. The Gulf Cartel reprimands those would-be lawyers as well. They also keep order at the camp, using the fear of violence to eliminate theft, fighting, and domestic disputes.

Abraham: [00:22:41] You’d be surprised about the cartel here. They have some kind of ethics, ethical code. And one of them is, you don’t do anything to children and women. For example, if a husband beats up his wife, and they call the cartel, they beat him up for doing that.

Parker: [00:22:55] It can be easy to miss at times. But if you look closely, you’ll see small groups of young men monitoring the activity in the camp. They look no more than 25 years old, and they walk around and use small hand-held walkie-talkies to report back to their superiors. And although they are not armed, they are easy to spot: they wear clean clothes and have nice sneakers.

Steven: [00:23:23] The camp was noticeably clean for a squalid neighborhood of some 2,000 people living in tents and sleeping on cardboard. There was music, but it wasn’t too loud. There was no one drinking alcohol in the open or noticeably drunk, and people appeared to be leaving their valuables and food in the open.

Abraham: [00:23:43] I was telling you that, he asked me who was the security situation here — the cartel. They come here and say: no, fighting, no drugs, no alcohol, no beating women, and you’re okay. That happens, then we’ll come, and you’ll pay for it. So yeah, the police won’t come here. The army won’t come here. The INM, the first time, this past two weeks they’ve been here.

Steven: [00:24:05] The INM, that’s Mexico’s immigration service. It was another illustration of how public policy decisions were facilitating organized crime’s rise. Despite Matamoros being one of the most militarized border crossings in the world, the Mexican authorities, the police, the army, the immigration services had barely visited the migrant camp. The Mexican authorities had effectively outsourced the organization and security of the camp to the Gulf Cartel.

When we spoke to migrants, they were constantly looking around, scanning the area to see who was watching, listening. But they were relaxed, in the sense that they were not worried about getting their things stolen or being dragged into drunken fights or sexually assaulted. In other words, there appeared to be no obvious security problems within the camp. This dichotomy is strange for someone coming from the outside. We’re often taught that crime is analogous to disorder, chaos, when in fact, sometimes, the opposite is true. Sometimes, it is the only order people can rely on.

Abraham: [00:25:32] Esa es la nueva aplicación que van a utilizar ahora.

Parker: [00:25:35] At the camp, Abraham talks with yet another migrant about whether they’ve downloaded the new US government cell phone application. The two go back and forth as if they’re talking about some new video game they’re trying to play.

Abraham: [00:25:50] Acaba de salir la nueva aplicación para que descarguen.

Parker: [00:25:55] The situation would be comical were it not so tragic. Where the Mexican government leaves the migrants to the whims of organized criminal groups like the Gulf Cartel, the US government tries to bandage it up with a phone application.

Abraham: [00:26:08] Búscate en la Google Store.

Migrant 4: [00:26:11] ¿En Google Store tengo que buscarlo?

Parker: [00:26:12] And more often than not, it’s up to people like Abraham to make it work on the ground.

Abraham: [00:26:17] De cero con eso.

Migrant 4: [00:26:18] O sea, hago todo programado de nuevo. De cero, todo, todo.

Abraham: [00:26:22] Si, con esa aplicación. Es la nueva. Es la que van a utilizar. A ver si te sale. Okay.

Parker: [00:26:27] He is used to playing these types of thankless roles, bandaging up flawed policies and protecting vulnerable populations. As a migrant himself, he is committed to this work.

Still, it’s tricky and dangerous. On the one side, the US government’s increasingly militaristic approach to migration has forced migrants into ever more dangerous corridors. And on the other side, the Gulf Cartel and other large criminal groups along the border are taking advantage of these policies to expand their criminal portfolios and control over the migrants.

Abraham: [00:27:09] Let me just put it this way. You talk to a Venezuelan and you ask them — or any asylum seeker, but right now, cause it’s mostly Venezuelans — you ask them, “What was the most dangerous part of the journey?” They say, “Well, you know the Darién Gap was bad. Central America was bad. Crossing Mexico was the most dangerous part because of the cartels.”

Steven: [00:27:35] It can be dispiriting. But Abraham, through music and the gospel, continues his missionary work in addition to the hip-hop ministry that helps extract sicarios from the cartel’s grip, Abraham has returned to his first love, heavy metal.

Abraham: [00:27:52] I’ve been playing in a heavy metal band since I was 14, and I’m 55, and it’s just — it’s in my veins, you know? I like that stuff.

Steven: [00:28:00] After some 15 years without playing in a band, he picked up his guitar again and connected with the local metal scene in Matamoros.

Abraham: [00:28:08] Playing death core corner is a good way to relax — for me.

Steven: [00:28:12] With some of his devout friends, Abraham formed a religious death core band called “My Place Was Taken.” It’s a far cry from rap music, but it maintained the religious theme.

Parker: [00:28:27] One of the songs is called “Sociedad Demente.” It translates as “Demented Society.” It’s difficult to understand because the singer vocalizes in a guttural, almost satanic role. But beneath the raspy, gruff staccato is a song that chronicles the desperation of a mother who has found her son’s body cut into pieces.

As he jams to the music in a video posted on YouTube, Abraham stands in a power stance: legs bent, slight bow of the head, his guitar across his chest. The song shakes you, as the singer screams over and over again, “Sociedad demente. Sociedad demente.”

Steven: [00:29:40] Maybe Abraham and his bandmates are right, that ours is a demented society. Or maybe there is hope and a better path forward, we just have to look elsewhere to find it.

This show is a co-production of InSight Crime and La No Ficción. This episode was produced and written by me, Steven Dudley, with help from Parker Asmann.

A special thanks to Abraham for being our guide at the migrant camp. You can find the link to his band’s song, Sociedad Demente, in the description of this episode.

Our editors are Elisa Roldán y Tomás Uprimny. Our sound designer is Valentina Fonseca, and our graphic designer Isabella Soto.

At InSight Crime, we investigate how organized crime preys on the most vulnerable in our societies. If you think these stories are important, consider making a donation. Every little bit helps and will go directly to reporting these types of stories.

Christian rap: [00:30:59] Oh, comunidades urbanas …

Steven: [00:31:03] We’ll be back in a couple of weeks with a story about a female judge who fights the most powerful criminal organization in the Americas, Brazil’s First Capital Command.

Christian rap: [00:31:15] Chaparrito y negrito poniendo en alto el nombre de Jesucristo. Por si no escuchaste, te lo repito. Por si no escuchaste …

Steven: [00:31:22] In the meantime, get ready for your Spanish lesson.

Christian rap: [00:31:27] Hey, what’s up? En español: que pasó? Enemigo al tiró, el MC Poncho ya llegó. Chaparrito y negrito poniendo en alto el nombre de Jesucristo. Por si no escuchaste te lo repito. Por si no escuchaste.

Did you enjoy this episode?

We want our content to remain free. Please consider donating to support our work. Every little bit helps.

In-Depth

The Gulf Cartel is one of Mexico’s oldest and most powerful organized crime groups. For decades, it has trafficked drugs and other contraband across the US-Mexico border from its home base in Matamoros, Tamaulipas. But in recent years, restrictive immigration policies have forced thousands of migrants to wait in this same border region as they contemplate how to reach the United States.

In response, Mexico’s powerful organized crime groups have become increasingly involved in migrant smuggling. The business has gone from intimate “mom-and-pop” operations to possibly a multibillion-dollar industry controlled in large part by predatory crime groups like the Gulf Cartel. What was once a more manageable journey — though still fraught with serious abuses and dangers — has metastasized into a gauntlet controlled by vast networks of smugglers, corrupt government officials, and transnational criminal networks.

We have covered the unintended consequences of US immigration policy extensively. In a 2023 investigation, we analyzed the many ways organized crime groups have taken advantage of these policies, including by extorting migrants and kidnapping them for ransom. Official corruption has also expanded as the United States increasingly relies on countries like Mexico to enforce these policies.

Profile

The Gulf Cartel

The Gulf Cartel is one of the oldest and most powerful of Mexico’s criminal groups but has lost territory and influence in recent years to its rivals, including its former enforcer wing, the Zetas.

Episode Credits

This show is a co-production of InSight Crime and La No Ficción.

Produced and written by Steven Dudley with the help of Parker Asmann

Edited by Tomas Uprimny and Elisa Roldán

Reporters: Steven Dudley and Parker Asmann

Sound Design by Valentina Fonseca

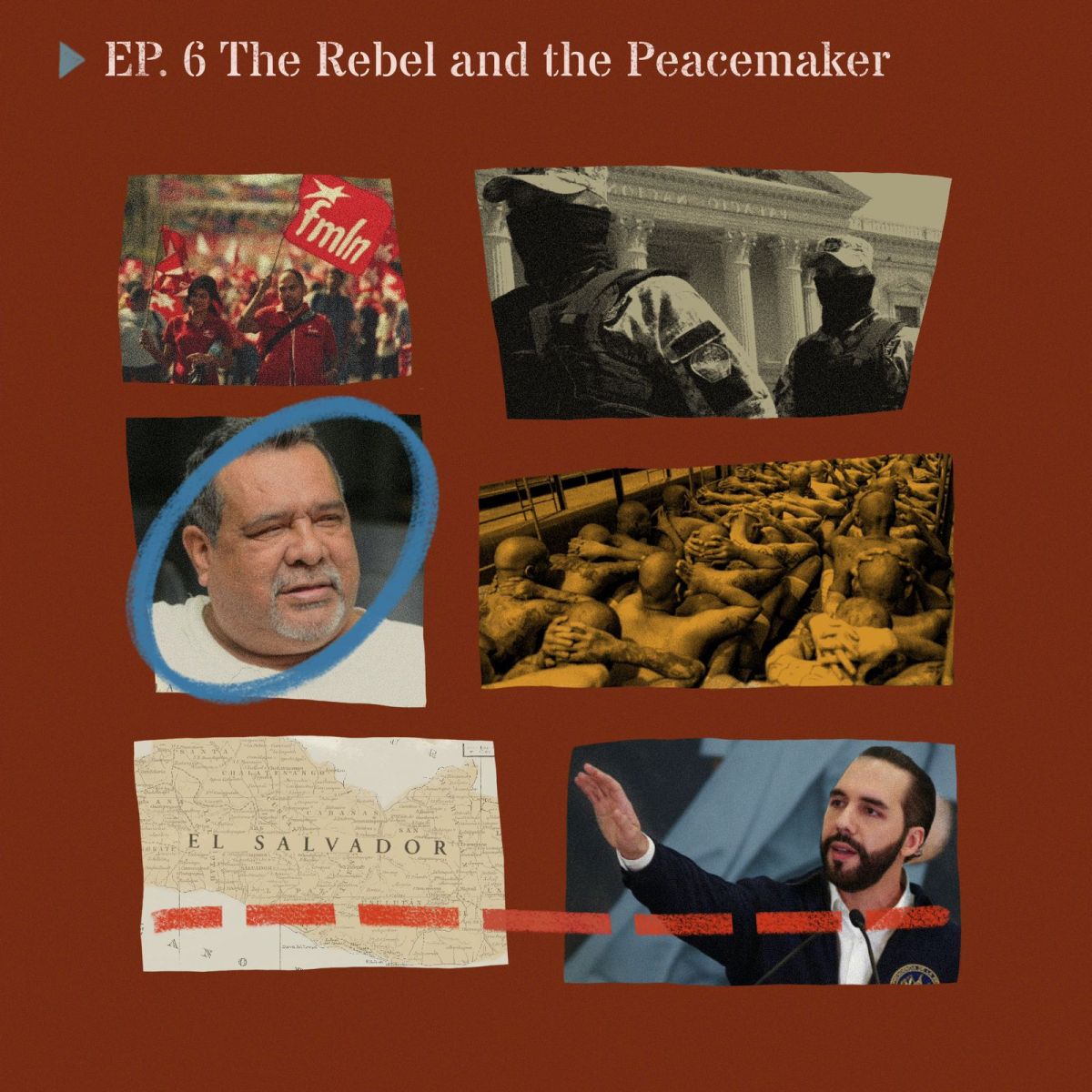

Cover Illustration by Isabella Soto

Thanks to Abraham for sharing his story with us

Explore Our Investigations