The Rebel and the Peacemaker

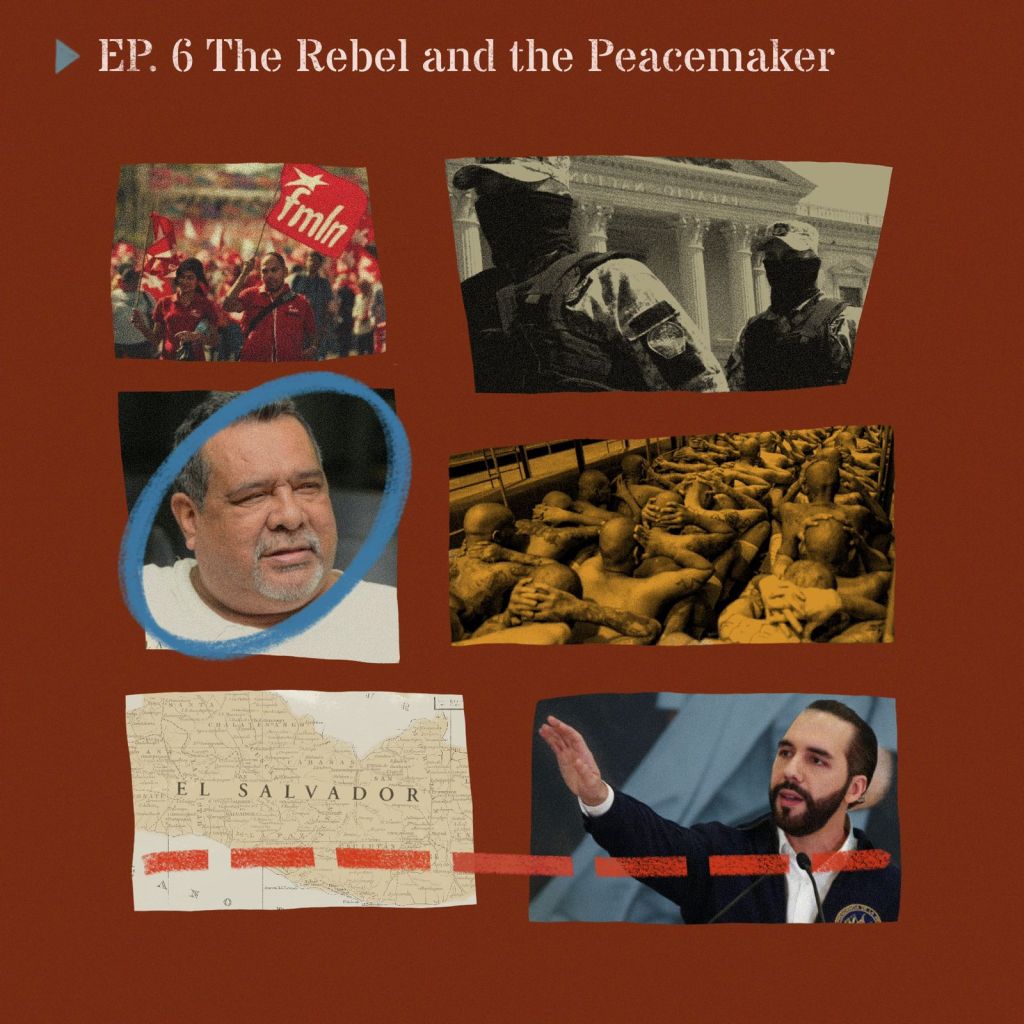

Raul Mijango, the rebel turned congressman turned gang mediator turned inmate who personified what has since become a lost cause in El Salvador: negotiating with street gangs.

In our last episode of this season, we explore the incredible life of Raúl Mijango, the rebel turned congressman turned gang mediator turned inmate who personified what has since become a lost cause in El Salvador: negotiating with street gangs. And, ironically, he may have been one of the first victims of a controversial, hard line strategy that has since led to the incarceration of tens of thousands of Salvadorans.

Listen on

Transcript

Steven: [00:00:01] In 2018, I went to a courthouse in San Salvador, the capital city of El Salvador. There was a case that had caught my interest, one that I thought had huge implications for the country’s future. One of the men on trial that day was Raúl Mijango. Mijango was a one-time rebel turned congressman turned gang mediator. He had been a central figure in the politics of the country and the ethical debate about an existential issue facing El Salvador: how to deal with street gangs.

True to his guerrilla roots, Mijango was of the mind that the gangs themselves had to be part of the solution, and he had dedicated the last few years of his life to that cause. But others disagreed. So much so, they vilified him after he’d brokered a temporary ceasefire between the main street gangs and the Attorney General’s Office charged him with extortion in a case involving the truce. That was the trial myself and a journalist named César Fagoaga were there to see.

Mijango had been in jail for a few months, and the day we went to talk to him, his hands and feet were cuffed. He was dressed in white shorts and a white T-shirt and wearing plastic Crocs. During a break, César and I got a chance to speak with him. The courtroom was about the size of a small classroom. Two prison guards led Mijango to one side, and he sat down on a row of plastic seats fastened to a long black metal bar. We nudged our way closer and sat down, flanking him on two adjacent seats. His face, which used to be a radiant glow of brown behind a soft white Fu Manchu, had become pale. He was, he told us in not so many words, dying.

Mijango: [00:01:56] Ya estoy viejo. Me funciona solo el 30% de mis riñones …

Steven: [00:02:02] I’m old he said to us. Only 30% of my kidneys work. I have severe diabetes, thyroid problems, ulcers in my stomach and lately, because of the diabetes, I’ve lost 60% of my sight.

Mijango: [00:02:17] Se me ha bajado casi el 60% de la visión.

Steven: [00:02:21] It was sad. What Mijango thought was going to be his crowning achievement — making possible an almost impossible gang truce — had turned into his funeral.

Mijango: [00:02:32] Yo siempre he dicho, quiero a este país. No sé si el país me quiere a mí.

Steven: [00:02:37] I’ve always said “I love this country,” he added. “I’m just not sure this country loves me.”

Welcome to InSight Crime’s podcast, where we take you to the furthest reaches of the Americas to help you understand how organized crime works from the ground up. I’m your host, Steven Dudley, InSight Crime’s co-director.

In this episode, with the help of César Fagoaga, we explore the incredible life of Raúl Mijango, the rebel turned congressman turned gang mediator turned inmate who personified what has since become a lost cause in El Salvador: negotiating with street gangs and ironically may have been one of the first victims of a controversial hard line strategy that has since led to the incarceration of tens of thousands of Salvadorans.

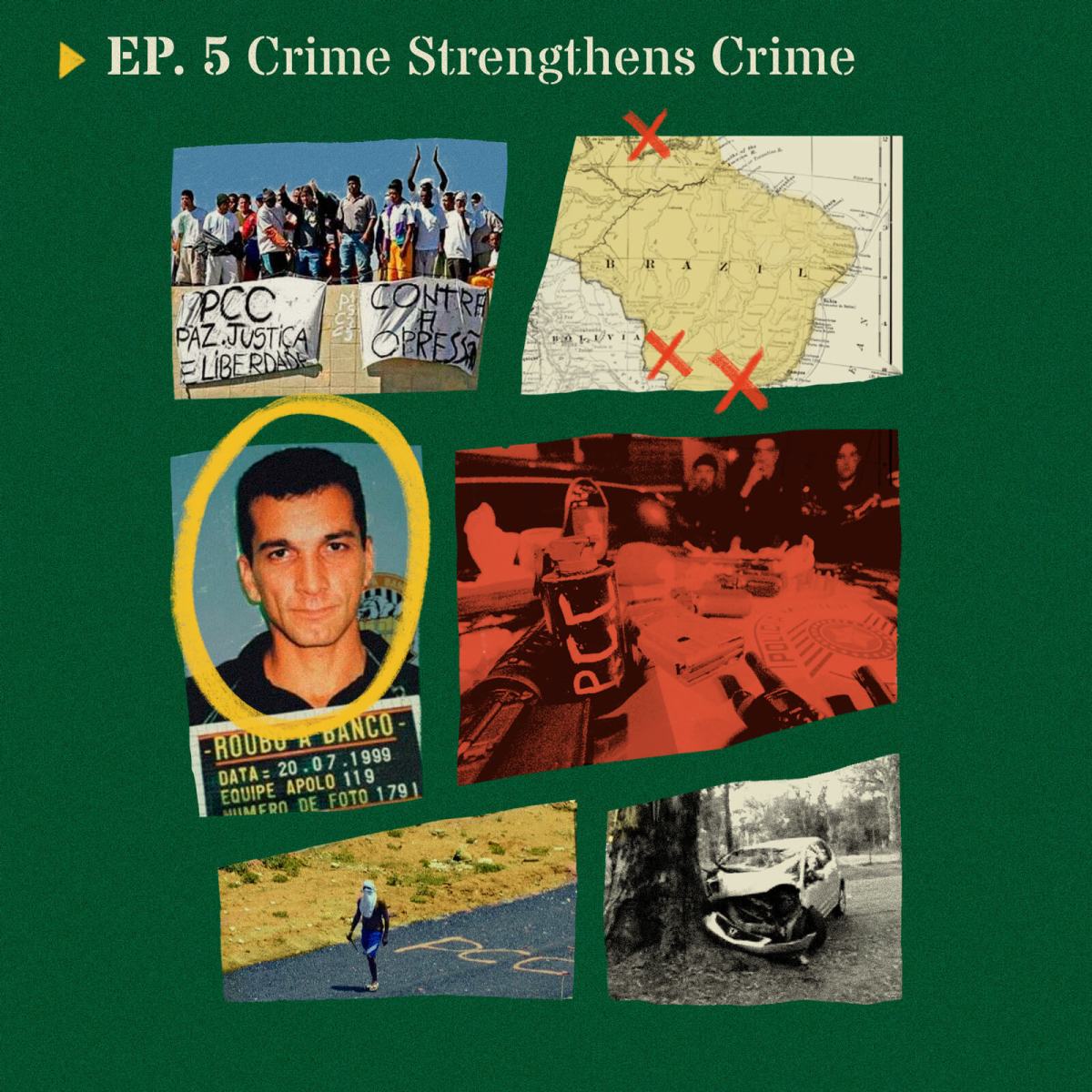

From the beginning, Mario Alberto Mijango, who would later take on the nom de guerre Raúl, was a dreamer and an idealist. Born in a rural town, he joined the leftist guerrillas at a young age. And by the 1980s, he was a mid-level field commander of one of the factions of what was known as the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional or FMLN, the rebel umbrella group.

He was known for his stamina and his stealth operations. He trained in Nicaragua and Cuba, and carried an AK47 assault rifle he claimed Fidel Castro had given to him personally.

More than anything, he was a fierce combatant. In one battle, he commanded an ambush that killed 30 government soldiers. In the late 1990s, after the ruthless civil war, the FMLN became a political party by the same name, and Raúl became a congressman but later fought with the leadership of the FMLN and eventually left the party.

Raúl irked them in many ways. He was always more pragmatic social democrat than dogmatic Marxist, so it wasn’t surprising that he quickly made connections to other political parties, including one led by a military official named David Munguía Payés. As it turns out it was Munguía Payés who Raúl had ambushed on the battlefield, killing 30 of his soldiers. And although their joint political efforts failed at the ballot box, the two forged a relationship that would eventually spawn the gang truce.

In the meantime, the gang problem was getting worse. Around the time the FMLN was signing a peace agreement and becoming a political party, gang members were being deported from the United States to El Salvador by the thousands. Many of them were from Los Angeles’ most notorious gangs, the Mara Salvatrucha or MS13 and the Barrio 18 or 18th Street. They had formed during El Salvador’s civil war, when hundreds of thousands fled to places like L.A. After they were deported back, it wasn’t long before these gangs usurped the local Salvadoran gangs and began systematically extorting the country’s bus companies, small stores, mechanics, and other businesses.

To deal with them, the government jailed suspected gang members en masse and what was termed mano dura, or iron fist policies. But eventually the gangs turned this strategy on its head and took control of the prisons. They started to mobilize from inside and later outside of jail. Murders skyrocketed. In 2010, El Salvador’s homicide rate was one of the highest in the world. Most of the victims were gang members themselves, as the MS13 and 18th Street squared off in a brutal tit-for-tat.

By then, Munguía Payés was security minister, and he had hired Raúl Mijango as a consultant for the ministry. Raúl had been arrested, although never convicted, for some petty crimes in between his stints in government. Inside jail, he’d met some gang leaders. Now, outside of jail, he had a radical proposal for the guy who started out as his enemy, became his political ally, and now was his new boss, Munguía Payés.

Mijango: [00:07:24] Hay una mezcla de medias verdades y medias mentiras.

Steven: [00:07:27] When César and I met with Mijango during his trial, he told us his goal in negotiating with the gangs was simple: reduce the violence.

Mijango: [00:07:36] Qué es lo que nos propusimos? Reducir violencia en el país.

Steven: [00:07:40] How did they do this? The government transferred 30 leaders of the MS13 and the 18th Street to medium security prisons, where they could reclaim their control over the rank and file members. Almost overnight, the homicide rate dropped from about 14 murders a day to about five per day.

Mijango: [00:08:00] Y eso permitió parar la espiral de violencia.

Steven: [00:08:09] The drop was extraordinary. So extraordinary, Raúl told us, that others began to contact him and the other gang mediator working with him, Bishop Fabio Colindres, the military chaplain of the Catholic Church in El Salvador.

Mijango: [00:08:25] Algunos que se sentían afectados de otro tipo de delitos comenzaron a buscarnos para que le ayudaran.

Steven: [00:08:31] The callers were from some of the country’s most important industries, such as the transport sector and the food distribution sector. He said they were interested in lowering extortion and robberies.

Mijango: [00:08:43] Qué posibilidades hay de que nos ayuden?

Steven: [00:08:45] “What are the chances you can help me?” the callers asked.

Mijango: [00:08:49] Y en este caso en particular, esa empresa me llamó a mí para plantearme lo siguiente.

Steven: [00:08:55] In one case in particular, he said the owners of a food distribution company at the time called him and told him that if he didn’t intervene, 400 employees would be out of a job because of the extortion of the gangs, which they said was costing them about $15,000 per month and was about to put them out of business.

This was not just any case. It was the case for which Raúl was being tried when we spoke with him.

Raúl would eventually broker a telephone call between the gangs and the company, during which they negotiated a new type of arrangement. Instead of $15,000 in cash, the gangs would get $6,000 worth of what the indictment says were “pre-cooked rice, beans, cooking oil, Pampers and other goods.” It was a win-win, Raúl thought. The company paid less, and its employees were safe to distribute their goods. The gang lowered its extortion rates but could make money selling the goods themselves at the open air marketplaces across El Salvador.

However, the indictment against Raúl tells a slightly different story.

It says it was Raúl who called the company to offer his services. And it says that Raúl benefited economically from the subsequent deal.

Raúl denied these accusations. He says he simply put the sides together to talk.

Mijango: [00:10:26] Igual lo hice con empresarios de transporte que llegaron y me decían, mire …

Steven: [00:10:32] He also said he and the other mediator, Bishop Colindres, mediated between the bus companies and the gangs as well, where they negotiated lower extortion rates, and that they were on the verge of getting the gangs to eliminate extortion altogether for small-time vendors and storefronts. The government, he said, should have assumed this role. But it didn’t. So he and Colindres did.

It was a risky move, but one that he thought he had to take. Although violence was down, public support of the truce was waning because extortion had continued. And he thought these actions could save the agreement.

I should stop here and say a couple of things about the truce. Although security minister Munguía Payés was involved, and the government had transferred gang leaders between prisons, the truce was not officially sanctioned by the government. And although President Mauricio Funes acknowledged the truce publicly, he also distanced himself from it, putting the onus on the negotiators and his security minister. There were, in other words, no rules whatsoever about what Mijango could and could not do. This lack of clarity confused me, so I asked Raúl if anyone had authorized him to intervene in extortion cases.

Steven: [00:11:57] Una pregunta: Usted en algún momento se comunicó con el gobierno?

He was adamant. “The government knew exactly what I was doing,” he said. He added that his office had a direct line to a police intelligence unit. Even the Attorney General’s Office knew, Mijango said.

Mijango: [00:12:18] El Estado por supuesto que sabía todo.

Steven: [00:12:20] The government knew everything.

In my reporting about the truce, both before and after our meeting with Raúl, I corroborated Raúl’s account. The truce I found was something akin to what has been called in the United States street outreach or violence interruption. In the US, there are variations of this model, but all of them depend on current and ex-gang members that tried to interrupt the chains of retribution between warring gangs. In our interview with Raúl, I asked him if they had interrupters.

Mijango: [00:13:00] A esos nosotros le llamamos no interruptores, sino que le llamamos facilitadores.

Steven: [00:13:05] He said they had 70 people who they called peace facilitators instead of interrupters, but it was basically the same model.

Mijango: [00:13:15] Es una labor de apagafuegos terrible ¿verdad?

Steven: [00:13:18] These guys were like firemen, Raúl said. And there were constant fires every hour of every day.

Mijango: [00:13:26] Sostener un proceso de esas magnitudes no es fácil.

Steven: [00:13:31] To carry out a process of this magnitude is not an easy task, he added.

Although Raúl did not mention it to us, I chronicled instances when both the MS13 and 18th Street leaders killed their own members for not adhering to the truce. Maintaining the peace, it appeared, required violence.

The truce had other problems as well. Depending on who you asked, the payment to the gangs included not just transfers out of maximum security prisons, but bringing plasma screen TVs into the jails, giving the gangs control over the commissaries, providing gang leaders with monthly salaries, and opening the penitentiary doors to prostitutes, liquor, marijuana, and other party favors.

Although homicides were still down, the truce was under fire, and as the country entered a new round of presidential elections in 2014, the top candidates distanced themselves publicly from the agreement. But behind the scenes, both the country’s largest political parties negotiated with the gangs, promising them they would continue some form of the truce if they won. In return, the gangs provided votes. The winner was a hardliner from the wing of the FMLN who had expelled Raúl from the party in the early 2000s, and despite their private campaign promises, the new administration quickly abandoned the strategy of talking to the gangs and launched an offensive against them which included, it appeared, the use of death squads who would shoot unarmed suspected gang members after they were captured. The truce was officially over.

The gangs began to target the government, ambushing police, Killing off-duty officers, assassinating prison guards, and detonating homemade explosives. Fighting also broke out between the gangs as they settled long-simmering scores. Homicides reached record levels that made El Salvador the most violent country on the planet not at war.

Newscast 1: [00:16:00] Esta es la única imagen que se tiene hasta ahora de la captura de Raúl Mijango.

Newscast 2: [00:16:05] Allanaron la casa del ex mediador de la Tregua, Raúl Mijango.

Steven: [00:16:09] It was in this context that the Attorney General’s Office filed multiple charges against Raúl and numerous gang leaders for extortion of a food processing company, the same company that he had helped to lower its extortion rate from $15,000 a month to $6,000 in products. By the time we sat down with him in that courtroom, Raúl had come full circle, going from being a guerrilla commander to being prosecuted by its political offspring.

Steven: [00:16:42] Usted en ese sentido, se siente traicionado?

So I asked him if he felt betrayed by his former FMLN comrades.

Mijango: [00:16:50] No, jamás. Me siento defraudado.

Steven: [00:16:53] No, he said, I feel defrauded. Defrauded because I believed in the government, in the country, in the idea of peace. Defrauded because the government decided that fighting the gangs with death squads was better than negotiating, that it was better to jail people en masse than to negotiate. They are, and I’m paraphrasing him now, a bunch of hypocrites. Mijango also said he thought that some of them wanted to keep the fighting going for their own economic interests.

Mijango: [00:17:25] La violencia en este país es uno de los negocios más lucrativos que hay.

Steven: [00:17:30] Violence is one of the most lucrative businesses there is, he said. And many of those with power don’t want to end that business.

Mijango: [00:17:38] Estas esposas que yo tengo en las manos ahorita son la expresión de eso.

Steven: [00:17:43] “These handcuffs that you see on my wrists right now,” Mijango said. “Well, they’re just a result of that hypocrisy.”

Mijango: [00:17:50] Sí tengo una lectura.

Steven: [00:17:52] “Still, I have a theory about my incarceration,” Mijango told me and César.

Mijango: [00:17:57] Mi lectura es que esto es parte de toda una acción de persecución política.

Steven: [00:18:02] “It’s political persecution,” he said. There was some merit to this argument. Mijango was, after all, one of two gang mediators. The other, Bishop Colindres, had not been charged, nor would he be.

César: [00:18:18] Porque cree que al señor Colindres nunca lo detuvieron?

Steven: [00:18:21] “Why did they jail you and not Bishop Colindres?” César asked.

Mijango: [00:18:24] Monseñor Colindres y todos los del gobierno que estuvieron involucrados en esto tienen más retaguardias políticas, diplomáticas, etcétera que yo.

Steven: [00:18:34] “People like Colindres have political support, diplomatic support,” he said. “I don’t. I’m the skinniest dog on this ship.”

Mijango: [00:18:44] Soy como el perro más flaco de todo este volado.

Newscast 3: [00:18:52] A 13 años, con cuatro meses de prisión, fue condenado Raúl Mijango por el delito de extorsión a una empresa arrocera.

Steven: [00:19:02] In October 2018, a few weeks after we saw him, Raúl Mijango was found guilty and sentenced to 13 years in prison for extortion in the case of the food distribution company. The verdict was sad but not surprising.

Newscast 4: [00:19:17] Mijango expresó que apelará la decisión del Juzgado Especializado de Sentencia V de San Salvador.

Mijango: [00:19:22] Mal paga el diablo, más bien le ayuda, y aquí nosotros lo que hicimos es intentar ayudar a la víctima.

Steven: [00:19:31] By then, El Salvador was in another round of presidential elections. Among the candidates was Nayib Bukele. Fit, neatly dressed, and sporting a tightly quaffed beard, Bukele was the picture of a new generation of millennial politicians. Like Raúl, Bukele had broken with the FMLN. But unlike Raúl, he had used the break to catapult himself into the national spotlight.

Bukele: [00:20:04] Esta batalla no empezo en el 2012.

Steven: [00:20:08] Bukele had started in public relations before becoming the mayor of a small town. Then in 2015, he ran and won the mayoral race in the country’s capital, San Salvador. It wasn’t long after Bukele took power in San Salvador that my colleague César got a tip from one of his sources that the brand-new mayor was negotiating with street gangs.

César: [00:20:30] Yo creo que el primer tip que tuvimos sobre eso fue cuando Bukele era alcalde de San Salvador.

Steven: [00:20:36] César told me when I talked to him later that the tip didn’t surprise him. Mayors in San Salvador and other mayors around the country had long dealt with gangs. It was impossible not to.

César: [00:20:50] Bukele inició un proceso de reordenamiento de algunas cuadras del centro histórico.

Steven: [00:20:56] In Bukele’s case, he had negotiated with the gangs that were controlling the city’s historic center. The center was home to the country’s largest open air market. There, as many as 40,000 unlicensed street vendors hawked everything from concrete to knockoff tennis shoes to cell phone cases. The gangs made money by extorting each of these vendors, something in the range of a dollar a day. In other words, they could make $40,000 a day just from these vendors alone. Bukele wanted to move the vendors to more formal markets that city hall was developing, but the gangs resisted. So Bukele sent an emissary to negotiate with the gang leaders.

César: [00:21:39] Al final, Bukele tuvo a personas que tuvieron un papel muy similar al que tuvo Mijango.

Steven: [00:21:45] César said the emissary played a role similar to that of Mijango, in that he placated the gangs. In this case, he made sure the transfer of vendors to formal marketplaces did not affect the gangs’ ability to extort the same number of vendors. It was, he said, the first red flag with regards to Bukele.

César: [00:22:05] La primera campanada de alerta.

Steven: [00:22:08] The pact, however, was not public. It would only become public later because of our investigations and others into Bukele. But in the interim, Bukele looked like a political savant. His efforts led to many vendors moving to formal marketplaces and a renaissance of the historic center, where new bars and restaurants opened up for the first time in years.

César: [00:22:31] Él entendió que la alcaldía de San Salvador era el trampolín necesario para llegar a la presidencia.

Steven: [00:22:36] Bukele used this revitalization project during his time as mayor of San Salvador as a way to launch his presidential campaign, casting himself as someone who could transform difficult, violent areas into a vibrant, economic hubs. The strategy worked. In 2019, Bukele, running as a political outsider, easily won the presidency.

Newscast 5: [00:23:01] Nayib Bukele arrasa en las presidenciales de El Salvador, y se convierte en el presidente más joven de la historia reciente del país.

Steven: [00:23:10] From the beginning, the 37-year-old Bukele pushed the boundaries of power. For example, when Congress refused to authorize a foreign loan for security equipment, he sent the military to storm the legislature and threatened to disband the lawmaking body.

Newscast 6: [00:23:27] Un hecho sin precedentes desde el final de la Guerra Civil en 1992: la entrada de militares y agentes policiales fuertemente armados en el Parlamento obedeciendo órdenes del Presidente Bukele.

Steven: [00:23:39] He also continued to negotiate with gangs. Salvadoran journalists and later InSight Crime investigators spoke with current and former Bukele officials, who told us that the government traded benefits in prisons with a commitment on the part of the gangs to lower homicides. Sound familiar?

César: [00:23:58] La administración Bukele jamás lo reconoció.

Steve: [00:24:02] Again, the pact was never made public, and Bukele has denied any agreement was made at all. But César said there was clear evidence that administration officials had entered prisons on numerous occasions to negotiate the pact. In addition, his administration even released some high-level leaders from jail, all to show their commitment to the secret agreement.

Like the previous truce, homicides dropped, this time to their lowest levels in 20 years. Bukele made everyone believe this drop was due to his anti-gang strategy, which he called the territorial control plan when in reality, it was a product of the secret gang truce that he publicly denied.

Bukele rode this wave of relative calm to another round of electoral victories, this time in the midterm elections of 2021, which gave his party a super majority in congress. He also fired the attorney general after the country’s top prosecutor began investigating him and his cronies for corruption during the pandemic, and he reconfigured the high courts and his security forces, filling important posts with loyalists.

By early 2022, Bukele had consolidated full power. And then in late March, the gangs committed a spate of murders that made it the deadliest weekend since the civil war. Ostensibly, the gangs were protesting something connected to the pact they had made with the president. Theories abounded. An untimely arrest. A murder of a prominent gang member. Failure to pay the gang leaders for their participation in the pact. Whatever it was, Bukele abruptly ended the arrangement.

At his behest, Congress enacted el régimen de excepción, or a state of emergency. El régimen, or the regime as it came to be known, was an unprecedented crackdown. The irony was thick. Bukele had consolidated so much power in part because his pact with gangs had lowered homicide rates, and now he was using that power to destroy those very gangs — even threatening to starve them in the jails.

Press Conference, Bukele: [00:26:34] Ustedes desatan una ola de criminalidad y nosotros quitamos la comida en las cárceles. Les juro por Díos que no comen un arroz — uno.

Steven: [00:26:41] In six months, authorities arrested close to 80,000 people which they claim were members, aspiring members, or collaborators of the gangs. The power of the regime means they can hold these suspects indefinitely without charging them or giving them access to legal assistance. Prosecutors told César and me they couldn’t even get into the prisons. But in one hugely important respect, the strategy worked.

César: [00:27:12] Hay una desarticulación de las pandillas muy evidente.

Steven: [00:27:15] Most gang members were jailed or fled, César said. The gangs were, as he put it, “dismantled,” and the people felt much more safe.

César: [00:27:24] Y en las calles eso se refleja.

Steve: [00:27:27] This was evident when César and I traveled through El Salvador’s streets, speaking to businesses and civilians who’d been victimized by gangs for years. These victims were happy to speak to us in public places, something neither of us had found during previous reporting trips, and the gangs were nowhere to be found.

César: [00:27:47] Ahora sabemos por investigaciones que no todos son pandilleros.

Steven: [00:27:50] Still, César said, thousands of those detained were innocent. They were arrested, he said, because the police had a quota they had to fill.

César: [00:28:00] Pero el costo que se tiene es altísimo, y que creo que la gente en El Salvador todavía no es muy consciente de lo que está pasando.

Steven: [00:28:05] “The regime,” César said, “is not just undermining the rule of law. It’s also making us numb. In two years, the state of emergency has become a permanent feature of Salvadoran life.”

César: [00:28:20] Y se ha convertido en una herramienta de control social.

Steven: [00:28:24] “And now it’s like a form of social control,” he added. Anyone who challenges the regime can be thrown in jail without any recourse.

On August 28, 2023, some 17 months into Bukele’s regime, Raúl Mijango passed away in prison.

Mijango had lived an extraordinary life, but it was as if he and his ideas about how to deal with gangs — not with bullets or mass incarceration, but with truces and by attacking the social roots of the problem — had been buried long before his funeral. At the time of his death, about 1% of El Salvador’s population was in prison, giving it the second-highest prison rate in the world.

César: [00:29:21] Mucha gente piensa que el problema de las pandillas está completamente solucionado.

Steven: [00:29:26] These days, César says no one wants to hear about a gang truce. They think this problem has been solved.

César: [00:29:32] Al menos yo creo que es un problema que está suspendido.

Steven: [00:29:37] For his part, César thinks the gang problem has just been temporarily suspended.

César: [00:29:41] Mucha gente ha comprado el discurso que la única forma de acabar con este problema es un fósforo y gasolina …

Steven: [00:29:49] “The people think that the only way to deal with this problem is with a match and gasoline,” he added.

César: [00:29:55] … Quemarlo todo.

Steve: [00:29:57] “To burn everything down.”

Mijango’s death left a similarly bitter taste in our mouths. The interview César and I did with Raúl was the last time either of us saw him alive. When we left Raúl and the court that day, he thanked us for coming.

Mijango: [00:30:19] Gracias por venir.

Steven: [00:30:21] As we turned to walk away, he seemed moved by our visit. Someone still cared about what he thought, what he had experienced.

Mijango: [00:30:30] Me gusta que haya gente que todavía se acuerda de lo que hicimos.

Steven: [00:30:35] Handcuffed and gaunt, his skin yellowing because of failing kidneys, he was far from the stout rebel soldier who’d once ambushed his rivals on a steep mountain pass. Still, he remained steadfast, telling us that one day the country would realize that they would have to do what he and his team did. That there was no alternative.

Raúl had tested the limits of power, first as a guerrilla, then as a politician, and lastly as a gang mediator. He escaped with his life in the first two battles, but this third battle, the existential one that had tied El Salvador in knots for decades, was too much — even for Raúl.

This show is a co-production of InSight Crime and La No Ficción. This episode was produced and written by me, Steven Dudley, with great help from César Fagoaga. A special thanks to my crack gang investigations team, which includes César, as well as Alex Papadovassilakis, Juan José Martinez d’Aubuisson, Carlos García, and Brian Avelar. Fact-checking on this episode by Christopher Newton and Juliana Manjarrés. Our editors are Elisa Roldán and Thomas Uprimny. Our sound designer is Valentina Fonseca and graphic designer Isabella Soto.

See all our coverage of gangs, gang truces, gang wars, and prison gangs at insightcrime.org.

This was the last episode of our first season of InSight Crime’s podcast. Thank you to La No Ficción. We couldn’t have found a better partner. And thank you to InSight Crimes’ whole reporting, graphics, social media, editors, and administrative teams.

If you want to binge the whole season — and believe me you’ll want to! — you can do it at Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts on. We will take you to meet Bolivia’s courageous volunteer firefighters, a brave Brazilian judge, and Honduras’ female gang members who may defy your expectations, just as they did prison authorities to tragic effect. And we’ll travel from Colombia’s war in the jungle to a Mexico-US border town controlled by the cartel.

At InSight Crime we investigate from the ground up, inspired by the idea that organized crime is not a boring multisyllabic expression, or yet another true crime story from the suburbs, but a matter of life and death for millions of people across the Americas.

As you await our second season, be like Mijango, who despite being in prison, always tried to get the last laugh.

Mijango: [00:33:56] laughter

Steven: [00:34:01] See you next time.

Did you enjoy this episode?

We want our content to remain free. Please consider donating to support our work. Every little bit helps.